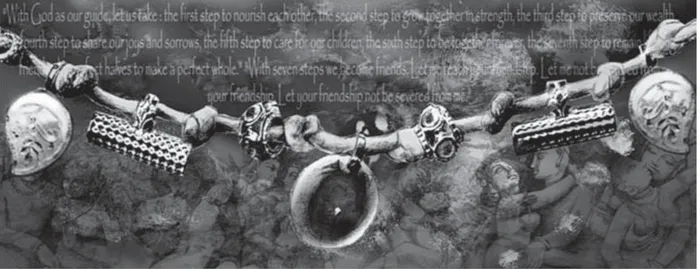

Thali, 2009, digital screen print with oil paint on canvas

Image: Selvan Naidoo

IDENTITY always comes into question when in crisis, and no community is more often in crisis than the Indian South African, particularly as they have had to navigate various iterations of themselves over the past 165 years.

Crisis is a strange entity to observe with the naked eye, as it operates in the subliminal spaces of culture and society, in the hidden agendas of public platforms, and in the political frameworks of the country. One space, though, where crisis is clearly visible is in the arts of a community.

From their arrival in 1860 under indenture, Indian migrants brought with them all forms of art practices such as devotional music, folk dances, ritual performance, and crafts. These cultural practices served both as comfort in reminding them of their homeland and resistance in preservation amidst a shifting new place called home. These creative practices preserved memories of India, religion, and community when colonial and plantation systems sought to reduce lives to labour and discipline.

Over decades in South Africa, Indian religious institutions were cultivated in temples, mosques, and churches and became spaces not only of worship but of cultural education with songs, dance, and visual culture shaping early forms of collective Indian identity.

Of course, colonialism and apartheid cast a long and dark shadow over the creative canvas of Indians in South Africa. Yet, as is the nature of creativity, it persisted and flourished even in a country burdened by pariah status. In many households, dance was sustained by imitation of routines seen in Indian films screened at Durban cinemas such as the Shah Jehan, the Odeon, and the Raj.

These cinemas offered a fleeting glimpse into the song and dance traditions of India, and young dancers painstakingly reproduced them as a way of preserving a cultural art form from which they had been severed. Journeys to India were prohibitively expensive and undertaken only by a few, who returned with training in classical forms such as Bharata Natyam and Kathak at their own personal cost.

Their dedication became a lifeline for South African Indian cultural memory. These pioneers introduced not only Bharata Natyam but also folk traditions such as gommie and kolattum, teaching them to younger generations and promoting them through platforms like the Natal Tamil Vedic Society’s Eisteddfods. In those early years, dance was practised and performed in its purest form, an act of cultural preservation against the threat of erasure. Over time, however, dancers came to recognise that their South African location called for adaptations, creating performances that honoured tradition while speaking to their lived reality in a new land. Surialanga’s offerings are a case in point.

In addition to the dancers, visual artists were also at work, often in the silent corners of the country. Among them were street or pavement photographers who, by capturing everyday street scenes, inadvertently preserved fragments of Indian South African life, freezing moments of culture through their lens.

More established figures such as Ranjith Kally, Omar Badsha, and Jeeva Rajgopal emerged as icons of South African photography. Their compelling images ensured that the Indian voice was not silenced or erased amidst the pressures of assimilation into broader South African society. Through their work, community life, with all its struggles, protests, moments of joy, and celebration, was carefully documented. In doing so, these photographers played a pivotal role in preserving the historical narratives of a community that often found itself negotiating crises of identity and belonging.

When it came to visual art, few Indian artists gained recognition prior to the establishment of the University College for Indians, later known as the University of Durban-Westville (UDW), which, from the 1960s onwards, opened a crucial avenue for fine arts production. Between 1962 and 1999, the university produced a generation of fine artists of Indian ancestry whose work, though often created within a student context, revealed layered negotiations of politics, race, and identity. Yet much of this artistic output was poorly documented in national art histories and consequently excluded from the broader South African art narrative.

Interestingly, the trajectory of their work illustrates a gradual shift: from the austere to the secular and religious, and later to explorations of identity in a newly democratic South Africa. Artists such as Ashley Munsamy produced artworks reflecting the life of the community, while Vedant Nanackchand and Clive Pillay turned to overtly socio-political themes.

Today, Indian South African artists continue this legacy by addressing a wide spectrum of contemporary concerns, from human trafficking in the work of Vas Putter, to explorations of mother worship in Kaylin Moonsamy’s and Reshma Chhiba’s practice, to the re-examination of indenture in Selvan Naidoo’s projects, thereby collectively extending and diversifying the visual vocabulary of the Indian diaspora.

Additionally, exceptional sculptors such as John Pillay have contributed to the creation of temple murthis, a sacred art form that is increasingly at risk of disappearing in South Africa.

As we mark 165 years of Indian presence in South Africa, it is remarkable to reflect on the shifts that have taken place in the arts, particularly in dance. Bharata Natyam, once practised with rigorous discipline and fidelity to form, is now evolving in ways that have raised questions about authenticity.

Increasingly, dancers are less familiar with foundational techniques such as aramandhi (the basic half-sitting posture), facial expressions are often absent, and the arangetram, once a public demonstration of a dancer’s skill and a teacher’s rigor, has become an exclusive and private event. In the 1970s, '80s, and '90s, arangetrams were community occasions where both dancer and teacher had to prove the calibre of their work before a discerning audience. The shift towards private ceremonies risks diluting standards and raises questions about the future of this art form in the coming decades.

While there is certainly space for diverse expressions, from Bollywood to fusion, every form must uphold quality if it is to command respect and endure. Yet as 4th, 5th and 6th generation Indians in South Africa, it is inevitable that art forms will transform, and this may be part of the natural trajectory of diasporic culture. What remains vital though, is the role of keystone teachers such as Manormani Govender, Kantharuby Munsamy, Vasugi Deva Singh, Yogambal Singaram and Smeetha Singh, whose dedication over many decades has safeguarded the integrity of Indian classical dance in the diaspora.

For these traditions to survive, however, the community must provide both patronage and platforms. The creative economy requires investment, and sustainability will only be achieved through collective support. Established festivals such as the Durban Diwali Festival are crucial in sustaining and celebrating visual and performing cultural practices.

At the same time, new initiatives such as the Red Mango Arts Festival, launched in Durban to coincide with the 165-year commemoration, signal fresh directions. By curating works that highlight intergenerational voices, personal histories, and neglected stories, such festivals demonstrate how the arts can serve as instruments of visibility, education, and cultural connection. They remind us that, despite challenges, creativity continues to be the lifeblood of a community that has survived, adapted, and flourished for over a century and a half in a country that was often hostile to their presence.

The Indian South African diaspora’s artistic production over the past 165 years is not merely an episodic footnote in South African history. Its visual and performing arts are archives of lived experience, of migration, labour, cultural borrowing, resistance, and coherence. Art is how a community tells its story when formal records silence them.

As we mark this anniversary, the question is: will the wider country recognise these artistic legacies as part of our shared heritage? Will galleries, theatres, schools preserve, teach, exhibit, and invest in them? Because through colours, rhythms, voices, sculpted forms, the Indian South African arts do more than speak, they demand that identity, history, crisis, and hope, be seen.

Professor Nalini Moodley

Image: File

Professor Nalini Moodley is the Executive Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Design at the Tshwane University of Technology. A leading scholar, cultural practitioner, and academic administrator, she holds a PhD in visual art, an MA in the history of art, and an MBA in education management.

Related Topics: