A lifelong journey in science and service: The remarkable story of Professor Quarraisha Abdool Karim

INDELIBLE CONTRIBUTIONS

Professor Quarraisha Abdool Karima, a world-renowned infectious disease epidemiologist and the associate scientific director of the Centre for the Aids Programme of Research South Africa (CAPRISA).

Image: Nadia Khan

FOR the past three decades, Professor Quarraisha Abdool Karim, a world-renowned infectious disease epidemiologist and the associate scientific director of the Centre for the Aids Programme of Research South Africa (Caprisa), has made an indelible contribution globally through her research on HIV and Aids.

In addition to her numerous local and international recognitions for her contributions to science, the 65-year-old of Musgrave was recently elected as a fellow of the Royal Society, the world’s oldest and prestigious scientific academy.

Childhood

For Abdool Karim, who is the third born of nine children, her journey stemmed from humble beginnings growing up in Tongaat.

Her maternal great-grandfather came to South Africa in 1860, and served as a mediator between the indentured labourers and the British.

“He had a farm in Emona which my grandmother, Narainamma Saibe, took care of. I remember her quite well. She must have been in her sixties when I was born. She lost her mother at a young age and had to take care of her siblings and the farm. She later married their family’s accountant, Mohamed Saibe.

"He came from a well-known and influential family in Tongaat. My grandfather’s family were involved in community service. In those days malaria was very common and he was in charge of a committee to help people. I never had a chance to meet him, but I would have loved to have asked him about his involvement in public health.

“Later on, when my mother, Zanib, married my father, Ahmed Abdullla Khan, they moved to my childhood home in Plein Street. My grandmother lived with us and played an important role in my childhood. She was hardworking and highly respected in the community. There was always a constant stream of people coming in and out of the house seeking her wise counsel.

“My grandmother was also entrepreneurial. She would make and sell samoosas. I would help her by separating the pur. I must have been about six or seven years old at the time. She woke up at about 5am to fry the samoosas and I would walk to this bakery run by two Greek sisters on the main road to drop-it off. When I returned from school, I would go to the shop and butchery to buy the ingredients for the next batch and help her again.

“She also used to ask me to massage her legs, which I did on condition that she tell me stories of her life while growing up such as living through two world wars and the locust plague. I loved those moments with her,” she said.

Abdool Karim, left, with her siblings.

Image: Supplied

Abdool Karim also recalled helping her parents in their vegetable garden which was used to sustain their home after their shop burnt down.

“My parents had a clothing and material shop, however, just before it could be sold it had caught on fire. We lived a comfortable life but everything changed overnight. However, my parents were resilient and acted immediately by starting to plant vegetables that didn't require a lot of time to grow. My siblings and I would help them plant, water and harvest the vegetables. They had buyers from the morning market and on weekends, my sister and I would go sell whatever was leftover at the market.

“I had a beautiful childhood. I was never lonely as I had my siblings and the children from the community who we played with. We had a big front yard and a long driveway where we would all gather and play games such as three-tins, statue and hopscotch. We would also celebrate all the different festivals together such as Diwali, Christmas and Eid,” she said.

Education

From the age of three, Abdool Karim attended the Vishwaroop State-Aided Indian School.

“I was a curious child and always asked questions. My parents, even though they never went to university, taught us a lot about critical thinking and ‘not to follow the sheep’. They also did not tell us to be quiet when we asked questions. At the time, my uncle was the school principal and he agreed to let me attend. I was put into class one. I remember I had a lovely teacher who always encouraged me to do my best.”

After completing her Standard five (Grade 7), Abdool Karim said she attended Victoria High School for a year, before matriculating at Tongaat High School in 1976.

She said it was during this time that she realised that she wanted to be a scientist.

“I loved all of my subjects, but accounting and science were my favourite. However, I was more drawn to science as it allowed for forward-thinking and as someone who was always asking questions, I found it to be more suited to my future career decision. I remember when I told my father I wanted to be a scientist he asked if I would earn enough, but I told him I am not worried about that, I want to do something that I would enjoy. It was one of the best decisions I could have made,” she said.

Abdool Karim graduated with her Bachelor of Science (BSc) degree at the University of Durban-Westville in 1982.

Image: Supplied

University

Abdool Karim pursued a Bachelor of Social Science (BSc) degree at the University of Durban-Westville in 1977.

“However, the following year I took a gap as my mother had health issues and I had a younger brother. So I stayed at home to care for them. I returned to university a year later. I also took a few extra classes in chemistry 2 and maths as I wanted to major in biochemistry. I completed my studies in 1981 and graduated in 1982 with my BSc degree with majors in microbiology and biochemistry.”

Abdool Karim said she was also actively involved in the student protests.

“When I was not in class or studying, I joined fellow students who were protesting against inequalities. I remember how the police used teargas and batons to disperse the large crowds of students."

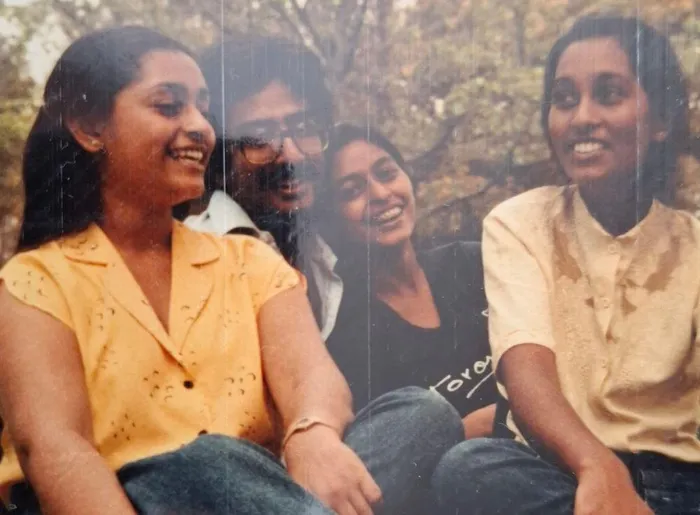

Abdool Karim(left), with her two sisters and brother- in-law.

Image: Supplied

Career

Abdool Karim said during her studies she developed an interest in immunology.

“It was part of teachings during biology and I was intrigued by how the body defended itself. However, at the time there were only two or three people in the country who specialised in immunology. One of which was a professor in Pretoria. I decided I must meet him.

“At the time my sister was studying dentistry at a university in Johannesburg. I took a taxi from Durban to Johannesburg, then a train to Pretoria in January 1982. When I arrived there, I was told I was not allowed to take the bus. I remained undeterred and took a taxi to the Wits Medical School. However, I soon learnt that you had to make an appointment. But I could not wait days to meet him, so I sat outside his office everyday. Until one day, he finally met me. I told him I want to learn about immunology. He told me he didn’t have a job for me, but I said I just want to learn.

“He then introduced me to Professor Ruben Sher, who also looked after the laboratory of the South African Institute for Medical Research (SAIMR). At the time he was doing work on leprosy. While I was with him working as a medical technologist, I learnt all I needed to know about immunology. It was also during this time that the first cases of AIDS were reported. At that stage we don't even know what caused this new disease which was affecting gay men. He had opened up his offices to people affected and was running every possible assay trying to understand what was going on.

“However, I remember a student from the university’s medical biochemistry department had come in with specimens from people with autoimmune diseases. I was curious and started talking to him about it. I decided after a year at SAIMR that I am going to return to my studies and do my honours degree in medical biochemistry,” she said.

Abdool Karim said after graduating with her honours, she was recruited to work as a medical technologist in the Iron and Red Blood Cell Metabolism Unit - Thomas Bortwell's Laboratory at Wits University in 1984. She remained there until 1986.

During this time she also completed a two-year higher education diploma at Unisa.

“I woke up one morning thinking why aren’t there more ‘people of colour’ studying science. I saw while studying over the years. I thought maybe I could do something to encourage young people to study science and pursue a career in the field.”

Abdool Karim said in 1986 she returned to KwaZulu-Natal and taught maths and physical science at a high school in Verulam.

“However, that was only for a few months and I thereafter started working in the chemistry laboratory at the University of Durban-Westville. While there I saw a junior researcher position in the Department of Hematology at the then-Natal University. I thought this is what I wanted to do as it was a job which would get me back into medical research. While there I did studies on Beta thalassemia. This is a blood disorder which was found to be quite common in people of Indian origin ancestry.”

Abdool Karim, with her husband Professor Salim Abdool Karim, and their children, Wasim (seated), Aisha (Standing, left) and Safura.

Image: Supplied

She said during this time she met her Professor Salim Abdool Karim, a world- renowned epidemiologist and virologist, whom she married in 1988.

“He was working in the Department of Virology. However, he was leaving to do his Master's degree in public health at Columbia University in August that year. I thought I would not see him again. But in December that year, he proposed to me over the phone. We were married the following year in January, and I left South Africa to do my Master's degree in parasitology also at Columbia University. I thereafter worked in one of the laboratories as a graduate research assistant.”

The couple have three children, Safura, 33, a human rights lawyer; Aisha, 30, a journalist and masters degree in public health student at Columbia University ; and Wasim, 26, a software developer.

Abdool Karim said while in New York, it was discovered that HIV was the cause of Aids.

“I was interacting with people from Africa who were giving lectures. My husband and I started asking questions about what do we know about HIV. In 1989, when we I returned to South Africa, I was recruited as a scientist by the South African Medical Research Council

“At the time, there were just a handful of studies on HIV being in South Africa. As an epidemiologist, who is someone that studies diseases in the population, I needed to know what was the problem and how big it was. This led me to doing my first population based study on HIV. The study showed that young women bore the brunt of the HIV burden. Women under the age of 25 were getting infected by men over 25. The women were also getting infected 7 or 8 years before we could see HIV in men. When you get data like that you have to do other studies to figure out why and how. So that is how my research started.

“I hosted meetings once a month that were open to the public and to other clinicians and scientists in the province to share what we were learning about HIV, because it was increasing and spreading so fast. While it was impacting the African community more so than other race groups, the speed of it was starting to be ascribed as a generalised epidemic,” she said.

Abdool Karim said in 1992, she did the first study to try and find technology that women can use to protect themselves.

“I said I am going to find something. We were doing a whole range of things to try and understand the unfolding epidemic. It took 18 years and with many failures along the way, but we demonstrated for the first time in the world the first proof of concept that antiretrovirals (ARVs) could be used by uninfected individuals to prevent HIV acquisition.”

Over the years, Abdool Karim was instrumental in various programmes including setting up the National Aids Programme post democracy in 1995.

“At the time I was seven months pregnant with my second child. It was challenging creating a balance between being a parent and doing research as well as setting up and implementing programmes, and delivering services. In parallel to the research we also trained over 600 South Africans who worked in laboratories and universities in the US.”

Caprisa

Abdool Karrim said she together with her husband had applied for an international grant to open up Caprisa.

“We were now post-1994 and did not have all the sanctions that were in place under the apartheid government. However, the type of research we needed to do, such as developing drugs, diagnostics and therapeutics required a lot of money. While the Department of Science, Technology and Innovation does put in some money, it is not enough. So most people doing high level and impactful research apply for grants.

“We applied to the US National Institutes for Health (NIH), the biggest funders of biomedical research. Doctor Anthony Fouche, the head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases at the NIH who had seen what is going on in South Africa said the priorities in different parts of the world are very different from the US, so he did what is called a request for applications. We decided to apply for a grant and said we would go in with two big questions - how to prevent infection in young women and how to prevent people from dying from HIV and TB infection.

“The grant not only enabled us to set up the centre but also gave us enough funds to set up infrastructure such as clinics to do the research as well as to have staff such as statisticians and pharmacists. We could also train people and create opportunities for masters, doctoral, post-doctoral and medical students. The centre was set up in 2002.

“Over the years we have continued with research and have several trials underway. We have also made major breakthroughs and are showing the world that Africa can produce high quality and impactful science that benefits all of humanity. It has been a long and challenging journey, and there are many failures that come with research but with that you learn more and keep asking questions,” she said.

In addition, Abdool Karim is a professor in clinical epidemiology at Columbia University and does lectureships at universities across South Africa and internationally.

She is also the president of The World Academy of Sciences, a member of the US National Academy of Medicine and American Academy of Arts and Sciences, as well as a fellow of the International Science Council, African Academy of Sciences and the Royal Society of South Africa.

Abdool Karim(fourth from left), was named in Forbes Africa list of 50 women over 50 leading throughout Africa.

Image: Supplied

Accolades

Over the years, Abdool Karim has received numerous prestigious local and international awards, including the John Dirks Canada Gairdner Award for Global Health, the Christophe Mérieux Prize from the French Academies of Sciences and the 500 years of the Straits of Magellan Award from the Chilean government.

She was also the recipient of the John F.W. Herschel Medal from the Royal Society of South Africa, the TWAS-Lenovo Prize from The World Academy of Sciences, the Academy of Science of South Africa Science-for-Society Gold Medal and the South African Medical Research Council Gold Medal.

She, together with Professor Salim Abdool Karim were co-awarded the 2024 Lasker-Bloomberg Public Service Award, for their work on HIV prevention, treatment, and advocacy.

She also won the 2024 Forbes Woman Africa Academic Award.

Abdool Karim had also received honorary doctorates from the University of Johannesburg Stellenbosch University and Rhodes university, as well as from the KL University in India, Rockefeller University in New York, McMaster University and McGill University, both in Canada.

Abdool Karim during a march for science in Durban.

Image: Supplied

Legacy

Abdool Karim said she hoped to leave a legacy where people believed scientific elegance was possible in South Africa and science benefited humanity.

“For me, it has always been about having a meaningful purpose in life and I am fortunate to have found it in my research in biomedical sciences and infectious diseases. Through my research I hope to inspire the future generations that science can be used to benefit humanity.

“I also believe in the importance of creating opportunities for the present and next generation, which is why we also have ongoing training and capacity development programmes for students. We are creating an environment for them to flourish and make their mark in the field of science,” she said.

Relaxation

Outside of her research in HIV and Aids, Abdool Karim said she enjoyed cooking, watching documentaries and movies, listening to music, reading and spending time with her family.

“My husband and I also make sure that we take a walk along the beach promenade as often as possible when we are in Durban. It is something we enjoy doing.”

Related Topics: