A legacy of conscience and community: the historic journey of Durban Indian Child Welfare Society

1927 to 1999

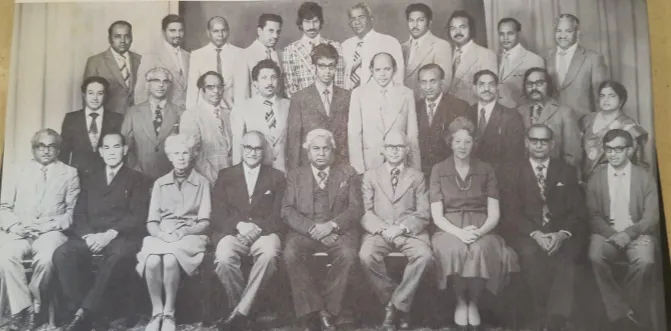

Members of the council of the Durban Indian Child Welfare Society, 1976 to 1977.

Image: Supplied

The Durban Indian Child and Family Welfare Society was a community-led initiative born out of adversity and reshaped child welfare in South Africa through resilience and innovation, writes Professor Dasarath Chetty in part one that reflects on the first 50 years of the society. He says at a time of increasing gender-based violence, child welfare societies assume increasing importance.

THERE can be no keener revelation of a society’s soul than the way in which it treats its children. This profound assertion by Nelson Mandela serves as the most fitting lens through which to view the 72-year history of the Durban Indian Child and Family Welfare Society (DICFWS).

From its inception in 1927 to its amalgamation with the formerly “white” child welfare society in 1999, the society was far more than a charitable organisation; it was the manifestation of a community’s soul, a direct and powerful response to a state that, by design, neglected and oppressed its children of colour.

Its story is a microcosm of the Indian community's broader struggle for dignity, rights, and survival in South Africa. The history of the DICFWS, which would later become the Child, Family and Community Care Centre of Durban (CFCCCD) in 1991, is one of relentless innovation born out of necessity. In a political and economic system that was exploitative and inhumane, the society understood that child welfare could not be addressed in a vacuum. It recognised that the need for support stemmed not from individual failings but from profound social deficits created by an oppressive state.

This holistic conception of welfare - the belief that a child's well-being is intimately interconnected with the health of their family, community, and political environment - was the philosophical foundation of the organisation. The very formation of the DICFWS was an act of political defiance. The colonial and later apartheid state offered only a "residual" approach to welfare for “non-whites”, a system that intervenes as a last resort and inherently blames the victim for their circumstances.

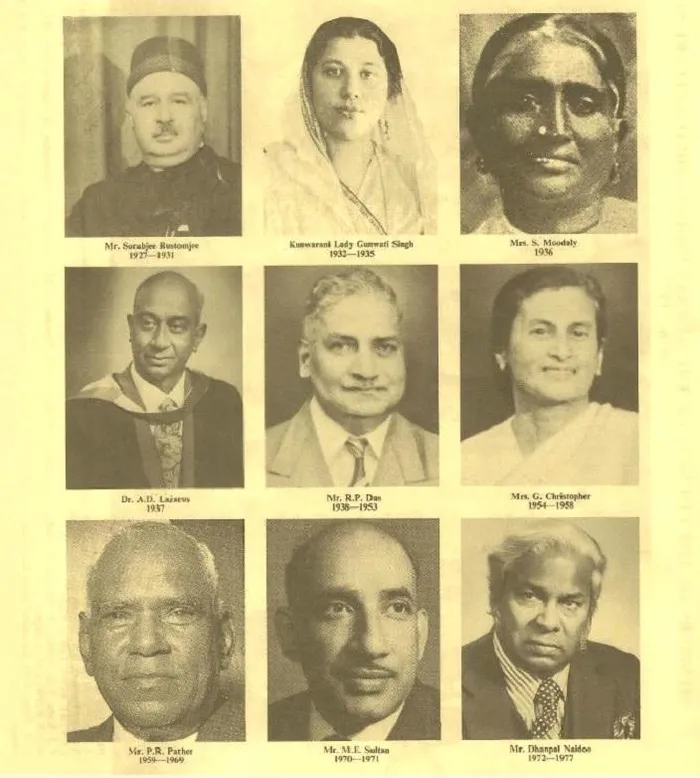

Presidents of the society (1927 to 1977).

Image: Supplied

In stark contrast, the state provided an "institutional" framework for its white citizens, viewing welfare as a necessary and ongoing function of a modern society. By creating a formal, structured, and proactive welfare society for itself, the Indian community was effectively building its own institutional system in defiance of its designated second-class status. It was a declaration of self-worth and communal responsibility, a profound political statement that they would care for their own when the state would not.

The Durban Indian Child Welfare Society (DICFWS) was born from the deplorable conditions forced upon the Indian community in the early 20th century. The legacy of indenture, which began in 1860, had left the majority of the community in abject poverty, living in unsanitary and overcrowded urban "barracks" or rural huts. High rates of infant mortality and illiteracy were rampant, locking generations into a cycle of deprivation.

This social crisis was not accidental but a direct result of a colonial economic strategy that prioritised profit over people. By importing mostly single male labourers, the British intentionally eroded the close-knit family structure dominant in India, leading to social isolation, violence, and tragically high suicide rates. As the community transitioned from indenture to other forms of labour, they were met not with support but with a rising tide of anti-Indian agitation and oppressive state legislation that restricted their rights to trade, own land, and move freely.

The society was formally established on July 23, 1927, at a meeting in the MK Gandhi Library, an initiative driven by the Indian Women’s Association. Under the patronage of Srinivasa Sastri, the first Agent General of India in South Africa, a committee was formed with Mrs S Moodaly as its first chairperson. By the mid-1980s, the organisation was the best known and most respected in the Indian community.

The honourable V Srinivasa Sastri with officials of the society (1927).

Image: Supplied

The organisation’s formative years were defined by the dedicated leadership of Gadija and advocate Albert Christopher, whose combined 30 years of service provided the vision and stability necessary for growth. The society’s political and social maturity was quickly reflected in its evolving constitution. An early amendment revealed a profound philosophical shift: from simply "promoting" welfare to actively working for the "removal of all conditions which are detrimental" to children's well-being.

In the context of a discriminatory state, this was a clear commitment to political change and a mandate for social action. This rights-based approach was embedded into the organisation's DNA. The society’s influence grew rapidly, particularly as it became a trusted intermediary for administering state maintenance grants, handling cases for over 1 000 families by 1947. Its success and model provided the impetus for the establishment of similar welfare organisations across Natal, making the DICFWS the kernel of an organised welfare movement.

As its responsibilities expanded, the society adopted an innovative and profoundly democratic model in 1948: the Local Committee system. Inspired by a similar structure used by the Friends of the Sick Association (Fosa), this system created a grassroots network of volunteers from specific neighbourhoods who investigated and supervised maintenance grant cases.

These committees, often led by respected community figures like teachers, became a parallel system of local governance in areas neglected by the state. The scale of their work was immense; by 1967, 46 committees were supervising over 4 000 families. The committees soon evolved beyond their administrative duties, becoming active cells in every functioning community. They organised sewing classes, established milk clubs, and became hubs of community development and empowerment.

The administration block of the Lakehaven Children's Home.

Image: Supplied

The system's genius lay in its democratic structure, where representatives from each local committee sat on the society’s highest decision-making body, ensuring that the leadership remained grounded in the community's lived realities.

The year 1959 marked a watershed moment with the opening of Lakehaven Children’s Home in Sea Cow Lake. This project was the culmination of years of community effort and represented a major strategic leap from non-residential support to full-time institutional care. Lakehaven became a powerful symbol of community self-help and a household name. The responsibility of running a 24-hour facility drove a process of professionalisation within the society.

To comply with the Children’s Act, the organisation formalised various standing committees to oversee its complex operations, with its structure evolving in direct response to the practical and ethical demands of its mission. Lakehaven also embodied a progressive philosophy of childcare. Rejecting the impersonal dormitory system of the era, the society pioneered a residential system approximating family life, creating a more nurturing, child-centric environment. It was designed to be a true haven where vulnerable children could find safety and stability.

Its creation solidified the DICFWS’s position as a leading welfare organisation, one that had forged a vital lifeline for its community in a heartless and neglectful state.

Three critical forms of intervention characterised the society’s early historical trajectory.

Firstly, it made a pioneering intervention, providing essential services that had never existed before for the community. Secondly, it made a service gap intervention, courageously filling the voids in care deliberately left by a neglectful state. Finally, and most significantly, it made social action interventions, aiming to initiate fundamental social change by tackling the root causes of social ills, including the role of the state itself.

This history is one of selfless service by unpaid volunteers, of participative democracy brought to life in the streets and neighbourhoods of Durban, and of a steadfast refusal to separate the welfare of a child from the fight for justice. It is the story of a community revealing its soul.

Professor Dasarath Chetty

Image: File

Professor Dasarath Chetty has been a volunteer and leader in the Child Welfare movement in South Africa, having served as President of Durban Indian Child Welfare Society (1994-1999), first president of the merged entity (now Child Welfare Durban and District), first black president of the SA National Council for Child and Family Welfare (2004 – 2008) and president of the transformed Child Welfare South Africa (2008- 2012).

* Today Child Welfare Durban and District (CWDD) will host its AGM. The president and board of governors of CWDD will be elected at the William Clarke Gardens Child and Youth Care Facility in Sherwood.

Related Topics: