CHILDREN worked on the Hulett tea plantation, Kearsney, Stanger, in the early 1900s.

Image: 1860 Heritage Centre

TWENTY-four-year-old Gollapilli Durgy, indentured number 107821, died two years after she arrived as an indentured worker on board the Pongola from Madras in October 1904. The report of her death shows that she died at the Avoca Central Hospital on February 5, 1906, having suffered from complications that arose from severe dysentery.

Durgy arrived with two children, a 7-year-old boy named Nagamma, indentured number 107822, and a 3-year-old female child, indentured number 107823, strangely named Nagamma as well. The family were indentured to the Natal Ltd, Mt Edgecombe, Verulam Sugar.

In 1909, three years after Durgy had passed away, her children were apprenticed to a Mr AM Morel of Mt Edgecombe. Both children’s names appeared on a Form of Contract in Apprenticing Destitute Children.

The form indicated that the Protector of Indian Immigrants, James A Polkinghorne,

signed the form on behalf of the children to be employed as domestic servants until they were 16 years of age, when they would be entitled to a free pass to seek other forms of employment wherever they wished.

As apprentices, they were to be provided with suitable and sufficient food, washing, lodging and be paid two shillings each month. During this time of serving their apprenticeship, half their monthly wages would be paid into the Natal Government Savings Bank to be given to the children on completion of their apprenticeship on the date stipulated in the form.

Reading against the grain of the archival Form of Contract in Apprenticing Destitute Children document, we can deduce that orphaned and destitute children were part of the system of

indenture from arrival to their employment placement, and were subsequently duty-bound and enslaved to a contract without volition.

In this instance, Durgy’s children were officially re-indentured on November 30, 1909, three years after she had passed away in 1906.

A TEA estate at Kearsney, in the early 1900s.

Image: 1860 Heritage Centre

What was the legal status of the children during the three years after their mother passed? Who took care of the children during this time? Why was their Form of Apprenticeship signed three years after their mother had died? Was the Form of Contract in Apprenticing Destitute Children an administrative functionary of the system of indenture to hide the horror of recruiting and holding children to work as adults in growing the colonial economy? Or was this an act of kindness on the part of the Morels in “adopting” Durgy’s children?

Another case of the lingering psychological impact of indenture on children was disturbingly illustrated in the sad tale of 9-year-old Goyadin Mangal, indentured number 126109.

Goyadin and his 1-year-old sister, Raj Kuaria, were orphaned when their mother died on the voyage of the Pongola to Natal from Calcutta in October 1906. Both children were apprenticed as destitute children to Charles J Battle in Kearsney. Four years later, in 1910, when Goyadin was 13 years of age, he was apprenticed for a second time to a Mr A Ireland as a domestic servant, with his apprenticeship to end when he turned 16 on October 29, 1913.

The correspondence that followed in the archival files on Goyadin showed a letter from the Deputy Protector, dated October 30, 1912, requesting that the Protector of Indian Immigrants grant Goyadin a pass well before his 16th birthday. The letter further revealed that Mr A Ireland and Goyadin mutually wished to cancel the contract of apprenticeship.

It was stated that: “The boy has given his employer an amount of trouble, deserting, thieving, etc, and has been in gaol and whipped twice.”

The Deputy Protector proceeded to give Goyadin a pass for 10 days pending hearing from the Protector of Indian Immigrants, stating that “he is not suitable to be given to anyone else as a house servant. He is now 15 years of age and I (the Deputy Protector) think a pass might be given to him”.

CHILDREN as young as 10 worked on the Hulett tea plantation at Kearsney, north of Durban,1900.

Image: SS Singh Collection

Goyadin was twice apprenticed from the age of 9 to 13. His apprenticeship showed the inner workings of the system of indenture in managing orphaned children. Goyadin’s case revealed the harsh reality of the life of children having to endure being whipped and jailed for deserting their employers, and how their lives were entangled in a colonial system that only sought the provision of their labour while denying their humanity.

Beyond the Form of Contract in Apprenticing Destitute Children, other documents made up the employment and use of children in the system of indenture.

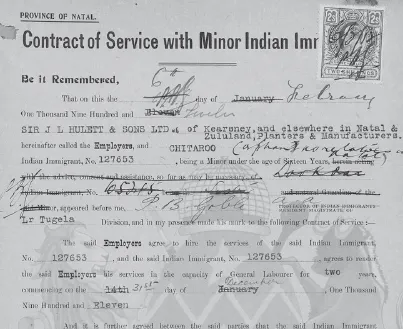

Sir Hulett and Sons Ltd of Kearsney in the North Coast of Natal strikingly had hundreds of Contracts of Service with Minor Indian Immigrants listed in their employment registers of indentured Indians.

The Kearsney Tea estates notoriously preferred the nimble hands of children and women to pick the finest leaves for tea harvesting on their tea estate.

Chitaroo, indentured no. 127653, an orphan with no relatives in Natal, was signed on behalf of Resident Magistrate PB Gobal to work as a general labourer for Hulett’s for two years from 1912.

In the two years that Chitaroo was to be employed, he was to earn 3 shillings per month for the first year, and 4 shillings per month for the second year, until he turned 16 years, when he was entitled to a free pass.

CONTRACT of Service with Minor Indian Immigrants for Chitaroo, indenture number 127653.

Image: Pietermaritzburg Archives Repository, Family Search

The gap in the years that Chitaroo was formally contracted points to the illegal use of children hidden within the system of indenture, given that Chitaroo’s mother, 28-year-old Mohari Fali, indentured number 127652, died in 1907, a year after the family of three arrived on board the Umfuli from Calcutta in 1906.

Chitaroo only officially signed a contract of service in 1912 when he was 13 years of age. What was his status in the five years from when his mother had passed away in 1907, when he was 8 years of age, and what happened to his orphaned sister, who was lost to the archive? Was this administrative fulfilment of the Form of Contract in Apprenticing Destitute Children a way of masking the horrors of plantation life, and was this merely a tick-box exercise for the Protector of Indian Immigrants in managing orphaned and destitute children?

In another matter that involved JL Hulett & Sons Ltd, a letter written from their estate to the Protector of Indian Immigrants dated June 11, 1910, disputes the wages of three boys, stating that they “beg to point out that these people are mere boys, we cannot therefore offer them men’s wages, as we pointed out on previous occasion, there is no compulsion in the matter and they (the boys) have expressed their willingness to accept the wages offered and are anxious to re-indenture on this estate”.

The letter goes on to compel the Protector of Indian Immigrants, stating that “if you (the Protector) are unwilling to consent to this, we are not prepared to take them on, on any other terms”.

In a response dated June 15, 1910, the Protector noted that the wages for the 16-year-old boy should have been 16 shillings, the 14-year-old boy at 7 shillings, and the 11-year-old at 5 shillings.

The Protector concluded by stating that: “My difficulty has been that it is now proposed to give these Indians less wages than they should have received in the first term of indenture.”

According to eminent scholar of indenture, Brij Vilash Lal, of the 152 184 indentured workers who came to expand the colonial capital of Natal in the 19th and 20th centuries, 13% were children, 62% were men, and 25% were women.

Children were a strong component that made up the system of indenture. In 165 years since the introduction of indentured labour to South Africa and beyond, one poorly-researched topic is the subject of the child and the provision of their labour within the matrix of indenture.

Despite ample evidence of abuse and exploitation of children during the system of indenture, the full extent of this human tragedy is yet to be made known to the world, close to three decades into the 21st century.

Selvan Naidoo

Image: Supplied

Naidoo is the great-grandson of Camachee, indentured number 3297, and the director of the 1860 Heritage Centre.

** The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of IOL or Independent Media.

Related Topics: