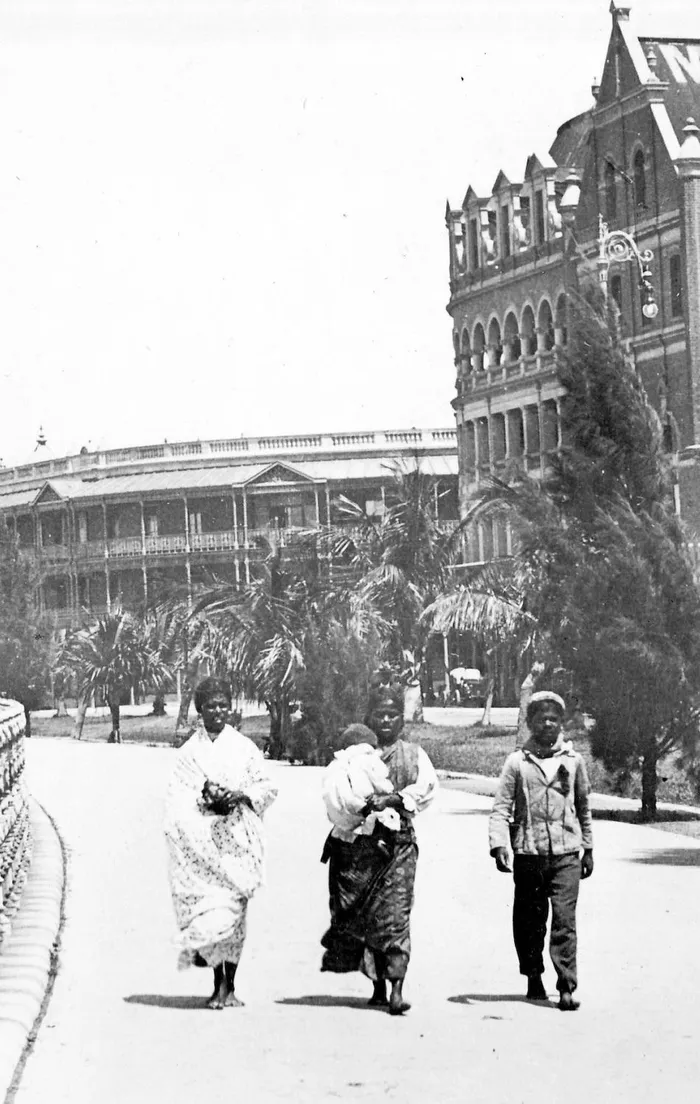

A little girl living on the Tongaat Estates, 1950s.

Image: Tongaati by RTG Watson

ON AUGUST 31, 1908, The Times of Natal, a colonial era publication, reported that a little Indian girl, about 15 years of age, who had made her way from Durban, was found at the Pietermaritzburg railway station by Miss Payne Smith.

The girl named Allamalu was found in a horrible state, suffering from a "disease of the eye and itch" Itch was then the reference for a sexually transmitted venereal disease.

It was discovered that Allamalu, whose parents were deceased, was taken to an Indian hospital where the attendant would not admit her without an order from the magistrate or the district surgeon.

Allamalu was taken to the police station, where she was kept in a cell overnight. In the morning, she was to be taken before the magistrate by the chief constable to receive direction on what was to become of her condition. The constable did his best to admit Allamalu to a hospital, having visited several hospitals, making an application to Grey’s Hospital, the old Indian hospital, also taking her to the new Indian Epidemic Hospital, having pleaded her case before the Corporation Medical Officer and the Chief Clerk of the Court, but to no success.

Child labour, 1957.

Image: Supplied

The chief constable informed the magistrate that there was no place to keep the destitute people, having asked the magistrate to come to some sort of arrangement in placing Allamalu in appropriate care. The government response was that they would erect a special "coloured children’s ward" at Grey’s Hospital for incidents of this nature for the future.

The article appealed to its readers that “every humane-minded person must feel that something should be done; and it is scarcely credible that no provision exists for destitute coloured children”. It concluded by requesting that the magistrate make an order that Allamalu be taken to a suitable hospital and that provision was made (in the future) for the creation of a "coloured children’s ward".

Following the newspaper article, an investigation into the case of Allamalu proceeded. The case file makes up the archival transcripts for a file titled "Nobody’s Child" located in the Indian Immigration files at the Pietermaritzburg Archives Repository.

The first transcript revealed how the magistrate ordered that Allamalu be sent to the Immigration Trust Board Hospital for examination and treatment. The clerk of the court reported the matter to the Protector of Indian Immigrants, stating that the Madras girl of about 15 years of age claimed that her parents had died on the Coast in Natal. Allamalu said that she was put on a train at Nottingham Road, Balgowan, dressed in Mohammedan clothes, talking Hindustani, and was kept by two or three men at different times, suffering badly from the itch.

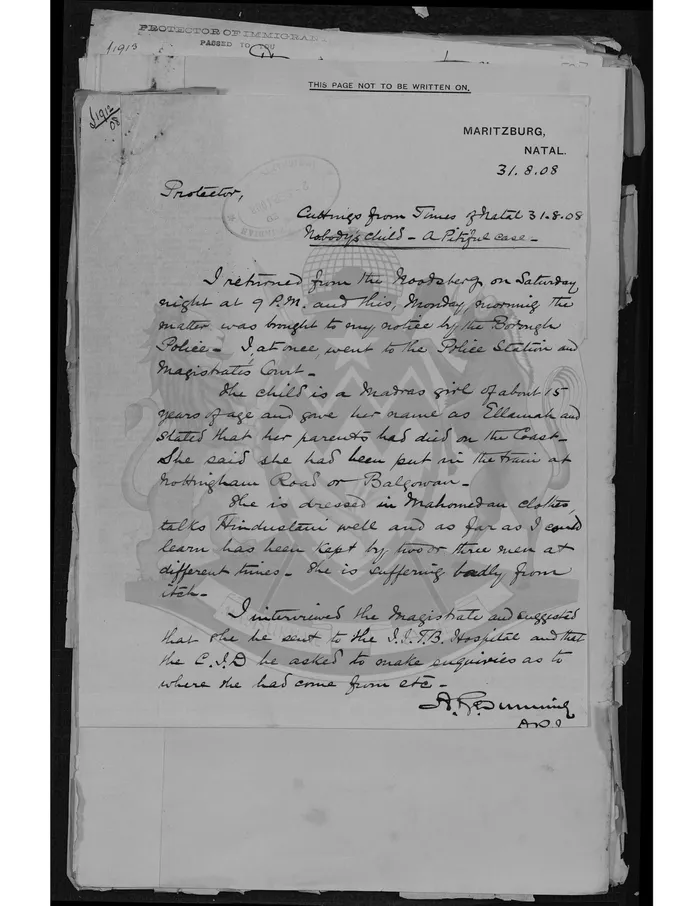

Transcript of Nobody's Child.

Image: Supplied

The next archival transcript outlines a report dated September 9, 1908, from Detective G Brandon of the Criminal Investigation Department of Pietermaritzburg, stating that an Indian woman named Muniamma identified Allamalu as her stepdaughter. Allamalu recognised Muniamma as her "mother". The report went on to state that an Indian constable, Ramasamy, saw Allamalu at the railway station on August 25, who informed Constable Ramasamy that she had come from Howick and was going to see the interpreter of the Indian Court, Mr LM Naidoo.

LM Naidoo stated that Allamalu was brought to his house about four months ago by an Indian named Junai, who was tasked with finding her a master. The court interpreter, then carelessly handed Allamalu over to an Indian named Ryan Ruttie at Nottingham Road, who further stated that the girl, was known to S Singh, and who claimed that the girl had a bad character.

Muniamma explained in her statement to the police that she (Muniamma) was colonial-born to indentured worker Armoogam No 2129, who resided on Mr Cliff’s Brickyard at Pietermaritzburg. Muniamma claimed that she was a child when her parents died, having been looked after by an Indian named Abboyee who lived in Ottawa. When Muniamma grew up, Abboyee arranged for Muniamma to live with an Indian named Chowriemuthu, who was a widower with two children, one of whom was Allamalu, who was then nine years of age.

In the year that followed, Muniamma had two further children with Chowriemuthu. About 10 years later, when Chowriemuthu died, both Allamalu and her biological sister, with their two stepsisters, were in the care of Muniamma for four years. Muniamma claimed she had lots of trouble with both girls, having had to fetch them from various Indian houses. Muniamma then claimed that Allamalu left her and went to Ottawa, only to return about one-and-a-half years ago.

dfdfd

Image: Supplied

Two days later, Allamalu’s elder sister Kanaku arrived to fetch Allamalu, with them both moving to Estcourt, where Kanaku resided with an Indian man. Muniamma claimed that this was the first time, after that incident, that she saw Allamalu in the hospital since she left with Kanaku about one and a half years ago.

Muniamma goes on in her statement, describing that "Allamalu looked weak and miserable because she had not taken care of herself", having come from Estcourt to Pietermaritzburg. At the conclusion of the investigation, a memorandum to the Protector of Indian Immigrants from the Borough Police inspector read that upon the inspector’s last visit to the Immigration Trust Board Hospital, Allamalu seemed to be improving.

He stated that Muniamma was willing to have Allamalu back, but was afraid the “same state of affairs will come about again,” and he suggested that Allamalu be sent to an orphanage where she would be cared for.

“It is a pity, I think, that her condition was not brought to the notice of the authorities four months ago when she was taken to the house of LM Naidoo, the interpreter at Howick, at that time, instead of his handing her over to others."

The incredible archival transcripts titled "Nobody’s Child" give us astonishing insight into the plight of orphaned children in the colony of Natal. It further exposed the commodification of young women, consigning them to a life of no worth or belonging, even from the very same community they expected care and protection from.

Contrastingly, Allamalu’s frailty highlights the dehumanisation of the system of indenture, while also highlighting the goodwill of humanity through the efforts of Miss Smith, who took the time to care for Allamalu in her time of need. One hundred and seventeen years since this incident, and ironically, in the 165th year commemorating the arrival of the first indentured workers on South African shores in 1860, a descendant of indentured ancestry, an emaciated Sharon Pillay, was found in the same condition that Allamalu was found in Pietermaritzburg in 1908.

Sharon, a 41-year-old female, was transported by the provincial ambulance service to Addington Hospital on July 26, 2025, after being picked up from KE Masinga Street in Central Durban, after she was found dazed and disoriented, making it difficult to obtain information about her next of kin. A Facebook post was put up seeking Sharon's family to reunite with their child.

It has taken the month of August with Sharon’s parents or next of kin still not found. Separated by a century, the plight of Sharon and Allamalu must give us ample reason to do more to ensure no body’s child is abandoned.

Selvan Naidoo

Image: File

Selvan Naidoo is the great-grandson of Camachee Camachee no.3297 and Director of the 1860 Heritage Centre.

Related Topics: