The life and times of Oliver Tambo

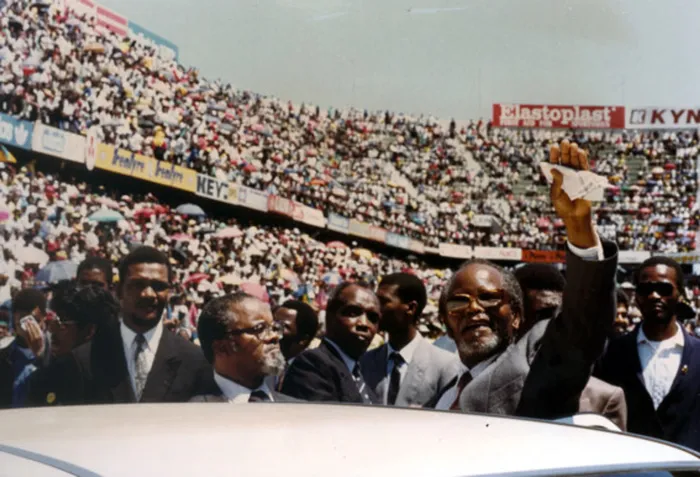

Picture: Patrick Mtolo /INLSA Picture: Patrick Mtolo /INLSA

OLIVER Tambo, leader of the ANC in exile for 30 years, died on April 23, 1993.

Yet his legacy lives on. Comrade OR left us a significant and enduring heritage, one which enhanced our new constitution, contributed to the inclusive and equitable policies of our democratically-elected government, and affirmed the abiding vision of the ANC itself.

The ANC has consistently produced leaders of the highest calibre. But Oliver, thoughtful, wise and warm-hearted was perhaps the most loved.

His simplicity, his nurturing style, his genuine respect for all people seemed to bring out the best in everyone.

Comrade OR’s life was remarkable for the profound influence he had on the ANC during the difficult years of uncertainty, loneliness and homesickness in exile.

During his 50 years of political activity in the ANC, Comrade OR played a significant role in every key moment in the history of the movement, until his death.

Oliver is a founding member and secretary of the ANC Youth League in 1944; the general secretary of the ANC from 1952; the mandated leader of the ANC’s mission in exile 1960; the president of the ANC from 1977 until 1990; then national chairperson until his death.

On an early summer morning on October 17, 1917, in the small village of Kantolo, about 20km from Bizana, Pondoland, a son was born to Mzimeni, son of Tambo, and his third wife, Julia.

Pondoland, known for its green, fertile and available land, had been the last chiefdom in South Africa to remain independent.

The annexation of Pondoland had taken place within Oliver’s parents’ lifetime.

It was an act that completed the process of colonial dispossession of South Africa.

Oliver’s father was acutely conscious of this British assault on Pondoland; the naming of his son "Kaizana" after Britain’s enemy, the Kaizer of Germany during World War I, was making a pointed statement. The Tambo homestead was unusually large, "a big kraal, as distinct from a two-hut home, of which there were many", remembered OR.

The homestead consisted of the paternal grandparents, their three sons and their wives and children.

Oliver’s father, Mzimeni, who was not a Christian, had four wives (though he married his youngest wife, Lena, only after his second wife died in labour).

It is a tribute to Mzimeni that family relationships were harmonious.

The wives had an excellent relationship and the 10 children were very close.

Mzimeni was comfortably off. He owned at least 50 cattle at one time, several fine horses and an ox-wagon.

These resources led to trading and transport opportunities. Mzimeni was not literate – "my father had not seen the inside of a classroom".

His prosperity was largely due to his own enterprise. Shrewd, creative and quick to seize an opening, Mzimeni sought and gained employment as an assistant salesman at the nearby trading store.

This exposure to a more commercial economy taught Mzimeni a number of skills and widened his world.

Two women in OR’s life, his own mother and his father’s third wife, were Christians.

They also opened up new horizons. Oliver’s mother was a sociable and energetic person who could read and write.

She established her home as the local headquarters of the Full Gospel Church. Oliver recalled occasions when there were large, bustling gatherings of worship in his mother’s hut.

Eventually, perhaps because of her influence, Mzimeni himself converted to Christianity and had all his dependants baptised.

In a society where everyone knew almost everyone else, group pressure was a strong form of discipline.

The Amapondo, like many polities in southern Africa, had a consensus approach to decision-making. Between headmen and the community, as well as between chiefs and the people, there was a balance of power.

In his autobiography, Mandela recalled how "at a council meeting, or imbizo, everyone was heard: chief and subject, warrior and medicine man, shopkeeper and farmer, landowner and labourer… It was democracy in its purest form".

The migrant labour system was indeed an integral part of the homestead economy and yet also brought risk and adversity. The health of Wilson, Oliver’s older brother, was ruined when he contracted TB in the compounds of the sugar plantations and had to return home, permanently unfit for strenuous work.

In about 1929, the Tambo family suffered a major tragedy: Oliver’s uncle and his older brother Zakele were killed in an underground fire in the Dannhauser coal mine.

Aside from the heartbreak and personal anguish, the deaths of two healthy and productive members of the homestead was a severe economic blow. Oliver remained deeply attached to his traditional culture.

But thanks to the shrewd insight of his father, OR was also able to learn the skills of the colonisers.

Although Mzimeni was a traditionalist, he also saw the value of western education.

Working in the trading store for many years, Mzimeni had been impressed by two aspects of the white trader: that his learning enabled him to run an independent business and keep its books; and that his relative wealth gave him power and status. As Comrade OR observed:

"People went to him to buy. He had a car, horses – he was a reference point to the community – and he had servants. In general he was a chief in his own right. He certainly was something above the level of ordinary people. It was exactly this difference of levels that my father was targeting, in insisting that his children should go to school."

One day, when Oliver was about 11 years old, he met a lad who was in the debating society of another school.

He and his friends were deeply impressed with the ease with which this youngster spoke English. That experience changed Oliver’s attitude to education. He had discovered in himself a love of discussion and debate and English seemed to be the key to skills, independence and power.

Not long afterwards, Oliver was given the opportunity, through a family friend, to enrol at the missionary school at Flagstaff, called Holy Cross.

By this time, Oliver’s father did not have money to pay the fees. But Oliver was so anxious to stay, that the school itself managed to find two kind English sisters who sent the sum of ten pounds a year for Oliver’s schooling.

From then onwards, Oliver never looked back.

Oliver finished his schooling at St Peter’s in Johannesburg, a school which exposed him for the first time to boys from other provinces, who spoke other African languages, and also to fast-talking city youngsters.

The black press reported the achievement with great pride that this excellent scholar was from the Transkei and the eastern Cape assembly of chiefs, the Bhunga, granted Oliver a bursary of 30 pounds a year to study at Fort Hare.

Oliver decided to study science.

Three years later, Oliver graduated with a BSc degree in physics and maths.

The following year he enrolled for a diploma in higher education. OR had a calm and quiet disposition, but he made an impact on his lecturers and his fellow students.

He was deeply religious, yet he was also an intellectual. His future friend, partner and comrade, Nelson Mandela, recalled his first impressions of Oliver:

“I became a member of the Students Christian Association and taught Bible classes on Sundays in neighbouring villages.

“One of my comrades on these expeditions was a serious young science scholar whom I had met on the soccer field.

"He came from Pondoland in the Transkei and his name was Oliver Tambo.

“From the start, I saw that Oliver’s intelligence was diamond-edged; be was a keen debater and did not accept the platitudes that so many of us automatically subscribed to.”

● This article first appeared on sahistory.org.za

For the full version, go to http://www.sahistory.org.za/archive/his-life-and-legacy-oliver-tambo