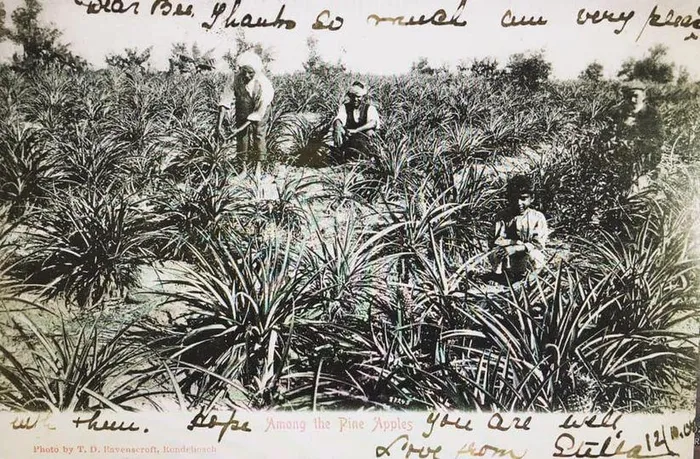

Children were often left to fend for themselves while their parents worked.

Image: Cane Fields to Freedom: A Chronicle of Indian South African Life by Uma Dhupelia-Mesthrie

CHOURI Dhorai, indentured number 98619, arrived in colonial Natal with her one-year-old daughter, Lakhrajia Timal, 98620, from Khanpur village located in the Azamgarh district of Uttar Pradesh on the Umkuzi XII from Calcutta in April 1903. The mother and daughter were assigned to the Kearsney Estates in Stanger (now KwaDukuza). Four months after they arrived, Lakhrajia was found dead, floating on the Umhlali River.

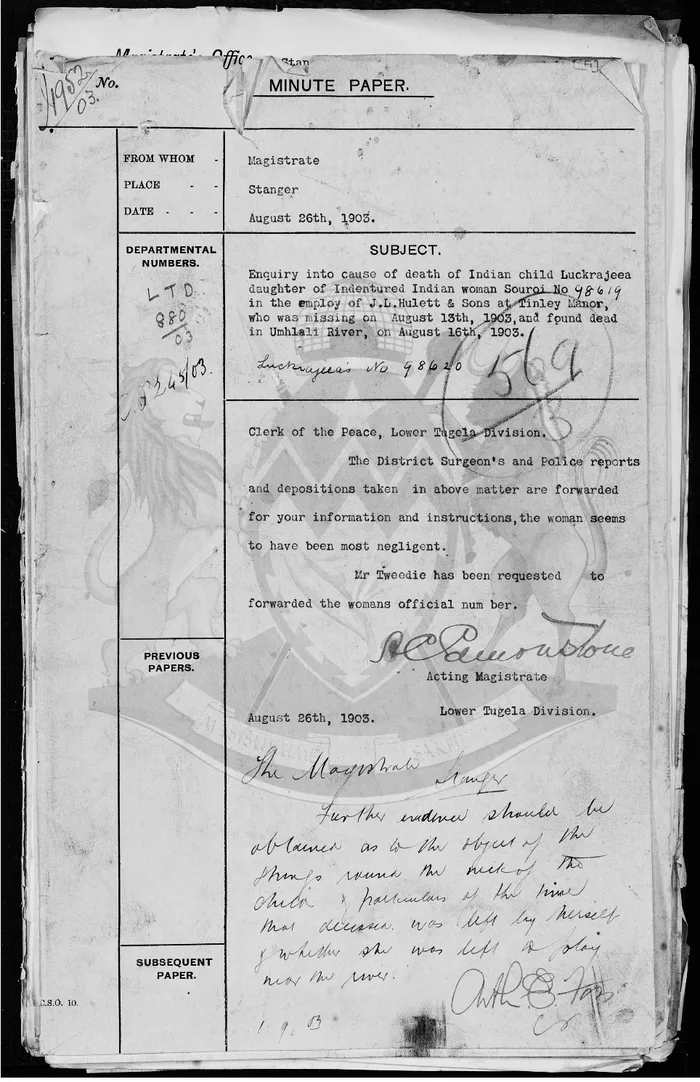

The inquisition of death file of Lakhrajia, buried in the Pietermaritzburg Archives Repository, details a range of archival transcripts that include witness account depositions to the eventual Clerk of the Peace exoneration of Chouri being negligent of Lakhrajia’s death.

The Magistrate of the Stanger district requested a full inquiry into the death of child Lakhrajia at Tinley Manor, Stanger.

John Archiebald Tweedie, a field manager for JL Hulett & Sons, stated that he knew Chouri and Lakhrajia and that he turned out a search party for Lakhrajia when she was reported to have gone missing. Tweedie went on to state that 10 days prior to Lakhrajia going missing he had seen Lakhrajia 100 meters from the barracks where the family lived.

A child with a dummy attached to his coat.

Image: Ranjith Kally

Lakhrajia was found about four yards from the water’s edge when he told one of his workers to take the child back to the barracks. Tweedie then went to the field, where he ordered Chouri to ensure that Lakhrajia was taken to the field while she worked rather than being left unattended at the barracks.

Chouri appeared before the Magistrate on August 25, 1903, stating that she arrived from India about four months ago. Lakhrajia, who was still crawling, was taken to the cane fields while she worked.

“… when I took the child to the Cane Fields, she used to crawl into the Cane, and I was afraid she would get lost in the Cane; I did lose her three times. I left my child thirteen days ago (13 August). I told two children named Juguwah and Golia aged two-and half and three years respectively, to play with my child, they were left in the barracks, my master Mr Tweedie did tell me to take the child to the field, I did not as I was afraid of losing it in the cane, I do know of any other women losing their children in the cane. I searched everywhere for my child. When I returned from the field, I did not go to the river; the spot where the body was found is a little distance from my hut. They did not go to the river the same day my child was lost. The Sidar told me that Mr Tweedie had found my child close to the river.”

In the next deposition, Cheddy, an indentured worker in the employ of JL Hulett & Sons, stated that he was instructed by the Sergeant of Police, together with other Indians, to search for the missing baby.

Minute paper of the Case file of Chouri Dhorai, indentured number 98619, who arrived in colonial Natal with her one-year-old daughter, Lakhrajia Timal, 98620

Image: Supplied

“I found the body of the child in the river Umhlali among the reeds about 30 yards from the mother’s hut… I do not know how the child got into the river. When I found the body, it was on its back and floating on the water…”

The Clerk of the Peace deposition to the Attorney General read in conclusion that: “There seems to be no doubt that the child came to its death by accidentally getting into the River. No Criminal neglect seems to attach to the woman’s action.”

The archival transcripts of Chouri and the death of Lakhrajia give us fascinating insight into the living arrangements for indentured children while their parents worked on the plantations. The plantation, owned by the Huletts, made no provision for the care of children while their parents worked in the field. Children were left in the care of other children, in the beastly barracks with no adult supervision, and carelessly left to fend for themselves while their parents worked. Children were burdens to the colonial system of indenture, whose lives were of no value. The system of indenture simply had no place for children or their well-being.

Life for indentured Indians in Natal throughout the 51 years that the system was in existence was extremely fragile. High mortality rates were prevalent throughout the entire indenture process, from the long sea voyages to the difficult period of "acclimatisation" on the plantations from 1860 to its ending in 1911.

Colonial Postcard of children in the pineapple fields while their parents worked.

Image: Professor Goolam Vahed Collection

Further insight into the fragility of life for indentured workers is found in an archival file of September 1, 1908, that reports the death of six indentured workers as a result of a “terrible accident through fire.”

“The Indian barracks caught on fire during a high wind at night as the indentured Indians were asleep before they could make their escape.”

Indenture numbers 112 905, a 13-year-old boy, 112 834, 112 835, child 112 836, and child 112 837, all perished by fire as one section of the barracks had a thatched grass roof near the storeroom.

Other causes of death among Indian indentured workers included infectious diseases, exposure to cold, malnutrition, and violence, all exacerbated by the brutal living and working conditions on colonial plantations. Analysing the Protector of Indian Immigrant reports on the death of indentured workers, through my ongoing research, from 1876 to 1912, shows that 35 650 or 31% of the total population of indentured workers, making up 114 271 by 1912, had perished either on their voyage to Natal or on the plantations.

The average death rate hovered around 16.78 per 1 000, with the last decade of indenture to Natal from 1901 to 1911 proving to have the highest mortality rates, with an average of well over 20.28 per 1 000, with the year 1906 and 1907 proving to be the deadliest, with 25.61 and 23.25 per 1 000 indentured workers, an astonishing 2 611 and 2 392 people respectively having died in those calendar years.

Unnatural deaths were reported as a separate annexure for each Protector report. High among the categories of unnatural death were attributed to being burned to death and suicide. Other causes that were reported included being run over by wagon wheels, drowning, like that of Lakhrajia Timal, murder by skull fracture, children being overlaid in bed by parents, trolley accidents on the railways, snake bite, excessive Isangu (marijuana), and alcohol poisoning.

Sadly, almost half of all those deaths recorded each year were recorded as being children under 10 years of age, the majority of whom were burned to death in their hut or in the sugar cane fields.

Brutality and violence lay at the core of indenture. Perhaps the most extreme evidence of psychological trauma is the high rate of suicide on the plantations. The Indian Opinion (a newspaper published by Mohandas Gandhi) of June 4,1904, called for a commission of inquiry into the matter, but none was ever appointed. There are hundreds of medical and employer reports in the Indian Immigration records in the Natal Archives on individual cases of suicide.

By 1903, according to statistics sourced from the Public Protector records, out of the free Indian population of 51 259, there were 8 suicides. Out of 30 131 indentured Indians, there were 23 suicides. At the same time, the highest rate of suicide was found in Paris with 422 suicides per one million people. The rate among the indentured Indians, however, was far worse and came in at 741 suicides per one million people.

Revisionist historians toy with suggestions of people leaving their homes in search of a better life, and indeed, some finding that in the colonies. While there may be some merit in those assessments, experiences varied. The records demonstrate that Natal was among the most violent and vicious in the treatment of indentured workers – rape, floggings, murder, denial of food and earnings, and codified racial discrimination.

We part company with both the revisionists as well as the apologists for imperialism and its great “civilising” mission. Our bias is in telling the stories of the (in)human exploitation of the working people from whom we are descended. As we commemorate 165 years of the first indentured workers arriving in Natal on November 16, let us be well aware of telling the full account of the experience of indentured life in Natal, knowing that it came with extraordinary sacrifice and the incredible loss of life.

Selvan Naidoo

Image: File

Selvan Naidoo is the great-grandson of Camachee, indenture number 3297, and Director of the 1860 Heritage Centre.

Related Topics: