Tracing the footsteps of indentured workers in Port Shepstone

Untold stories

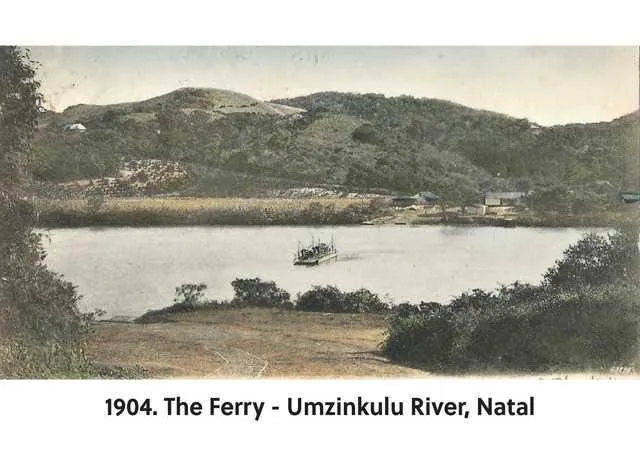

Ferry on Umzimkhulu in 1904 with indentured worker accommodation on the river bank)

Image: SUPPLIED

PORT Shepstone lies about 120km south of Durban, along a route that crosses 23 rivers before reaching the mighty Umzimkhulu. The town forms part of the area between the Umzimkhulu and Umtamvuna rivers, which was annexed to the British Colony of Natal on January 1, 1866.

The Port Shepstone Twinning Association, a local NGO dedicated to heritage work, has uncovered a remarkable history of Indian indentured workers in the region. Using archival records of 152 184 indentured workers in Natal, the organisation compiled a detailed list of those assigned to work in Port Shepstone between 1876 and 1911.

The study found that 3 307 individuals were indentured within the Port Shepstone community alone, a figure that highlights the town’s significant role in the broader history of indentured labour in South Africa, especially in the development of the agricultural economy.

Of those workers, about 612 returned to India after completing their five-year contracts, while 30 died during their indenture period. These findings are documented in Umlando Wethu, Our History, which was launched in Port Shepstone on September 20 this year. The event featured keynote addresses by Professor Ashwin Desai and Professor Paulus Zulu, with memorable music by Professor Chats Devroop. Kiru Naidoo was the launch facilitator.

The compilation was drawn from records of 21 employers in the district. Among them, the farm Barrow Green, belonging to Colonel JJ Bisset, employed approximately 2 776 workers, followed by Ruthville Estate with 151, while smaller farmers employed the remainder. Others were indentured to individual families. In addition, a number of workers who had originally been indentured elsewhere chose to settle permanently in Port Shepstone after completing their contracts. This helped lay the foundations of a vibrant local community whose descendants remain part of the area’s rich heritage.

Archival records reveal 30 deaths in Port Shepstone.. Twelve individuals were recorded as deceased from natural causes, and sixteen deaths resulted from accidents or violence, including exposure, starvation, burns, and falls into boiling sugar. Suicides and unexplained deaths also point to mental strain and systemic neglect. Tragically, two workers indentured at Barrow Green, Munian Kali (“Coolie No”. 74,988) and Subban Mari (“Coolie No”. 75,054), were executed in 1904 and 1905, respectively. Both arrived from Madras in 1898, but the reasons for their executions remain unknown, highlighting the need for further research.

In 1876, 19-year-old Dowlutia Jhingoor arrived in Port Shepstone as an indentured worker. For six years, until the next group of workers arrived in 1882, she may have been the only young Indian woman in the area. Likely assigned to work in a household, one can hardly imagine what life must have been like for her, being the sole Indian in this area, and a woman.

In November 1897, Prudasy Pinagadi (Coolie number 69732), 27, arrived with his wife, Sinnasamma, and four children. Assigned to work as a head boiler, his five-year contract was abruptly ended in 1902 after he was found guilty of “flagrant misconduct”. His punishment was to return to India immediately.

Tragedy struck another worker at Barrow Green, Kola Ramadu (Coolie number 69396), who also arrived in November 1897. Just a year later, he died after falling into a vat of boiling sugar juice, a stark reminder of the extreme dangers faced by indentured workers.

The £3 poll tax, imposed under Law 17 of 1895 in the Colony of Natal, targeted Indian indentured labourers who had completed their five-year contracts, and chose not to re-indenture or return to India. It applied annually to men, women and later to children over the ages of 13 and 16, placing a heavy financial burden on families already earning meagre wages.

The tax was designed to pressure ex-indentured Indians back into plantation labour or force them out of the colony altogether. For most, it was impossible to pay, as average monthly earnings were less than £2. Failure to comply led to court appearances, fines, imprisonment or deportation. Desai and Vahed, in their book, Inside Indenture, capture one story that reflects the harshness of the tax.

Poonamah Ponusamy (71697) arrived from Pondicherry in March 1898 at the age of 18 and was assigned to the Umzimkhulu Sugar Company in Port Shepstone. She completed her indenture in 1903, but struggled to make a living. On February 14, 1906, she was ordered to pay £6 in outstanding tax in instalments, but could not. Appearing before the magistrate at Lower Umzimkhulu, she was declared indigent, and the Protector of Immigration arranged for her return to India. At age 26 she was sent back, destitute.

For many indentured workers, education became the key to freedom, empowerment and social advancement. Within their communities, schools and learning initiatives emerged as powerful tools for self-improvement and progress. In Port Shepstone, education took root long before formal schooling became widely accessible. While missionaries introduced early education, their efforts later faced closure. In 1926, the local community rallied together and formed the Port Shepstone Hindu Education Society, determined to secure continued access to learning. Their efforts led to the establishment of educational institutions built through unity, sacrifice and a shared belief in education as the foundation of a better future.

It is believed that the first large compound for indentured workers in the area was on the south bank of the Umzimkulu River (see photograph), less than a kilometre from what later became the Umzimkhulu Sugar Mill.

The Indian community over time grew into several other areas including White City, Albersville and Marburg. In latter years there also developed several significant communities of small farmers or workers in areas such as Louisiana, Band Farm, Langalibalele, Izotsha, Oatlands, Paddock and Hibberdene

This model of community-driven education was not unique to Port Shepstone. Across the South Coast, similar grassroots efforts led to the establishment of educational facilities, serving as evidence of the leadership and vision of early Indian migrants who viewed education as a path to dignity, equality and progress. Across the region, similar efforts gave rise to several schools, founded through local sacrifice and leadership. Some of the schools were: Port Shepstone Government Indian School, Port Shepstone Primary School, Jai Hind Primary School, Umzimkulwana, Oatlands, Parukville, Louisiana, Port Shepstone Indian High School, EP Moodley, RA Engar School, Marburg Secondary School (land purchased from ML Sultan Trust), and Woodgrange-on-Sea School.

These stories of hardship and hope, of courage and endurance form part of a much larger narrative of Port Shepstone’s early history. Their contributions to agriculture, community life and education laid the foundations for generations that followed. Their footsteps remain embedded in the soil of the South Coast, a reminder that from indenture emerged identity, and from adversity, a lasting legacy of strength, unity and hope.

Gulshera Khan

Image: SUPPLIED

Khan is a retired social worker, heritage activist, and one of the founding members of the Port Shepstone Twinning Association. She is a descendant of indentured workers. She compiled and edited the book titled Umlando Wethu-Our History: Sites and Stories through Time Travel and Applied Heritage. The book has 14 chapters covering diverse local community histories - including indenture, forced removals, missionary work, the 1906 Rebellion in Umzumbe, the poll tax and the development of local education.