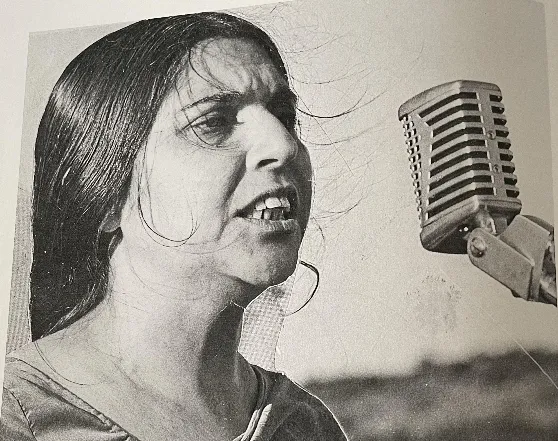

Professor Fatima Meer

Image: Fatima Meer: Choosing to be Defiant (Rajendra Chetty, 2023)

"I cannot conceive of anybody’s agreeing with all of her views, or of not disagreeing violently with some of them. But agreement and rejection are secondary: what matters is to make contact with a great soul". - TS Eliot on Simone Weil.

WHETHER with sari billowing in the wind, kaftan loosely draped, or cap shielding her from the sun, Fatima Meer was always an inspiring figure. She bred devotion, she took surprising turns in conversation, she knew her own mind, she had exquisite social graces, she was impishly naughty, she humbled herself in community meetings and, when it suited her, she cut the figure of a formidable stateswoman.

These qualities carried through half a century of resistance politics. Activist, academic, mother, wife, confidant - her life wove together disparate roles that defied any attempt to box her into a single ideology. That refusal mirrored her resistance to the sectarianism that engulfed anti-apartheid forces as they regrouped in the 1970s. It also underpinned her commitment to grounded, empirical studies through the Institute of Black Research (IBR).

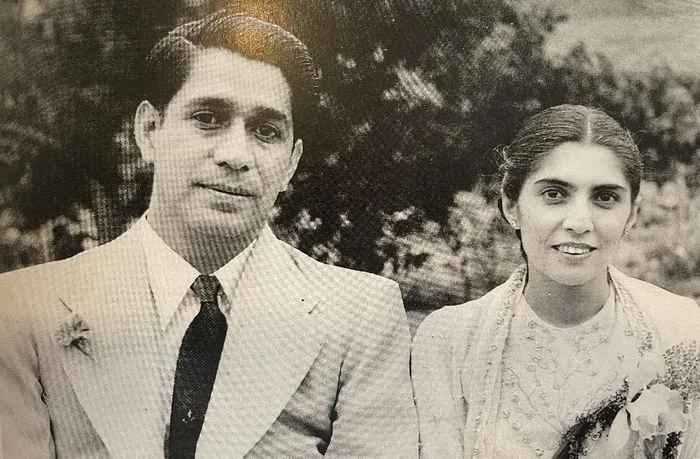

Fatima came of age in the turbulent, path-breaking 1950s. As young bride with three children, her husband Ismail faced a charge of treason.

Fatima and Ismail Meer on their wedding day on March 11, 1951

Image: Fatima Meer: Choosing to be Defiant (Rajendra Chetty, 2023)

In his biography Meer recounted in vivid detail apartheid’s knock on his door in 1956. Given an initial reprieve because he was recovering from an operation, he was kept under guard by the security police and given a few days to recuperate. At least he was prepared for his ordeal, unlike the others, who were whisked off to Pretoria without a chance to inform family and comrades.

As Ismail remembers, "the whole extended family came to see me off".

His son Rashid was too young to comprehend what was happening; his toddler daughter Shenaaz clung to him and "cried frantically"; while his elder daughter, Shamim, "was withdrawn and taut with fear". Fatima Meer "had to forcibly wrench the girls away from me as the police prepared to take me". Ismail recounted that the trial "challenged family morale. The absence of husbands and fathers told on the wives and children".

As the trial unfolded, Meer’s sixth wedding anniversary approached.

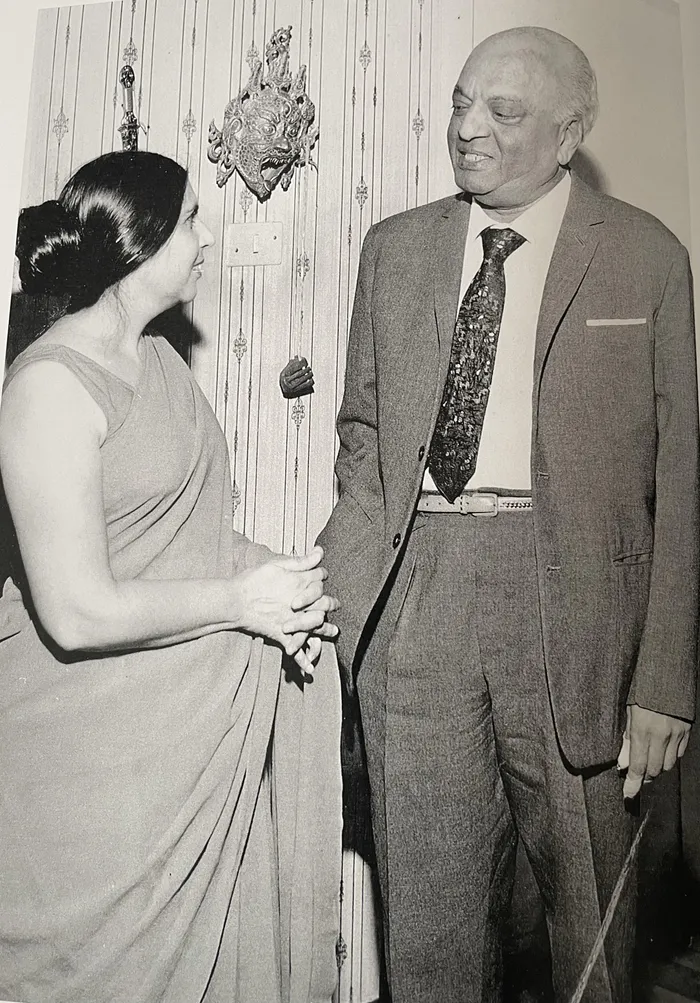

With Dr Monty Naicker

Image: Fatima Meer: Choosing to be Defiant (Rajendra Chetty, 2023)

He wrote to his wife, Fatima: "I greet you, my wife, on this day of our anniversary. The eleventh day of March is the most important day in my life, for on this day, the most beautiful woman in the world became my wife. Without her, this world and everything in it becomes meaningless. I love you. Thank you for being so patient with me. I who am such a difficult person."

Fatima Meer’s letters reflected her loneliness and longing to be with Ismail, as well as the burden of running the household alone.

She wrote to her husband in September 1957: "I am a very unhappy and lonely person. My mind is ill at ease and there seems to be no inner peace. My nails are horrible with biting. How long will life last? I know not. I ask only one thing that it should create some happiness for me. Repeatedly comments are made about my age – how old I look... At 28 I am being described as twice my age."

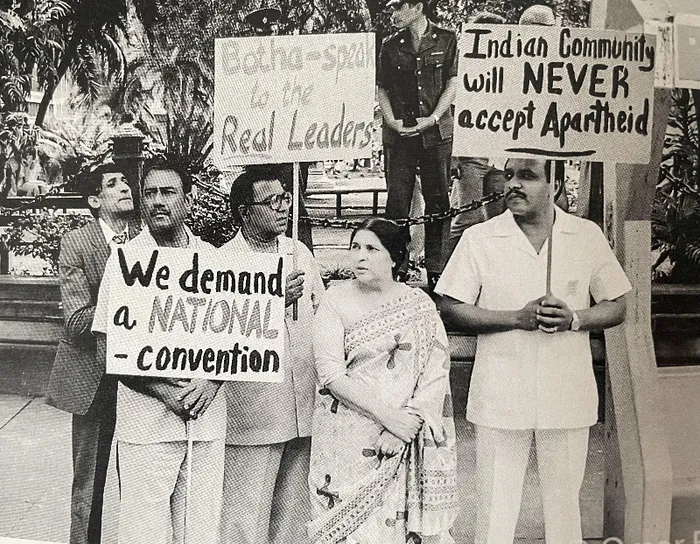

At an anti tricameral parliament protest in 1983.

Image: Fatima Meer: Choosing to be Defiant (Rajendra Chetty, 2023)

But this did not weaken her resolve: "We grow old with our idealism which remains refracted. We tend to feel shy of talking about our ideals. Yet our ideals are central to our lives. We feel strongly that this land should reflect beauty and plenty and all should reflect beauty and plenty and all her people share equally in it. Can we contribute to making this a reality? We believe we can and so we go on... Our strength is this mission and it is a strength we leave for our children."

There were tetchy moments. Fatima sent a few letters but forgot to put stamps on them. Ismail was upset. After feeling he had criticised her too harshly he wrote "I love you very much. I do not want to upset you OK?"

Fatima also complained when a week went by and she had not received a letter. Ismail immediately wrote a letter and entrusted it to Luthuli. Luthuli delivered on his promise to give it to her personally: "I was in a deep sleep… I heard a knock on the door. There were voices and the shadows of men. My heart stood still for a moment. Was it you? I was in my pyjamas, so I opened the door slightly and looked out. It was Chief; Albertina… was with him. They brought me your letter, short and hurried, but very welcome and very precious..."

What does it say about the depth of friendships and camaraderie that Luthuli, head of an organisation that was decimated by the trial, with the long trip to Groutville still ahead of him, found the time and wherewithal to deliver a letter.

One of the reasons I have used the word intimacy in the title is that I have belatedly come to appreciate its bridgehead between the political and the personal, what Manuel Tirini calls "intimate activism". It involves the "capacity to create minimal conditions for ethical and material endurance". And you see this in Fatima’s prison paintings when she was detained in 1976. Here we see illustrations of prisoners bonding, whether in the plaiting of hair or simply sitting on a stoep chatting. The more you read her prison diary, the closer you look at the paintings, the more you discern her constant sense of touch and feel.

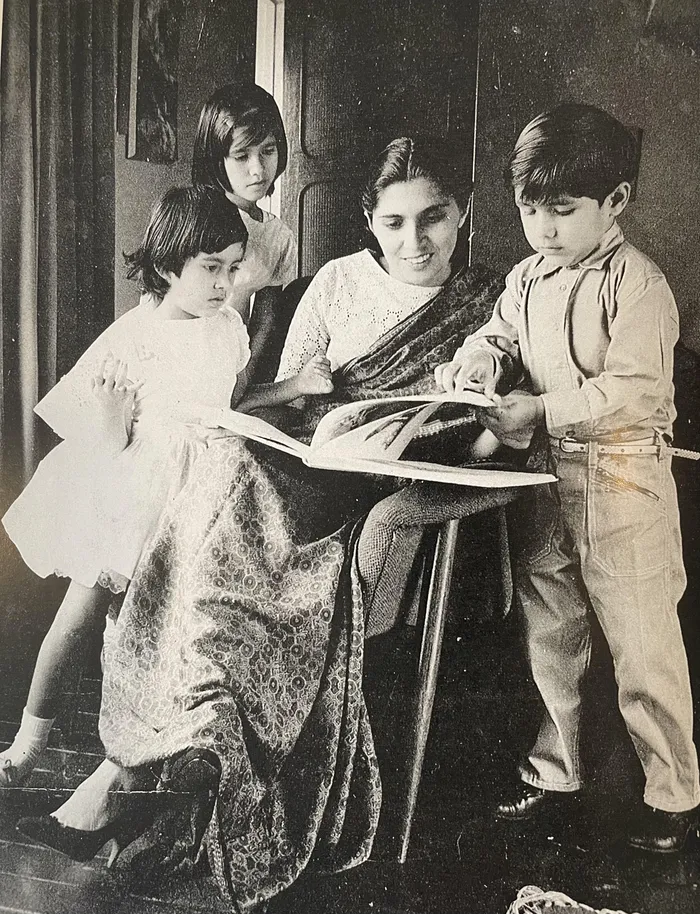

Meer and children for a Drum article on Ismail Meer's detention post the Sharpeville massacre in 1960

Image: Fatima Meer: Choosing to be Defiant (Rajendra Chetty, 2023)

The making of Fatima was the turn she took in post-apartheid South Africa. The site of this was the huge dormitory township of Chatsworth. She went there to solicit votes for the ANC in 1999. Residents told her of the new oppressors who came to evict them and disconnect their electricity and water. Moved by the poverty, especially of women in single headed households, she took on the ANC.

She was abused by members of the organisation, shunned by comrades she had spent decades in the trenches with. She responded on national television: "I have always stood by the poor and the rights of the poor. And I am standing now again for the poor... If this is standing against the ANC, then I will be standing against the ANC. Though, I must point out to you, all my friends are there. All my socialisation, all my happiness… my comradeship, for the last 60 years has been there."

She knew already "revolutionary discipline" was a fig-leaf to subvert democratic aspirations. If her actions made her a counter-revolutionary then she would embrace that label. In 2025, it’s hard to appreciate how radical this stance was. For the first time, with Nelson Mandela still in power, an ANC stalwart was involved in protest politics explicitly against his government. This was unthinkable back then and allegations of disloyalty or Third Forceism lay thick in the air. The outlier was becoming an outcast in the newly-powered and powdered ranks of the ANC.

Veteran anti-apartheid activist Professor Fatima Meer was one of many South African Indians who played a pivotal role in ending apartheid.

Image: File

Let me be frank. Fatima was no cardboard cut-out figure. She had her spots that blinded her, but that only revealed how all too human she was.

She would be acutely aware of the overarching economic policies and how these impacts on poverty and inequality. At the same time, she would have laser focussed on the corruption in which the ANC is at the vanguard.

The alibi for this theft has, scandalously, been transformation, and the rights of the people. At one level Fatima would also be thoroughly disconcerted because, when she was alive, one could still contest the orientation of the state. You could debate, lobby, organise and oppose. We now live in a topsy-turvy world where the language of redress is co-opted by construction mafias. The Guptas got a PR firm to fig-leaf their theft in the language of anti-racism. Political entrepreneurs mobilise people with lofty manifestos so that they can earn an income.

Youngsters at Wits and UCT can call Mandela a sell-out en route to cushy positions courtesy of BBBEE. Instead of penning delicate love letters, the leaders of the ANC today send lurid pics. It is almost as if the evil of apartheid imposed moral strength on people of Mandela’s generation. The danger selected only the finest for leadership. Now the loudest and those with sharpest elbows rise to the top. When Fatima was not tapped for Parliament in 1994, this was a momentary snub. In 2025, it is a reprieve from utter silliness and buffoonery.

Fatima was a bridge between the anti-apartheid struggle and the first years of activism against the ANC for dodging its promises to the poor and excluded. But I fear she would have had no luck with what goes for politics today. She had the heart and mind for it but, I am afraid, her sense of smell was too keen. She would have recoiled? Into what? Family, small community, research? Yes, but above all that, a no-nonsense scolding of all of us. For we, who were alive all this time, did not have the liver to arrest what intellectual and political life in South Africa has become.

Still. She would have continued arguing and cajoling. She would not disdain, small, incremental victories, always with an eye to creating organs of democratic power. She would have responded creatively to the ANC losing its absolute majority.

The coming of the GNU, even as it leans to the Centre-Right means that the ANC does not have a monopoly on state power. It is measured for the first time by how its ministers fare against ministers of other political parties. At the same time, it cannot just bludgeon policies through Parliament. Now they are under increased scrutiny. And the complacent cadre deployed are also under the cosh. When the ANC held the majority would you ever have had a director-deneral and deputy suspended for inefficiency?

And so, for the first time, there can be struggles not just outside and against the state, but within the state itself. And then there is the unpredictability that Trump has brought in his wake. Trumpism has created turmoil and therefore opportunity.

We of the political generation of the 1970s and 1980s who oscillate between John Berger’s undefeated despair and Lauren Berlant’s cruel optimism, must take heart from the idea that this conjuncture with its uncertainty both locally and globally, offers a glimmer.

Fatima would have approached these times with a glint in her eye. A smile of naughtiness. There was always the schoolgirl about her. In 2000 she got wind of an eviction in Chatsworth. She was recovering from a heart attack and knew Ismail would be angry if she went to Unit 3. But she went anyways, trying vainly to ignore Ismail’s phone calls. She was a scatterbrain.

Her sister Razia tells of a time Fatima was due to pick up her children. They were waiting at the gate. She came hurtling down the road in her Beetle and drove past them. And then turnaround and drove past them again. They were traumatised. Razia phoned her and asked her what happened. Fatima replied: "Oooooh, is that why I went there? I was wondering why I went out. Okay, coming right now."

Fatima came to politics when the nationalist Luthuli met the arch liberal Paton who met the Communist Moses Kotane. She always saw the value of dialogue rather than dogmatism, a refusal to have theory fossilised into rigid orthodoxy.

In the Guardian of August 30, 2025, Barney Ronay wrote the Liverpool’s right back Dominik Szoboszlai’s dummy was ‘a moment of beauty, artistry and playfulness in the middle of all that heat and noise’. Fatima was no-one’s dummy. But she was a phenomenon of beauty, artistry and playfulness even when life was under threat and hopes lay in ruins.

That is the Fatima I remember. And I hope it is the Fatima you remember too.

Ashwin Desai

Image: File

Professor Ashwin Desai, of the University of Johannesburg, delivered the keynote addresses at the Professor Fatima Meer Memorial Lecture - Leadership, activism and justice at the Howard College Theatre at the University of KwaZulu-Natal.

** The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of IOL or Independent Media.