Budget’25 - needs of the people in the balance with economic challenges

The column explores some of the key aspects of the 2025 Budget, the reasons for its delay, the political dynamics at play, and the potential socioeconomic implications of its proposals.

Enoch Godongwana

Image: Independent Newspapers

THE 2025 South African Budget, delivered by Finance Minister Enoch Godongwana on March 12 has emerged as one of the most contentious and closely watched fiscal blueprints in decades. The government expects to collect just over R2 trillion and expects to spend almost R2.4 trillion; the difference is referred to as a Budget deficit, which continues to swell each year.

This deficit is funded by borrowings from world institutions and other countries; an interest repayment accompanies it. We expected the Budget to be presented to the house on February 19. However, at the last second, some political parties and partners of the Government of National Unity (GNU) were not in consensus on the proposed 2% VAT increase, so the national Budget was postponed for the first time in decades in South Africa (possibly the first time ever).

Against a backdrop of sluggish economic growth, rising debt levels, and persistent socio-economic inequality, the Budget seeks to strike a delicate balance between fiscal consolidation and social welfare. However, its delayed release, contentious VAT compromise, and the looming removal of theCovid-19 Social Relief of Distress (SRD) grant have sparked heated debates across political and economic spheres.

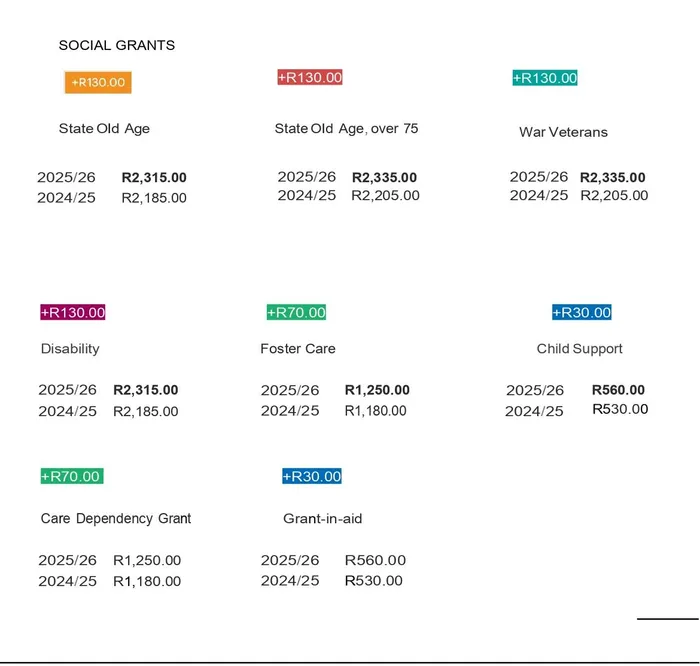

The social grants

Image: Supplied

This humble column will explore some of the key aspects of the 2025 Budget, the reasons for its delay, the political dynamics at play, and the potential socio-economic implications of its proposals.

The economic context: a fragile recovery

According to the National Treasury, South Africa’s economy remains fragile, with growth projections for 2025 hovering at a modest 1.8%. Unemployment stands at a staggering 32.1% (representing an academic economic calculation with real unemployment perched North of 43%), while public debt has ballooned to 77% of GDP, raising concerns about fiscal sustainability.

With lofty hopes and a herculean ambition, the Budget aims to address these challenges by stabilising public finances, stimulating growth and addressing urgent social needs. However, the path to achieving these goals is fraught with complexities, as evidenced by the Budget’s delayed release and the contentious compromises it embodies.

The delay: political negotiations and fiscal constraints

The 2025 Budget was initially scheduled for release in February, but was postponed to March due to protracted negotiations within the GNU. The GNU, a coalition of the African National Congress (ANC), Democratic Alliance (DA) and other parties, has evidenced divergent priorities and shaky ground.

The ANC has emphasised the need for increased social spending, particularly in light of the impending removal of the SRD grant, while the DA has pushed for stricter fiscal discipline and debt reduction. The delay also reflects the Treasury’s struggle to finalise revenue projections amidst economic uncertainty. With tax revenues under pressure and expenditure demands rising, the Budget’s formulation required careful calibration to avoid exacerbating the fiscal deficit, which is projected to reach 4.5% of GDP in 2025.

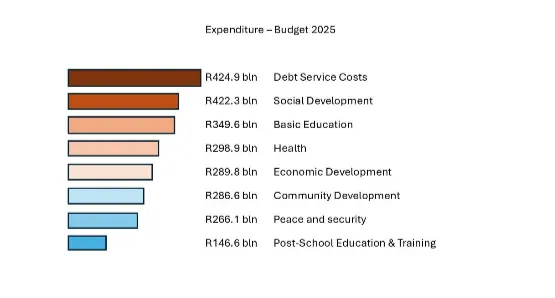

Expenditure

Image: Supplied

The postponement underscores the challenges of coalition governance and the difficulty of reconciling competing interests in a constrained fiscal environment.

The VAT compromise: a controversial trade-off

One of the most contentious aspects of the 2025 Budget is the proposed VAT increase. Initially, the Treasury considered raising VAT from 15% to 17% to generate additional revenue. However, after intense negotiations and public backlash, a compromise was reached to increase VAT by 0.5%, bringing the rate to 15.5%.

While the increase is expected to generate an additional R16 billion in revenue, it has drawn criticism for its regressive impact on low-income households. Notably, during his speech, the minister widened the range of VAT zero-rated goods to lighten the burden.

VAT disproportionately affects people with low incomes, as they spend a larger share of their income on basic goods and services. Critics argue that the increase will exacerbate inequality and undermine efforts to alleviate poverty.

According to some economists, inflation is likely to increase by 0.5% if the VAT increase is 1%. ministerial advisors and proponents, however, contend that the VAT hike is necessary to stabilise public finances and avoid deeper cuts to social programs.

The compromise reflects the GNU’s attempt to balance revenue generation with social equity, but it remains a contentious issue that could strain the coalition’s unity.

Political dynamics: a fractured GNU

The 2025 Budget has unearthed fissures within the GNU, highlighting the challenges of coalition governance. The ANC, under pressure to address social inequality, has advocated for increased spending on grants and public services.

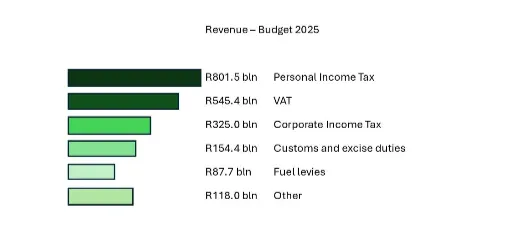

Revenue

Image: Supplied

In contrast, the DA has emphasised fiscal prudence, calling for reductions in wasteful expenditure and a focus on debt reduction. The Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), though not part of the GNU, have been vocal in their opposition to the Budget, particularly the VAT increase and the removal of the SRD grant. The EFF has threatened mass protests, arguing that the Budget prioritises austerity over the needs of people with low incomes.

The uMkhonto we Sizwe (MK) were quick to point out that a VAT increase would hurt black people the most. National Parliament has the duty of debating and then passing the Budget.

In previous years, where one party was in the majority, it was a fait accompli that the Budget would be passed; now, the likelihood of the Budget’s ratification in its current form remains uncertain. While the ANC and DA have signalled a willingness to compromise, the EFF’s opposition and the potential for public unrest could complicate its passage. The GNU’s ability to navigate these challenges will be a critical test of its cohesion and effectiveness.

The removal of the SRD grant: a socio-economic time bomb

The decision to phase out the Covid-19 SRD grant has been one of the most controversial elements of the 2025 Budget. SRD was introduced in 2020 to relieve vulnerable households during the pandemic temporarily; the grant has become a lifeline for millions of South Africans (given that 8 million remain unemployed).

The SRD grant reached 10.9 million beneficiaries at its peak, providing critical support in a country where 55.5% of our friends and neighbours live below the upper poverty line. The Treasury needed a compromise, given the resistance to the 2% VAT increase. They have argued that the grant is unsustainable, costing R35 billion annually and that its removal is necessary to free up resources for other priorities.

However, critics warn that ending the grant could plunge millions into deeper poverty and exacerbate social instability. The Budget proposes replacing the SRD grant with a targeted basic income grant, but details remain vague, raising concerns about its implementation and effectiveness. Entrenched poverty and hardship will be the bleak outcome of the delay in a proposed basic income grant.

The removal of the SRD grant underscores the difficult trade-offs inherent in the 2025 Budget. While fiscal consolidation is essential, the human cost of austerity measures cannot be ignored. The government’s ability to mitigate the impact of the grant’s removal will be a key determinant of the Budget’s success.

The impact of the VAT increase: a double-edged sword

The VAT increase, though modest, is expected to have far-reaching implications. On the one hand, it will provide much-needed revenue to fund critical services and reduce the Budget deficit. On the other hand, it will increase the cost of living for already struggling households, particularly in the context of rising inflation, which stood at 5.3% in early 2025.

The increase is also likely to dampen consumer spending, which accounts for 60% of South Africa’s GDP. With high household debt levels, the VAT hike could further constrain disposable income, slowing economic recovery. The Treasury has sought to mitigate these effects by expanding the list of zero-rated items.

Still, critics argue that these measures are insufficient to offset the broader impact of the increase. The minister was attempting to find a R60 billion shortfall, which was levelled with the 2% VAT in the proposed February Budget; the March Budget also targets a R60 billion shortfall if we count the R35 billion SRD grant removal and the R30 billion of revenue with the half per cent VAT increase now and the further half per cent VAT increase in a year’s time.

Conclusion: a Budget at a crossroads

The poor will not welcome this proposed Budget; the removal of the SRD in 12 months’ time and the gradual increase in VAT by 0.5% now and a further 0.5% in a year’s time will sadly make the poor poorer.

The 2025 South African Budget represents a critical juncture in the country’s economic and political trajectory. Its delayed release, contentious VAT compromise, and the removal of the SRD grant reflect the profound challenges facing South Africa as it seeks to balance fiscal sustainability with social equity.

The Budget’s success will depend on the GNU’s ability to navigate these challenges and build consensus around its proposals. While the VAT increase and the removal of the SRD grant are necessary steps toward fiscal consolidation, they carry significant risks that must be carefully managed.

Ultimately, the 2025 Budget is not just a fiscal blueprint but a reflection of South Africa’s broader struggle to reconcile competing priorities in a time of profound uncertainty. As the debate over its ratification unfolds, the stakes could not be higher. The choices made today will shape the country’s economic and social landscape for years to come.

Advocate Lavan Gopaul is the director of Merchant Afrika.

** The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of IOL or Independent Media.

Lavan Gopaul

Image: Supplied

Advocate Lavan Gopaul is the Director of Merchant Afrika

** The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of IOL or Independent Media.

Related Topics: