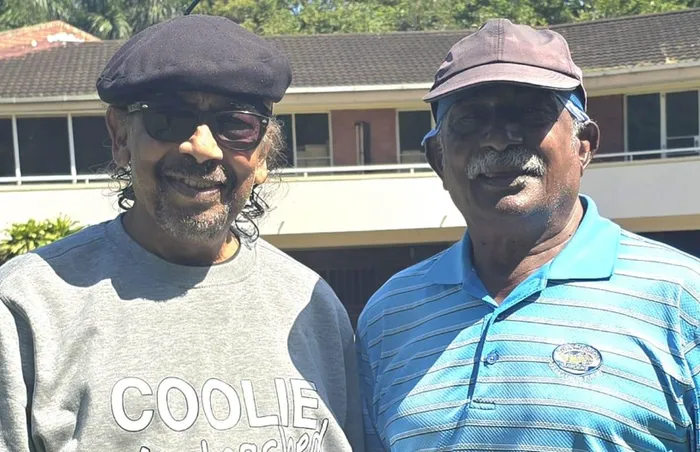

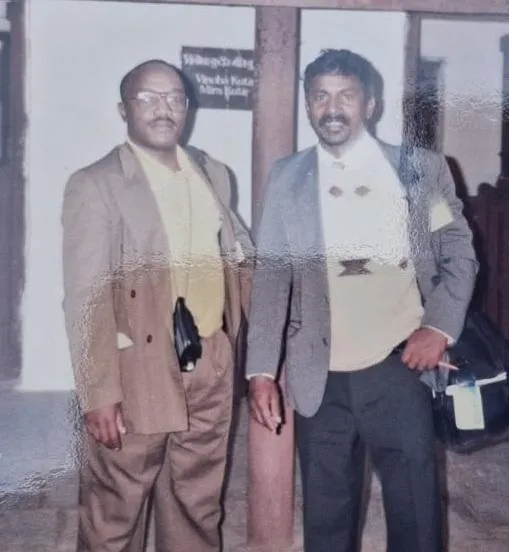

Veteran struggle-journalist Marimuthu Subramoney, also known as “Subry Govender”, right, recently released his first book, an autobiography, “Coolie Journalist”. He is seen with internationally-acclaimed cartoonist, Nanda Sooben.

Image: Supplied

AT age 79, VETERAN journalist Marimuthu Subramoney, also known as 'Subry Govender', has documented South Africa's struggle against apartheid despite surveillance, detention, and banning orders.

In his new autobiography 'C***ie Journalist', Subramoney, recounts how his humble beginnings led to a career giving voice to the oppressed, covering Nelson Mandela's release and presidency, and becoming a target of the security police.

His story reveals the critical role journalists played in fighting for South Africa's freedom.

A young Subramoney with his parents, Salatchi Munien and Subramoney Munien.

Image: Supplied

Subramoney, who lives in Umdloti, said he was a third generation indentured descendant from his maternal family.

His maternal great-grandparents, who were from a village in Tamil Nadu, in India, arrived in South Africa in the early 1880s.

“When they came to Natal, they worked at the Blackburn Sugar Estate, near Mount Edgecombe. After their 10 year indentureship they were recruited to work for a white family and moved to Ladysmith - with their two daughters; my grandmother and her sister."

He said during this time, his family experienced a traumatic incident. His grandmother and her sister nearly lost their lives after they were washed down a flooded river. They were saved by a man who was passing by and noticed the young girls in trouble. He jumped into the fast-flowing waters and saved them from drowning.

“However, after the ordeal, the family returned to Natal, and lived in the Congella Barracks, before moving to Clairwood. At around the age of 11, my grandmother was married and had 14 children, of which 11 survived. My mother, Salatchi, was one of six daughters.”

Subramoney said his paternal great-grandparents were also indentured labourers.

“They lived in the Magazine Barracks, and later moved to Cato Manor. My father, Subramoney Munien was one of nine children. My parents' marriage was arranged, and they settled in Cato Manor. My father worked as a labourer, while my mother worked as a domestic helper. She later worked as a machinist for a clothing factory,” he said.

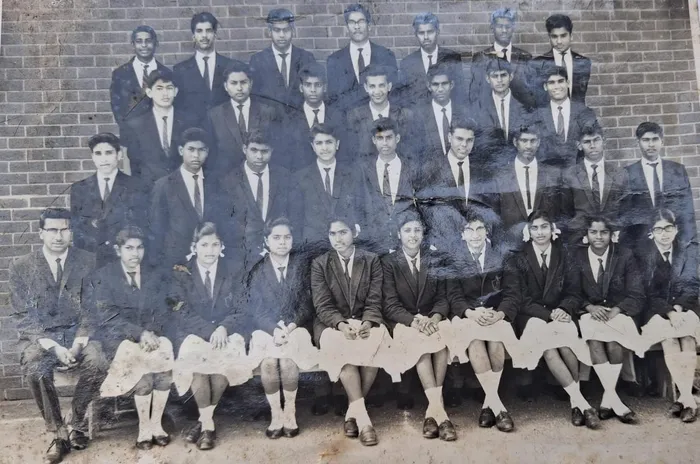

Subramoney, back row, far left, in matric at Verulam High School in 1965.

Image: Supplied

Subramoney, who was born on December 15 in 1946, said the family moved from Cato Manor to Isipingo when he was still quite young.

“At that time, it was just my elder sister and I. Our entire family lived in a small room, there was no space. So we moved to Isipingo. Later on, our other five siblings were born.

“I have some very fond memories of growing up in Isipingo. We used to play soccer on the grounds, or go fishing and swimming in the river. We had hours of fun, even though we did not have much, we enjoyed life.

“When I was about nine years old we moved to Munn Road in Ottawa. Those were the best days of my childhood. We experienced the real sense of the term, community. We were not neighbours. We were a family. The community took a great interest in looking after one another. One of the best memories is celebrating each other's festivals, be it Christmas, Deepavali or Diwali, and Eid. We always spent those special days together,” he said.

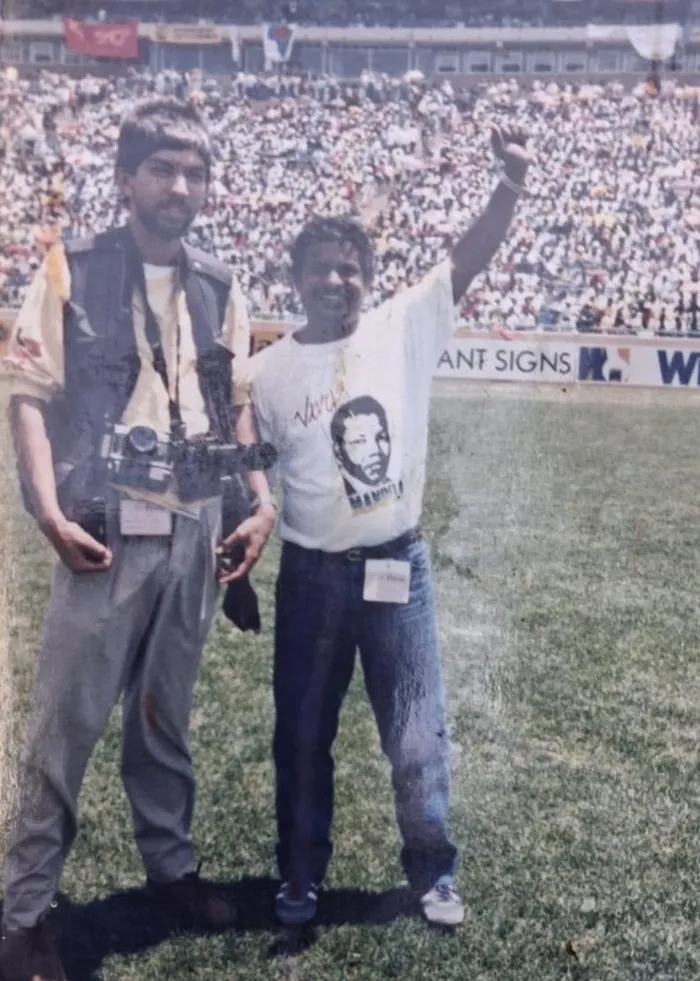

Subramoney, right, while covering the mass rally that the late former South African president Nelson Mandela addressed at after he was released from prison in 1990.

Image: Supplied

Subramoney said as a child he also worked on a sugar estate, which sparked his passion to be a voice for others.

“During the school holidays, my father said he did not want me to sit at home and do nothing. He said I should try to find a job. I was in Standard eight at the time. My two friends and I found jobs as cane weeders at a sugar estate in Ottawa. I remember on the third day, we heard the supervisor shouting at some of the women. I could not understand why he was doing that, so I went up to him and asked him.

“He started shouting at me, and asked who I was to question him. I asked him why he could not speak to them decently, to which he responded that if I did not want to work there, then I must get out. I did not think twice, I left, and so did my friends. From then, I noticed the difference in the way people were treated. I did not like it, and neither was I going to stand for it,” he said.

Meeting Nelson Mandela.

Image: Supplied

Subramoney said he attended Isipingo Primary School from Class one to Standard three. When the family moved to Ottawa, he attended Jhugroo Primary School from Standard two to six.

He went on to complete his matric at Verulam High School in 1965.

Subramoney said it was during history lessons that he learnt about the oppression in the country, and the impact on its citizens.

“My history teachers used to speak a lot about the situation in the country. I didn’t understand the gravity of it at that point, but things that happened later on would spark my interest in pursuing a career where I could be a voice for those that were being impacted, even as far as sharing them with news outlets abroad, which would later land me in hot water with the security police.”

He also enjoyed playing cricket and soccer.

“I played for the school team, and for a local club.”

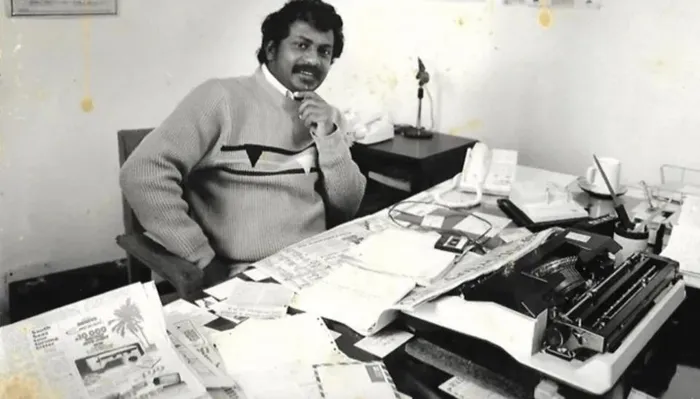

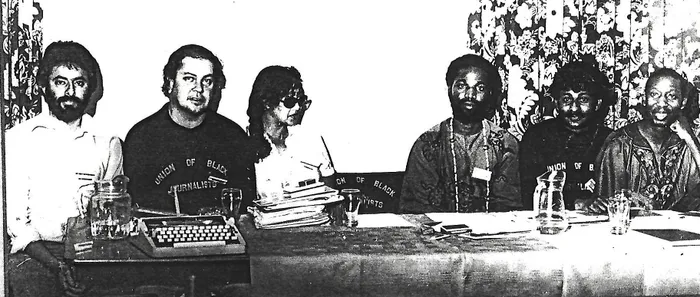

While heading the Press Trust of South Africa, an independent news agency in the mid-1980s.

Image: Supplied

Due to his parents being unable to afford to pay for his further studies, he decided to get a job.

“I wanted to study for a Bachelor of Arts degree, but due to the lack of finances, it was not possible for me, so I got a job as a clerk for an insurance company. However, during this time I was also working as a freelance-journalist, writing sport and community news articles for the Daily News and the then-Golden City POST.

“However, after about three years I was fired after I had written an article and submitted it for publishing in the company’s magazine. The article was focused on 'why was motor insurance for whites cheaper than for blacks?'.

“Shortly after submitting the article, and before it could be published, my manager called me aside, and asked why I was causing problems in the office. I was then fired.

“I started working at another insurance company shortly after. However, just a short while into the job, I received a call from the news editor of the Daily News. He told me there was an opportunity for me to work as a full-time journalist. I immediately put in my resignation, and joined the Daily News in 1973,” he said.

Subramoney, second from right, was a national executive member of the Union of Black Journalists. The union was banned in 1977.

Image: Supplied

Subramoney said he soon became a target of the security police.

“I was writing on non-racial sport and politics, as well as the impact of apartheid on citizens. The security police were not happy, and even inquired from my white colleagues, ‘Who is this C***ie journalist?’. They made my life difficult. They tapped my phone and monitored my correspondence such as letters received. They even raided my house and desk at the office. I was subjected to ongoing harassment and intimidation. I was also detained for six days after writing an article about school boycotts.”

Subramoney said during this time he was also working as a foreign correspondent for various radio stations including BBC, Radio Deutsche Welle, Radio Netherlands and Radio France Internationale, as well as the Press Trust of India, a news agency.

While covering the official visit of Nelson Mandela to India in 1995. He is seen here with a fellow SABC colleague outside the first home of Mahatma Gandhi in Gujarat.

Image: Supplied

During this time, he played an instrumental role in the formation of the Union of Black Journalists.

“It was founded after the Soweto Uprising in 1976. However, we were banned a year later.”

After he left the Daily News in 1980, he embarked on a new project, the establishment of a newspaper, Ukusa.

“I was working with prominent anti-apartheid leaders to establish a Black newspaper. However, in December 1980, I received a three-year banning order and was put under house arrest. They did not like that I was working as a foreign correspondent. I was 'painting a bad picture' of the government in South Africa.”

Subramoney said during this time, he completed his Bachelor of Arts degree, majoring in political science and international relations.

He also established the Press Trust of South Africa, an independent news agency.

Subramoney said after the banning order was lifted after two-and-a-half years, he began working again as a foreign correspondent.

“I was working even harder for the BBC and radio stations around the world, from the US to Canada, Australia, and Singapore, among other places. I was their official correspondent in South Africa from 1983 to 1994,” he said.

Subramoney said he was approached by the SABC to be their senior political correspondent in 1994.

He held the position until his retirement in 2010.

He thereafter returned to being a foreign correspondent for international media outlets, mainly Radio Deutsche Welle until 2023, when he retired from the media industry.

“During my career, I covered the release of Nelson Mandela, to him being elected as president, and later his visit to India. I had the opportunity to interview him. I covered his death, travelling from Durban to Johannesburg, and then to his hometown. I also covered former president Thabo Mbheki’s visit to India.

“I had the opportunity to interview some great people such as the now late anti-apartheid activists, Fatima Meer for her 80th birthday, and Ahmed Kathrada upon his release from prison. I travelled to Mozambique when the South African and Mozambican government entered a truce, and signed a treaty not to attack each other. These are some of the highlights throughout my career, ” he said.

As a struggle-journalist, he faced many challenges.

“There were several incidents. After I completed my studies, I was offered a two-year scholarship to do my postgraduate studies at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland. I was denied my passport for 10 years. The South African government refused to give it to me as I was a 'C***ie journalist that supplied overseas people with news about South Africa, which discredited the government'. I was also offered a one-year contract at Radio Deutsche Welle but could not go. There were many opportunities that I missed out on because I spoke to the truth.

“However, it did not deter me, instead, it motivated me to work harder, and keep highlighting the conditions under which people lived. I wanted to ensure that as a journalist, I worked in such a way that helped the people. I believe I achieved that in my career."

Subramoney said he was inspired to write his autobiography to showcase the important role journalists played during apartheid.

“We ensured that we highlighted what was happening in the country; the harsh reality of what people faced. I felt that would be something that the younger generation should read and learn about so they know the sacrifices that were made. It was not easy for us; we endured a lot.

“I am now working on another book which is a compilation of the interviews I have done with people who fought for the freedom enjoyed today,” he said.

Subramoney said media freedom in the new democracy should not be tampered with.

“Without freedom of speech and freedom of the media, democracy would not survive in the new South Africa. This is the legacy that I would like to leave behind for journalists. I also hope to inspire them to make a contribution to social, political and economic development which will make a difference for the better in the lives of the people and society.”

He is married to Thyna Subramoney for the past 52 years, and they have three children; Kennedy Subramoney, 51; Seshini Naidoo, 48; and Nomzamo Zondi Subramoney, 35. They have seven grandchildren.

Subramoney said he enjoyed playing golf three days a week and travelling. His next trip would be to Malaysia and India.

Related Topics: