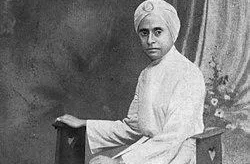

Swami Bhawani Dayal in the 1940s.

Image: Supplied

TO WRITE the biographies of activists rendered citizenless on the margins of empire is incredibly difficult. They often do not make the newspapers of the time, and when they do, it is in ways that caricature or vilify them. But sometimes one gets lucky and a world of diaries or contemporaneous notes is opened up. By working through this information, one gets rare insights into people who spent their lives at the service of the Indian community in South Africa, but of whom we know so little.

One such man is the Natal Indian Congress leader, Swami Bhawani Dayal, (1892-1950) who spent his entire life trying to highlight the challenges faced by local Indians South Africans and this turned him into one of the earliest transnational figures.

In this column, we present the work of United States journalist Negley Farson, who met Dayal on a ship. During this six-day journey, this chance meeting on a roiling ocean reveals the most intimate of details.

Farson toured the African continent in 1939 and met Dayal on a ship from Durban to Dar-es-Salaam. Dayal was on his way to India to rally support against the impending segregationist measures in South Africa.

Farson was the correspondent for the Chicago Daily Sun.

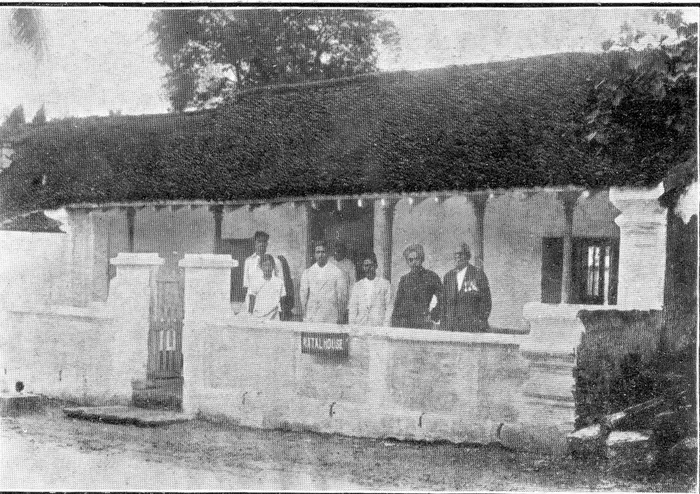

Bhawani Dayal, second from the right, outside ‘Natal House’ in Madras, which cared for repatriates who were in distressed condition,

Image: Supplied

Born in New Jersey, he enrolled for a degree in civil engineering, but his roving spirit saw him drop out and carve a dazzling career as a journalist and author. Farson was in Russia when the Bolshevik Revolution broke out; he covered the 1928 Olympics in Amsterdam; interviewed Gandhi in India and witnessed his arrest in Poona in 1932; and met Hitler and followed his rise to power.

Farson’s African visit saw him visit South West Africa, South Africa, Tanganyika, Kenya, Uganda, the Belgian Congo, French Equatorial Africa, Cameroon and the Gold Coast. He recorded his observations in the evocatively entitled Behind God’s Back.

1939 was the year in which the world teetered on the edge of war. But still there was hope that peace would hold and the Durban port bustled with the ships carrying Empire’s loot. Farson was on his way to Dar-es-Salaam. On board was Dayal. Farson, who had met many global figures, was clearly drawn to the swami and recorded his impressions on the six-day journey.

“Talking with the Swami, I saw that I was in the presence of a serene and noble mind. He was one of the rewards of foreign travel, definitely. He was a Hindu, a holy man, who had given away all his worldly wealth in order to serve mankind. He was the President of the South African Indian Congress. He had written fourteen books on Indian metaphysics and politics. The South Africans had also thought enough of him, his nuisance value, to imprison him for three months; three months’ hard labour, in 1913 - with his wife. Jagrani, and child, Ramdutt—- for organising an Indian strike at Newcastle. And he was deep, unfathomably intelligent, with an easy command of wit and irony. In short, he was one of the most exhilarating boat companions I had met in many voyages.

Negley Farson’s book.

Image: Supplied

“One green sunset, when we were leaning over the rail, watching two rows of Mohammedans on the after-hatch bowing towards Mecca and chanting their prayers, the peaceful scene was broken by an ungodly thumping of Hindu drums and whining stringed instruments from between the decks. He saw the look of appalled annoyance on my face; and the Swami smiled. 'It’s funny ... how unmusical everybody else’s music sounds!'

“In South Africa, it is just the sheer fecundity of the Indian which makes him, in South African eyes, such an ever-growing menace. His multiplicity and his ability to underlive and undersell the white man wherever he comes into competition with him.

“The Swami, in our long moon-lit talks, told me he wanted the Indians’ battle fought in a larger arena - with England as their champion. When we crawled slowly across the muddy waters of Delagoa Bay, with the Lascar leadsmen whining their high cries, a deputation of Indians of Portuguese Africa awaited the Swami on the quay. That night I sat beside him on the platform while he spoke to them of his mission in India. They had hung a wreath of marigolds and coloured field-flowers around his neck, and thrust a bouquet into his hands - as they did to me. And I have seldom felt that I looked more like a corpse prepared for burial.”

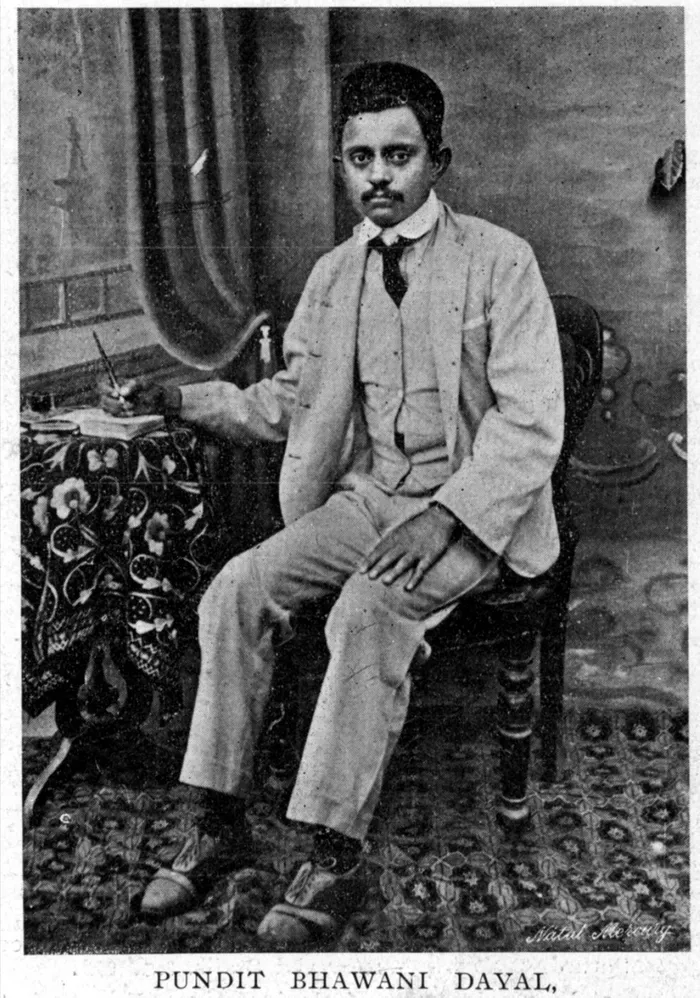

Bhawani Dayal, as photographed on April 17, 1913.

Image: Supplied

Farson found it odd “that the Swami should be going to India to protest against a South African measure".

Dayal told him that the proposed legislation was "a breach of the Smuts-Gandhi Cape Town Agreement" and was "an unbearable insult to the Government of India!"

He would put this blunt question to the Government (of India): “Do you intend to help - or leave alone - the Indians in South Africa?”’

Dayal was confident the bill would create "great agitation in India" and "decide the fate of the British Empire".

Farson countered that the British had enough "trouble on their hands, without putting their fingers into South African politics", a country whose position "within the Commonwealth is one of absolute independence".

Farson writes that Dayal was "unmoved": ‘It is a very grave issue for England, whether she will maintain India within the Empire or satisfy public opinion in South Africa. England can lose her Empire in the handling of the Indian problem in South Africa!”

That was his mission. That was his threat.

At Lorenzo Marques (Maputo), Farson watched Dayal “inflame an eager meeting of Indians of Portuguese East Africa on this embittered and apparently insoluble subject. But what seemed to me so arresting about the little Swami’s speech was not his dark threats to do England in the eye if she didn’t make the South Africans behave more generously to their little brown brothers; it was this attentive audience he was lecturing to.

"In Lourenco Marques, not quite a community of lily-white Europeans, I caught myself wondering why the Indians did not sometimes take it into their heads to draw the colour line against the white man. For certainly these two or three hundred I regarded in this school-room seemed the most respectable, and purest-blooded, people I had encountered in that Portuguese port.

“Back aboard ship I found the captain dutifully doing the honours for some sun-rotted Lourenzo Marques Englishmen. There was a busty brunette who was the epitome of the common English woman who, in the tropic countries, has risen far above her natural level - plenty of servants, and that sort of thing; and her shrivelled little husband, in spite of his monocle, was just a second-rater, whatever he was. She guffawed, when she heard I had been to the Indian ‘do’. 'Oh my, those Wogs! they’re no good to anybody!'

"A Wog, in case you don’t happen to know it, is a pukka sahib's term for any Indian; a Wiley Oriental Gentleman.

“Two spick and span little Jap merchants came off to our ship at Mozambique. The Swami frowned. ‘After 1905, when the Japanese defeated the Russians, we Indians looked up to them as the Saviours of the East'," he said.

"'But not now - now we look upon them as animals. The way the Japanese have treated the Chinese has turned all India against them. We no longer look to them to lead us in our struggle against the West'. And Gandhi? He shook his head. 'No. Gandhi is a fine man, we all love him. I have written his biography. But he has not the modern view. Jawaharlal Nehru, he said, the Harrow and Cambridge graduate, was the strongest man in India. He would lead'.”

Farson’s visit and observations in South Africa, including Durban, led him to conclude: “The threat of the African Indians to use India as a club to browbeat England into taking a hand in African politics is a constant menace to England’s pleasant relations with the South African Government.”

Dayal was one of the few Indian South Africans who lived transnational lives. He was the son of indentured migrants who settled in Germiston in the Transvaal after completing their terms of indenture. He attended the Wesleyan Methodist School and, in 1904, went to study in Bihar in India. He married Jagrani Devi in 1910 and returned to South Africa in 1912 with his wife and son. He was immediately elected President of the Young Men's Indian Association in Germiston, and volunteered in Gandhi’s 1913 passive resistance campaign.

In the face of increased white hostility, Indian South Africans tried to form a national body in the post-World War I period. They had followed developments in India closely and were in contact with Gandhi and nationalist leaders. Dayal represented Indian South Africans at the INC annual meetings in 1921 and 1922. He was part of a South African Indian National Congress that visited Indian in December 1925, where they met Sarojini Naidu, Gandhi, and Viceroy Lord Reading, and attended the Kanpur session of the Indian National Congress. A resolution was passed at the conference condemning the bill as violating the Smuts-Gandhi Agreement and proposing a round table conference.

Dayal was quite incredible in the energy and time he brought to the Indian cause. He was as forthright as he was charming. He could speak softly in conversation but had the oratory skill to move an audience. Among his self-taught skills was his work as a journalist. He published the Dharma Vir newspaper in 1917/18; organised the first and second South African Hindi Literary Conferences in Ladysmith and Pietermaritzburg in 1916 and 1917, and founded the Jagrani Press at Jacobs in Durban in 1922. From 1921 to 1925, he published the Hindi paper. Dayal was the first South African inducted into the Order of the Sannyasi in 1927.

Dayal’s presence in the most important developments of the first four decades of the 20th century was ubiquitous. In 1928, he was involved in the Indian Education Commission in Natal, appointed at the instigation of Sastri. He assisted the Commission leader, KP Kitchlu, and gave evidence before the commission on behalf of the NIC. Hardly taking a breath he returned to India in 1929 and undertook a tour of Calcutta, Uttar Pradesh, and Bihar during 1929 and 1930 to examine the conditions of Indians who repatriated on the basis of the Cape Town Agreement of 1927.

He published a report with B Chaturvedi of the Servants of India Society.

The report, titled "A report on the emigrants repatriated to India under the assisted emigration scheme from South Africa and on the problem of returned emigrants from all the colonies," recorded that most returnees felt ostracised in their villages and were "discontented, and unhappy". He also participated in Gandhi’s Satyagraha campaign in 1930.

When he returned to South Africa, Dayal was elected President of the NIC. In 1939, he was part of the group of activists organising resistance against proposed segregation measures in the Transvaal before returning to India, where he built the Pravasi Bhawan in Adarshnagar, Ajmer, participated in the independence struggle and agitated for the rights of Indians overseas. The Swami Bhawani Dayal Memorial Hospital and Sanatorium was built in Ajmer for TB patients. In Nakasi, Fiji, locals named the Bhawani Dayal High School in his memory.

Dayal’s writings, which include the History of passive resistance in South Africa, My experiences of South Africa, Story of my prison-life, Biography of Mahatma Gandhi, Indians in Transvaal, Natalian Hindu, Vedic religion and Aryan culture, education and cultivator, and The Vedic Prayer, deserve greater circulation.

Dayal Sannyasi, as demonstrated by Farson, was deeply committed to the cause of Indian South Africans. He spoke with rare honesty and developed exceptional verbal and written skills through his engagement in everyday struggles. He was a man who sacrificed everything and expected nothing.

Ponder over this. How many times have you driven past Dayal Road in Clairwood? Have you ever wondered who Dayal was? Why, at the height of white settler racism, did City Hall bend to the wishes of the people of Clairwood in 1932 to name a street after him?

Next time you drive into Clairwood. Remember the Swami who refused to forget the scripture of justice.

Professor Ashwin Desai

Image: File

Professor Goolam Vahed

Image: File

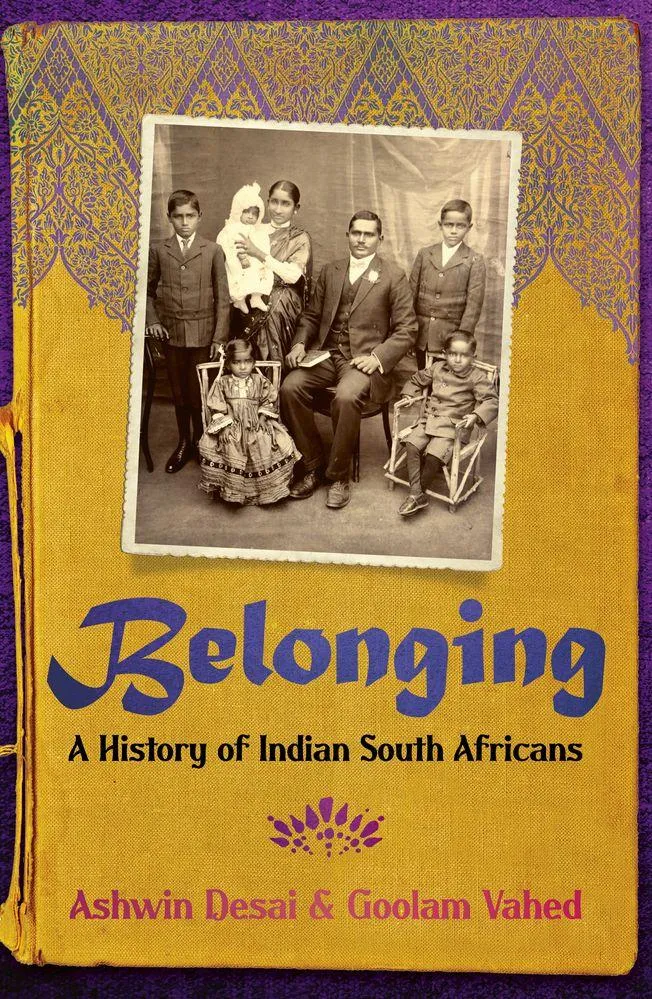

Professor Ashwin Desai and Professor Goolam Vahed's latest book - Belonging: A History of Indian South Africans.

Image: Supplied

Professor Ashwin Desai is the Director of the Centre of Social Change at the University of Johannesburg. Professor Goolam Vahed teaches in the Department of History at the University of KwaZulu-Natal. Their latest book Belonging: A History of Indian South Africans is currently available at Ike’s Books in Florida Road, Durban.

Related Topics: