From cane fields to courage: the legacy of South Africa’s Indian pioneers

'Their story is not just our history; it is our inheritance'

Consternation on the sea of faces ahead of their departure to an unknown land and the rigours of the servitude that awaited them. In fixing a gaze on this image, one is drawn into the desperate circumstances that forced Indians to bond themselves for periods of 5 to 10 years. There is no evidence of excitement or anticipation of what was to come.

Image: Stewart and Sara Fairbairn Collection

ON NOVEMBER 16, 1860, a British ship named the Truro sailed into Durban harbour, carrying 342 passengers from India, men, women, and children leaving behind hardship and hunger.

Ten days later, another vessel, the Belvedere, arrived with 351 more.

Together, these two ships brought not just people, but the seeds of a new community, one that would endure hardship, overcome injustice, and enrich the story of South Africa.

The India of the mid-1800s was a land of turmoil. Famines, taxes, and British colonial policies had pushed millions into desperation.

Recruiters called arkatis roamed the villages, promising good jobs and steady wages across the ocean.

For many, signing a contract they could not read seemed their only chance at survival. They were told they would work for five years and then return home.

Few ever did.

The Truro and Belvedere were not passenger ships but converted cargo vessels.

Below deck, hundreds were crammed together in stifling heat. Food was scarce, diseases spread quickly, and many perished before even reaching Natal.

Those who survived stepped ashore weak, frightened, and uncertain of their future.

They were sent straight to the sugar plantations, where the promise of opportunity turned to chains of exhaustion.

The days were long and hot, beginning before sunrise and ending after sunset.

Overseers ruled harshly, and wages were barely enough to live on.Between 1860 and 1911, more than 152,000 Indians came to Natal under the indenture system.

They built lives in barracks, sang bhajans in the cane fields, and prayed for strength under the African sky.

Out of the bitterness of bondage grew resilience and faith.Some could not bear the suffering. Colonial archives tell haunting stories, fathers and sons who ended their lives on railway tracks, and young girls who took their own lives in despair.

Historians have found that the suicide rate among indentured Indians was once the highest in the world.

Yet, even through tragedy, the spirit of survival endured.When the indenture system ended in 1911, India had said “enough” to the exploitation of its people.

By then, however, the descendants of those early pioneers had already begun to make Natal their home.

They built temples and mosques, started schools, and created a community bound by shared struggle and hope.

They tilled the soil not just for sugarcane but for the growth of a new identity South African Indian. From those roots came generations who rose to greatness: teachers, traders, professionals, activists, and leaders who helped shape modern South Africa.

The story of the Truro and Belvedere is not only about hardship. It is also about courage, the courage to adapt, to rebuild, and to rise. From bondage came freedom; from struggle came strength.

The men and women who once cut cane in the blazing sun laid the foundation for a thriving community that now contributes to every aspect of national life.

Their legacy lives on in every act of compassion, every family tradition, and every achievement of their descendants.

It is a story of ordinary people who became extraordinary through endurance and faith.This year, as we mark 165 years since that first landing, we remember not only the pain but the perseverance.

The arrival of the Truro was not the end of hope, it was the beginning of a new chapter.

The indentured labourers came with little but left us much: a legacy of discipline, humility, and the belief that dignity can survive even the harshest trials.

They turned hardship into heritage and adversity into achievement.As their descendants, we honour them best not through sorrow but through celebration by standing tall, united, and proud of who we are.

Their story is not just our history; it is our inheritance.

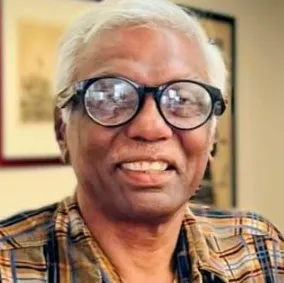

Jerald Vedan

Image: Supplied

Vedan is an attorney, civic leader, and writer on South African Indian history. He served as a councillor for Shallcross and continues to promote cultural heritage and social cohesion.