TO QUEUE OR NOT TO QUEUE

DURBAN INDIAN

The author has fond memories of his mother's shopping at NU Shop and catching the local buses.

Image: SUPPLIED

MY MOTHER just could not queue. I remember sometime in the 1970s when the buffet station came into fashion.

You could take your plate and pick whatever you wanted from a whole spread of dishes.

Not my mother. She would politely find a seat and keep an eye out for someone who looked like the manager.

After a quiet word, her plate would be brought to her table with a simple selection of the morsels she wanted to eat.

When I tried to explain to her the delights on the display her retort was usually, "I am very sorry. I won't queue for food."

She did not stop me though.

Her advice was simply: "When you dishing int he buffet, always think of the person behind you."

She would not queue at the door for the annual NU Shop sales either.

Once the crowds that had been in the line since 5am crashed through the door pulling, pushing, cursing and even biting, she haughtily ambled in.

If there was not anything to her liking on the racks or in the sale bins, she would turn to one of the shop assistants with a smiling hand signal.

"Darling, is there anymore more of the 99c pyjamas you advertised in the paper? Maybe in the storeroom? Two mediums in green checks if you can find them."

Lo and behold, the sale pyjamas in the exact colours and size appeared. In no time at all, more goods that she was keen on also made an appearance from the back.

My mother figured that the shopkeepers had a method of putting out the "hook" items in dribs and drabs.

They understood the shopper's mentality that if you found a bargain, you might as well buy the higher priced item too while you were in the store.

I always have a little chuckle about those supermarkets which advertise dhania for 50c a bunch. That price is usually well below what they pay the farmers but it is the hook to reel punters into the shop.

Everybody who goes for two bunches dhania comes out with five litres of cooking oil or four tin fish at the regular or inflated price.

When we went vegetable shopping at the Early Morning Market on Warwick Avenue, my mother had this system of walking all the stalls greeting people.

It was also her method of comparing the price and quality of what she needed.

How often has it happened at Bangladesh or Verulam markets that we see something cheaper moments after we have already paid for them?

If she came across something that was popular with shoppers, she just stood at the back and gave a hand signal, very much in the same code that one stops a minibus taxi these days.

Her items were in her hands quick as a flash. The horrifying part for me was when we got to the Victoria Street bus rank. There would be a queue. Not for my mother though.

As she approached with bags and baskets in tow, the conductor would dash to her grabbing the shopping and ushering her straight to a seat behind the driver.

I remember those bullnose buses that had an engine cover. My mother's shopping would be knotted and propped there so that she did not have the discomfort of bags on her lap or by her feet.

If my mother were alive today, her double might be the Taxi Queen who always gets the best seat next to the driver even if it means throwing outa passenger.

She always paid the fare though. "One full and one half."

In those days children could travel at half price.When I arrived in England as a young student, I admired the silent, straight linesBritish people made at the bus stop.

As an act of rebellion against my mother, I never cut the queue. At the Indian Affairs office, I recall my mother trotting into the austere doorway in leather courts and a knotted silk scarf long before Lady Diana made that ensemble famous.

As she entered the sweaty hall with rows upon rows ofwooden benches of the huddled faithful as if they were in a Catholic cathedral, an official in lamb chop sideburns, Rajnikant moustache, Jan Van Riebeeck hairstyle, a checked short-sleeved shirt, garish broad gaberdine tie, bell-bottoms and Jordan peacemakers would stride forward: "Good morning, Mrs Naidoo, and what brings you here today?"

One of those heavy government chairs with government armrests would be pulled up for her. Government forms notarised with government rubber stamps and government black ink were folded into a brown government envelope by government officials.

We were out of the government offices in a jiffy.The one place I recall that my mother had no choice but to take her place in the queue until she was called was the mother's clinic in Unit Two in Chatsworth. The nurses there managed the place like generals in the Indian army barking names and instructions.

There was one exception though. A gentle, greying woman of slight build called Mrs Murugan who spoke softly and calmly, often in Tamil or Telegu.

"You must give this child Pronutro, ma. He is very thin for his milestones."

The breakfast cereal came in a plain plastic bag for 10c. I wish Mrs Murugan could see me now shopping in the XL aisle and following every fad diet on Facebook.I did not mind the queue in the clinic.

I found the stern nurses in starched uniforms, pips on their shoulders and laddered stockings frightfully attractive.

Much better if they were well built with plump ankles and swaying bottoms.

Right from childhood, I could easily have been a consultant for Fifty Shades. I dared not broach the subjectof cutting queues with my mother for fear that she might stop taking me to the clinic.

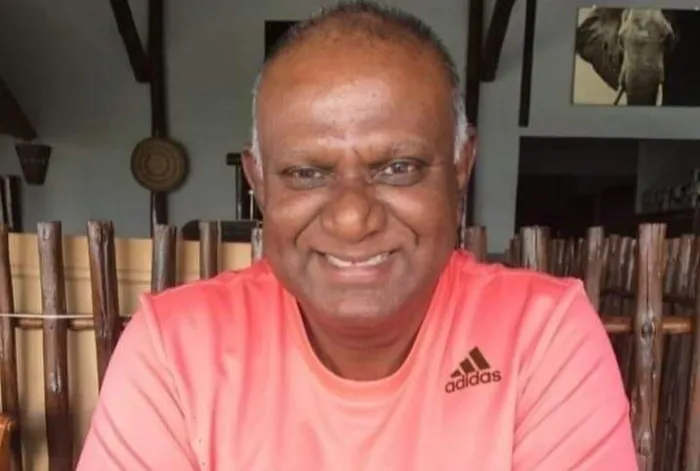

Kiru Naidoo

Image: File

Make a diary date to catch Kiru Naidoo at the Books and Chai Festival at the Umhlanga Apart-Hotel Hotel on Meridian Drive all day on 30 November.

He may be reached on 0829408163.