Exploring the true origins of the bunny chow

Culinary history

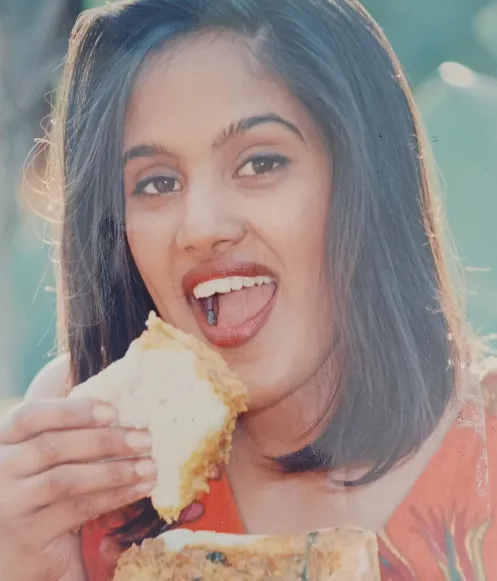

Actress Leeanda Reddy tucks into a Durban bunny chow back in the day when like cookbook author, Madhur Jaffrey, she was a young actress.

Image: Shelley Kjonstad / Independent Media Archives

IN THE food mythology of South Africa, there is a neat mantra in every storyteller, paragraph in every glossy magazine spread or lyrical blog that the bunny chow, that divine, gravy-soaked quarter-loaf of fluffy white bread hollowed out and filled with curry, was born in the 1940s among the Gujarati Hindu merchant community of Durban's Grey Street.

The dish is fabled as a quick lunch for caddies barred from the club houses of the Europeans-only golf courses or perhaps workers who needed something cheap and nourishing that could travel without packaging. The story is repeated with such confidence that to question it feels almost like the blasphemy of asking a holy book whether it has remembered itself correctly. And yet. What if the true origin of the bunny chow is not nearly so convenient? What if the dish first appeared, unheralded and unnoticed, in a kitchen somewhere across the ocean, the off-hand creation of a child keener on hopscotch than golf or was simply trying, on a hungry after-school afternoon to mop up curry gravy from the lunch leftovers?

One must hesitate to upset the faithful by tickling holy cows. Durban has after all embraced the bunny chow with an unquestioning pride that borders on the bravado of a well-suited evangelist. History, like bread, is often hollowed out to make room for what we prefer to swallow. But late at night, when the archives and raconteurs have fallen silent along with the rest of the household, a book stealthily picked off the shelf in the hope that it might serve as a sleeping pill ends up having an arousing effect.

Acclaimed British-Indian food writer, Madhur Jaffrey, penned a delectable compendium titled: "A Taste of India - the definitive guide to regional cooking". It is hardly the book one should take to bed but she turned out to be a most satisfying companion. Googly-eyed, I was taken on a mouthwatering tour.

Kiru Naidoo

Image: File

Jaffrey recounted: "In Tamil Nadu, for example, I have been served food preceded by remarks such as 'this is a typical Iyer Brahmin dish' or 'only we Chettiyars make this'. The Muslim Moplas of Kerala serve stunning rice pilafs as most Muslims do throughout India. Pilafs, after all, came to us from the Middle East ..."

There is the ready acknowledgement of foreign influences in Indian cooking which were without ceremony transformed with a distinct Indian touch. When she got to the breads, I peaked up a bit more. The salacious descriptions of rotis, parathas, chapatis, naans and shirmals left me salivating.

"Those with natural yeast managed to rise ..."

And then as the excitement was building, she dropped me by introducing those lack lustre northern marauders who colonised the globe ostensibly in search of spices but ended up with the floppiest dishes on the planet. Can one image anything more tasteless than thickly battered fish and chips or mushy peas? Jaffrey concedes though: "The Europeans ... outdid the Muslims coming in with fat, yeasty loaves. The first Indian to set eyes on them must have been left quite stunned. The Indians called this new bread dubbel roti or 'the double bread' and happily used it to mop up the good juices of many spicy stews."

She had me going again. There was something oddly familiar about mopping up gravy with this British bread. She went on to tell the story of one of her favourite treats as a child in Delhi in the 1930s of kicking off her restrictive socks and shoes after school and heading to the pantry where an "obliging oven" kept warm leftovers from their parents' lunch. Jaffrey and I once talked animatedly about her childhood, stealing a few moments as she finished her book signing session at the Jaipur Literature Festival and before the organisers dragged her before the paparazzi.

She told me that she was born in Lucknow and that her childhood and teenage years were in Delhi, living in a large joint-family home in the Civil Lines enclave. She went to school there. Queen Mary’s, I think, and later Delhi University where she studied English and performed in amateur theatre. Her conversation was calm and attentive unlike Shashi Tharoor or Manisha Koirala who were harried by the Invisible Man tugging at their sleeves to talk to the next punter. Back to the bread in the book.

Jaffrey recalled: "... we would slice off about two inches (5cm) from the end of a crusty dubbel roti. The softy, fluffy part of the slice would be dug out ... The hollow that resulted was filled with meat korma or whatever dish happened to be in the oven."

That sultry evening as the strawberry moon peered inquisitively from outside my bedroom window, I was gobsmacked! Is this not the Holy Grail of the bunny chow? Was she not talking about precisely the iconic dish that the Kapitans and Patels have been jousting on the length of Grey Street for almost a century? Jaffrey is probably the most highly regarded food writer of the subcontinent.

One would be hard pressed to doubt her authority more especially when she brings her mother into the story. "Of course, when my mother yelled out, wanting to know who had cut off both ends, of both loaves of bread, we just giggled hysterically ..."

Does that settle the matter of the inventor of Durban's bunny chow? It's food for thought at the very least.

Kiru Naidoo fancies himself as a local historian and writer. His latest book, Durban Indians, is available from www.madeindurban.co.za. He may be reached on 082 9408 163.