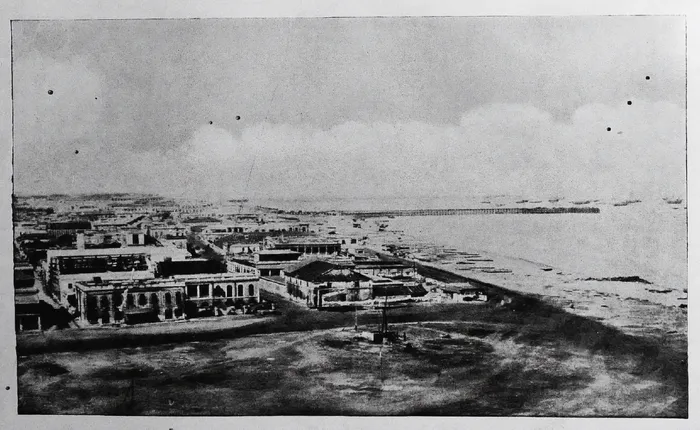

Chennai Port, now a restricted site, where millions of indentured workers left for Natal, Ceylon, Malaya, and other imperial colonies hungry for labour

Image: Supplied

THE indentured labour system became part of the new imperial economy of the 19th and 20th centuries, transporting indentured workers from India and China to the Mascarene Islands, the Caribbean, the Americas, Africa, Southeast Asia, and Australia. These workers formed a new labour force and must be credited for building the modern economies across the new world.

After close to 76 years from when indentured labour was first implemented in Mauritius in 1934, the Sanderson Committee, a British government committee, was commissioned in 1910 to explore the future use of Indian contract migrants in colonial environments.

According to Professor Ulrike Linder, the Sanderson committee mentioned the “invaluable service” of Indian immigration in many colonies of the British Empire and proposed encouraging the introduction of indentured labourers in the future. So valuable was this service that Professor Linder highlighted the use of indentured Indians in lesser-known imperial colonies, like that of the German colony of South-West Africa by the Lüderitz Bay Chamber of Mining in 1910.

Ruined buildings located at the former indentured depot, now located at the site of the Communicable Diseases Hospital in Tondiarpet, are located on a 14-acre plot, 3km from the Madras Port.

Image: Supplied

Despite this spread of labour across the world, the history of Indian and Chinese indenture remains unknown to the world, with very little being told even in the place of its source. One way we can remember these sites and, in turn, keep memory alive is to memorialise sites of conscience where indentured labour was administered.

In Chennai, to the south of India, Tamil migration to develop the new world in the 19th and 20th centuries formed the largest regional component of Indian emigration during the colonial era. More than 1.5 million ethnic Tamils from south India were listed in 1931 in other (mainly British) colonies where they had poured in during the previous one hundred years. A typical feature of Tamil emigration was the "kangani" system in which labour recruitment from India and supervision on the plantations were in the hands of Tamil headmen. Tamil workers were sent mainly to the newly-developed plantations, but they were also active in the urban economy.

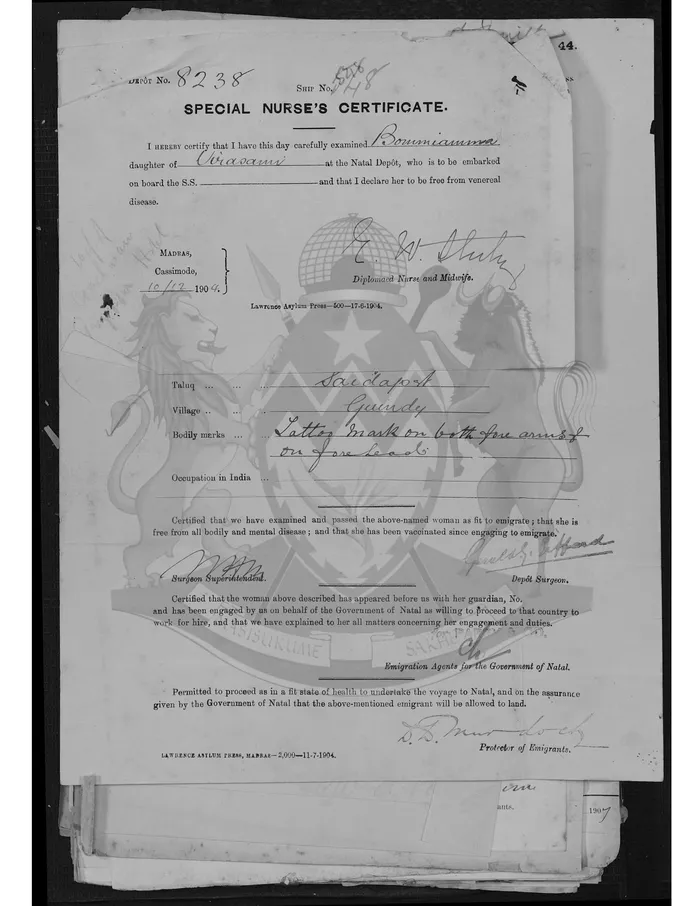

A Special Nurse certificate passing an indentured worker as safe for passage done at the Cassimode (Kasimedu) Indentured Depot.

Image: The Pietermaritzburg Archives Repository

The process of recruitment (for indentured workers) was highly formalised. An agent (arkatia) went about collecting prospective workers from nearby villagers who were brought to emigration depots from where they became imperial subjects of the Indian Protector of Emigrants. Here, they were medically inspected and made to wait for up to three months for the ships to take them to their respective colonies.

In Madras, the emigration depots were located at Cassimode (Kasimedu) and Tondiarpet.

Cassimode (Kasimedu) is a fisherfolk town, occupied by generations of families who depend on the fishing harbour and the fish market nearby. The Kasimedu Indentured Immigration Depot was a critical, albeit painful, historical site located near the Madras (now Chennai) Harbour in Tamil Nadu, India. It served as a primary holding centre for Indian indentured labourers who were transported to British colonies, most notably Natal (South Africa), between 1849 and 1923.

On January 20, 1906, a report on the indigenous plague in Madras, titled Plague in the city of Madras, by TS Ross, IMS Captain, Health Officer, Madras, highlighted the Natal, Fiji, and Mauritius emigration depot from where a dead rat was thrown, causing the spread of the disease. The report described the location and physical conditions of the depot, revealing that:

“The village consisted of 118 huts with a population of 613, and was situated on the sea coast, with immediately on its rear the Mauritius, Fiji Emigration Depot enclosed on three sides by high brick walls… On the road between the village and the depot wall, a dead rat was found on 22nd January, and on passing the same spot about two minutes afterwards, another rat, some time dead, was found, having evidently been thrown there by someone, most likely from inside the Depot.

"Enquiries were at once made of the Depot Superintendent, and he admitted that rats had been dying within the depot, but he did not know of what cause, or how they were disposed of… The depot was at once evacuated, though strangely enough no human plague cases were ever reported from amongst the emigrants with whom the depot was, at the time, crowded.”

Gopinath Krishnamurthy, Vice Chairman of Welcome Travel And Tours, Chennai, walks in Cassimode (Kasimedu), a fisherfolk town occupied by generations of families who depend on the fishing harbour and the fish market nearby. The Kasimedu Indentured Immigration Depot was located at this site.

Image: Selvan Naidoo

The other indentured depot, also to the north of Chennai, is presently located at the site of the Communicable Diseases Hospital in Tondiarpet, set on a 14-acre plot, 3km from the Madras Port.

According to an article titled "The Lost Landmarks of Chennai" in Madras Musing, the first structure came up in the 1840s and was rebuilt in the 1850s.

“It was divided into sections, based on the country of emigration, namely, Mauritius, Fiji, Natal, Malaya, etc. There was a cooling-off period before indentured labourers embarked from here. This was to enable family members to come and claim back those who had run away from home! The structures were described as more of a stockade than a building; it was, so several inspection committees claimed, airy and well-ventilated, though it is a moot point if any of the inspectors would have cared to live in any of these spaces.”

Dare House located at Parry’s Corner, Chennai. Located at No.2, NSC Bose Road, Parry’s Corner, Dare House became the place that housed the agents responsible for the recruitment of indentured labour.

Image: Selvan Naidoo

Old Picture of Parry’s Corner in 1931.

Image: Supplied

While the administration of the migrants and their eventual transportation was the responsibility of the government, it depended on a whole host of support services provided by the British companies of Madras. They were involved in almost every aspect, from recruitment, for which they had agents, to sending the labour out, as they held agencies for various transnational shipping lines.

One of the largest agencies in charge of bringing indentured labour to former imperial colonies was Parry and Company. Located at No.2, NSC Bose Road, Parry’s Corner, Dare House became the place that housed the agents responsible for the recruitment of indentured labour. Parry & Company became the official agent for the Natal Shipping line, which operated through depots (like Tondiarpet), recruiting from South India (Tamil Nadu) for colonies like Natal, Reunion, Martinique, Mauritius, Fiji, etc, offering contracts for plantation work.

An aerial view of Parry’s Corner. Its close proximity to Chennai Port made it an ideal trading company location for recruiting indentured workers.

Image: Hilton Brown, Parry’s of Madras, A Story of British Enterprise in India.

The company was started by Thomas Parry, who arrived in Chennai in 1788 as a young Welshman who had completed a five-month, tedious sea voyage. Parry worked as a "free merchant,” permitted by the East India Company to enter the Madras Presidency, working from Fort St George. The company did not like the free merchants, complained bitterly about their competition, and annoyed and harassed them in a variety of ways, only allowing a license to a few of them because there was a considerable volume of trade that the East India Company could not handle itself.

Years after Thomas Parry had died, Henry Nelson, a partner for Parry & Company, questioned the government on why the same emigrant ships that take 450 emigrants from Calcutta and 500 or 600 from Bombay, but only 350 from Madras? If the French deemed 60 cubic feet per emigrant from their Indian possessions a sufficient allowance, why did the British Government insist on 72? The government thankfully replied that they had no intention of abandoning rules which tended to secure the health of their subjects.

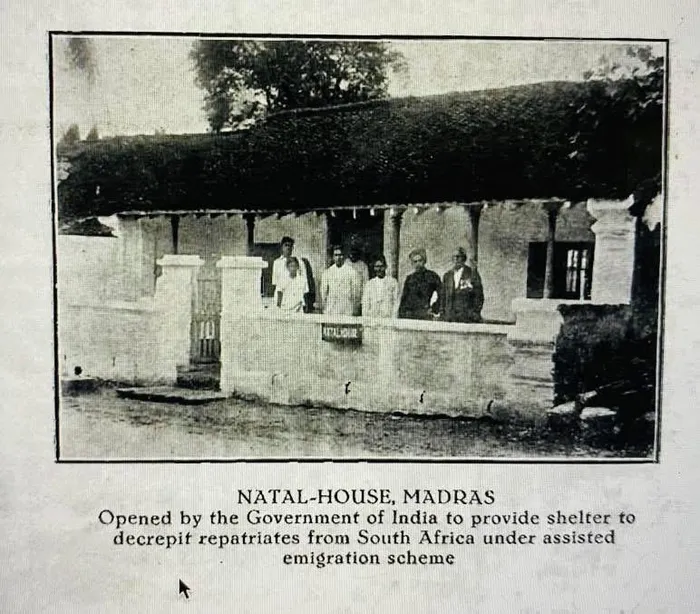

The Natal House Madras was established at a location called 89 Brodies Road, Mylapore, Madras in 1929 to cater temporarily for the Indian returnees.

Image: Bhawani Dayal Sannyasi and Benarsidas Chaturvedi, Emigrants Repatriated to India under the Assisted Emigration Scheme from South Africa, and On the Problem of Returned Emigrants from All Colonies.

In the 20th century, Parry & Company turned their business interests to handling a flow of returning emigrants homing from South Africa to India at the close of their indentured periods.

Professor Uma Dhupelia Mesthrie’s seminal research on returning emigrants to India under repatriation revealed that the returning emigrants were housed at “the Natal House established at a location called 89 Brodies Road, Mylapore, Madras in 1929 to cater temporarily for the Indian returnees. The house hosted the old, decrepit, and hopeful job-seekers, and there were many a sad soul that occupied those quarters despite the efforts of the kindly official appointed to assist them".

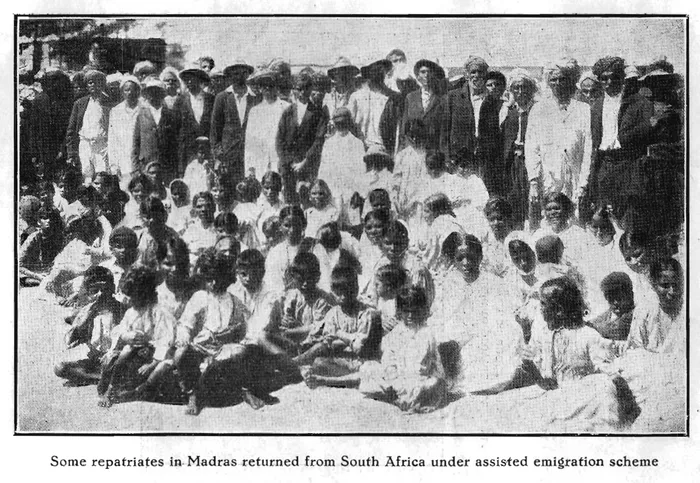

On May 15, 1931, a report on the Emigrants Repatriated to India under the Assisted Emigration Scheme from South Africa and On the Problem of Returned Emigrants from All Colonies was authored by Bhawani Dayal SannyasiBenarsidas Chaturvedi.

Some repatriates in Madras returned from South Africa under the assisted emigration scheme.

Image: Bhawani Dayal Sannyasi and Benarsidas Chaturvedi, Emigrants Repatriated to India under the Assisted Emigration Scheme from South Africa, and On the Problem of Returned Emigrants from All Colonies.

The report revealed the horrible conditions that awaited returning indentured workers in both Calcutta and Madras. Testimony included the plight of many returning emigrants, like that of “Saubhagyam, a young girl who was born in Natal, came away from South Coast Junction with her husband and a child of one year. The child died soon after their arrival in Madras in 1928. The husband also died shortly afterwards. Now she was all alone, the bonus money had been almost spent, only 13 Rupees remaining out of it. Her relations in Natal were trying to get her back there. Whether they succeeded or not is not known to me (Bhawani Dayal Sannyasi)".

Another returning indentured worker, identified only as KM from May Street in Durban, was “tempted by the assisted emigration scheme and came away with his wife, one son, and six daughters. He had Rs 2 000 at the time of his arrival, all of which has now been spent. He has not been able to get any employment. He has taken to the profession of begging, and there, too, he has not been a success. He wrote a letter to his friends in Natal on behalf of his wife, informing them of his own death! His object was to excite the pity of his friends and get their help. It is said that his friends in Natal issued an appeal for his widowed wife!

A ruined building located at the former indenture depot in Tondriapet.

Image: Selvan Naidoo

Bhawani Dayal Sannyasi went on to conclude that the Natal House, which could accommodate only 15 people at the most, was a sorry sight to behold. He was sorry that he could not visit the districts of the Madras Presidency, but what he had seen of these repatriated people in the City of Madras and what he heard from them was sufficient to convince people of the folly of repatriation. At present, the exact location of the Natal House, previously located on 89 Brodies Road, has yet to be determined.

An important site of conscience in mapping indentured labour routes, the Chennai Port, now a restricted site, where millions of indentured workers left for Natal, Ceylon, Malaya, and other imperial colonies hungry for labour. Like the Kolkata Memorial of Indentured Labour that stands at the former Kidderpore Depot (near Jetty No. 8) along the Hooghly River, honouring over one million Indian indentured labourers, it would be honourable of the Tamil Nadu government to erect a similar memorial in tribute to the 1.5 million indentured workers who left from the Chennai Port.

In mapping these indentured sites of conscience in Chennai, detailing their location and historical significance, the story of indenture will forever be memorialised in keeping alive the memory of all those indentured workers who left India to help shape modern economies across the world.

Selvan Naidoo

Image: File

Selvan Naidoo is the great-grandson of Camachee, indentured number 3297, and Director of the 1860 Heritage Centre.

Related Topics: