When the security police came knocking: memories of press persecution under apartheid

Book extract

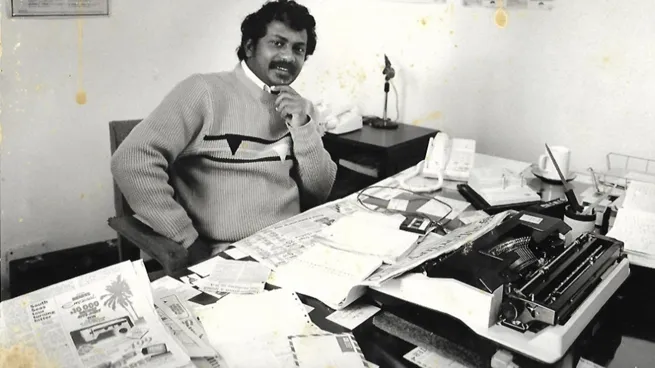

Subry Govender when heading the Pres Trust News Agency in the mid-1980s.

Image: Supplied

"HEY look at what this c***ie journalist has been scribbling on the wall! You are wasting your time. We are not going to let that terrorist out of prison. He will rot in jail."

It was around 3am in the morning on a weekday in the fourth week of May 1980. I heard frantic knocks on our door. It was my mother. Speaking in our Tamil mother tongue. She said: "Sadha, rende vela karagango inga irakarango. Una pakanoma."

(Translated: “Sadha (that's my cultural name) two white men are here. They say they want to see you.")

My wife, Thyna, and our son, Kennedy Pregarsen, and daughter, Seshini, and I, used to occupy at that time the outbuilding at number 30 Mimosa Road, Lotusville, Verulam - just north of Durban.

My mother, Salatchie, my father, Subramoney Munien, and my brothers - Dhavanathan (Nanda), Gonaseelan (Sydney), and Gangadharan (Nelson) and sisters - Kistamma (Violet) and Natchathramah (Childie) - used to occupy the main building.

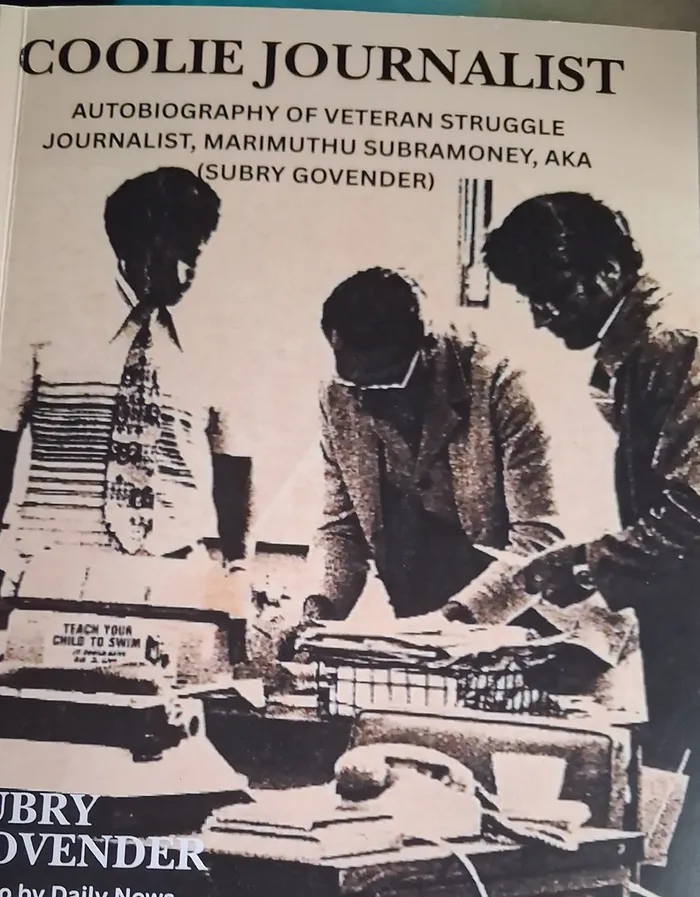

Subry Govender launched his autobiography on Sunday.

Image: Supplied

My eldest sister, Mariamah (Ambie), was married at this time and she was staying in the area of Phoenix - about 15km south of where we were residing.

Clearly in a sleepy mood, I opened the door to find two white security policemen with awkward smiles on their faces. I recognised one of them as Sergeant De Beer. He was one of the security policemen who questioned my position when I worked at the Daily News from the early 1970s to late 1980.

I saw him questioning one of my Daily News colleagues outside the Daily News building at the former Field Street in the city of Durban. My colleague informed me later that De Beer had questioned him about my work at the Daily News.

On this occasion at my home in Lotusville, Verulam, he looked at me and with a quirky smile and said: "Mr Subramoney, we have come to search your house and for you to accompany us back to the office."

At the same time, members of the security police were conducting similar raids at the homes of my colleagues and officials of the Media Workers Association of South Africa (MWASA) in the cities and towns of Johannesburg, Pretoria, Cape Town, Port Elizabeth, East London, Bloemfontein and other parts of the country.

In addition to us as journalists, the security police also raided the homes of political activists, such as Vijay Ramluckan, who became one of Nelson Mandela’s doctors after his release in 1990, and Yunus Shaik, brother of Moe Shaik who became an ambassador in the new South Africa.

I informed De Beer that my family members were asleep and their visit was inappropriate. Their unannounced visit at such an unearthly early hour was an intrusion and would be disturbing my family. De Beer did not seem to care and he and his colleague just pushed their way in.

"Where are all the communist books you keep?" De Beer and his colleague asked in gruff voices.

"I don't know about communist books but here are all my files and literature," I responded.

I did have some communist literature but this was stored away in the ceiling of the house. I used to receive material from the banned Communist Party of South Africa despite me not being a member. I used to read the booklets and then store them in the ceiling.

"We want you around when we search your files and books," they said.

So, I watched them go through my files with a “fine tooth comb" and read each-and-every letter in one of the files.

Suddenly they burst out laughing and one of them said: "Here's an interesting letter."

It was a letter I had written sometime in the late 1960s to the then Prime Minister of India, Mrs Indira Gandhi. I was still a "greenhorn" at that time. I was just learning about the political situation, the world and the land of my ancestors - India. I did not know what went through my head that one fine day I sat at my typewriter and penned a letter to Mrs Gandhi. I told her about the oppression of the people of colour in South Africa and asked her whether India was doing anything about it. Mrs Gandhi knew something about South Africa.

As a teenager she stayed a few days in Durban while enroute from London to India. She was the guest of members and officials of the progressive and influential Natal Indian Congress, a powerful ally of the African National Congress (ANC) during the dark days of the struggle against white minority rule and domination in the 1940s, 1950s, 1960s, 1970s, 1980s and early 1990s.

I was informed that two of the people she had met were struggle stalwarts, Mr Ismail Meer, who was a member and official of the Natal Indian Congress, and his wife, Professor Fatima Meer, who was a sociologist, author and social activist at that time.

The letter to Mrs Gandhi read: "Dear Mrs Gandhi. I am a South African whose forefathers and mothers had come down from India to the country since the 1860s to work as indentured labourers on the sugar cane plantations of the former Natal Colony. Our people have made great strides despite decades of slavery, colonial rule and apartheid oppression.

"Leaders of our community such as Dr Yusuf Dadoo, Dr Monty Naicker, Dr Kesaval Goonum, George Singh, JN Singh, Ismail Meer, Fatima Meer, Billy Nair, Mac Maharaj, Sonny Singh and thousands of others have made enormous contributions and sacrifices in the struggles against White minority rule and oppression. The situation is now deteriorating and I would like to know whether the Government of India will be doing anything to promote our liberation."

I did not post that letter. But I did not tell the security policemen that. I wanted them to believe that I had really sent that letter to Mrs Gandhi.

After about an hour of searching through my files, the two security policemen put everything they wanted together in a pile and then told my wife: "You are not going to see your husband for some time. He would need some clothes."

Subry Govender is a veteran Durban based struggle journalist

This is an extract from his autobiography, Coolie Journalist, which was launched last Sunday. Email him at [email protected] or call 082 376 9053.

Related Topics: