Langadha stories of indenture and the days of our lives

Women, generally suffered greater hardships than men. They shouldered the dual burden of plantation work, the double standards of morality, and carried the blame for many of the ills of indenture. Their private cry was, in a sense, a protest against the veil of dishonour that Indian women wore, or rather made to wear during their indenture on the plantations.” - Brij V Lal

Indian medicine man in Colonial India 1896

Image: 1860 Heritage Centre

Women, generally suffered greater hardships than men. They shouldered the dual burden of plantation work, the double standards of morality, and carried the blame for many of the ills of indenture. Their private cry was, in a sense, a protest against the veil of dishonour that Indian women wore, or rather made to wear during their indenture on the plantations.” - Brij V Lal

THE holidays almost always bring together extended family at the communal dining room table. It is most often the case, especially in contemporary times, when family that have not met in a long time use this opportunity to catch up on their "days of their lives".

Lots of the conversation is punctuated with titillating langadha (gossip) stories, either revealing juicy anecdotes of life in the present, or by reminiscing on the past. In most instances, secrets of the past are often revealed in hushed tones to ensure that family dignity remains intact. This Easter, as the conversation rolled on at our dinner table, my ears pricked when one of the aunties spoke of my wife’s indentured great-grandfather having gone back to India.

Eager to learn more, I ensured the drinks flowed merrily, making sure the conversation kept pace with my already racing and inquisitive mind. Beyond the Pietermaritzburg National Archive repository files of Indian indentured history, there lie many stories locked in individual family history that speak to the new direction of writing the experiences of the 152 184 indentured workers, who arrived in South Africa from 1860 to 1911.

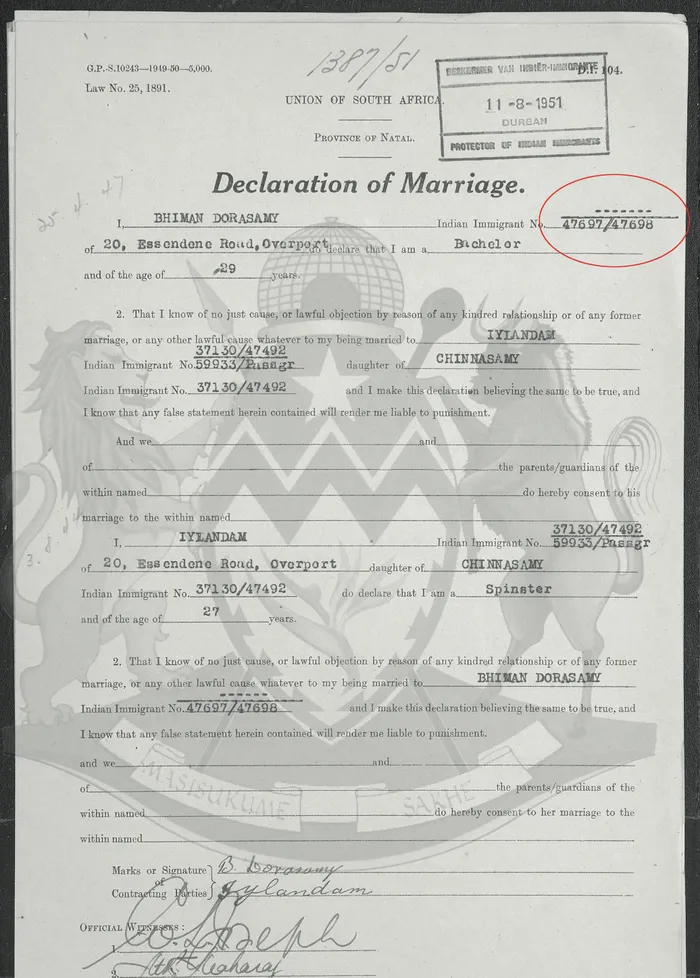

Marriage Certificate of Bhiman Dorasamy

Image: Family Search, PMB Archives

The tales of kidnapping are richly illustrated in the archives with countless tales of how Indian indentured workers were preyed upon by recruiting agents (Arkatiyas) in Indian villages, only to find themselves in imperial colonies stretched across the colonial world. Little information, however, exists on how lives had changed by kidnapping by suitors on the plantations, largely owing to the imbalanced gender ratio of 30 females to every 100 men being recruited to work on indentured plantations.

At the dining room table, the conversation revealed that my wife’s great-grandfather had gone back to India, never to return, after attempts to find his wife proved fruitless. The story from one of my wife’s aunts was that their strikingly beautiful great-grandmother, whose parents came from Chingleput in 1891, was kidnapped by a medicine man at the Bluff as she was visiting relatives.

On her visit when she was kidnapped, she had left both her children, Bhiman Dorasamy (my wife’s grandfather) and his sister, with their great-grandfather’s sister. After spending two months away from her children in the Bluff, and long after her husband left for India, my wife’s great-grandmother eventually came back for her two children, who then became part of her new family under the patriarchy of the medicine man, Tongaat Thatha (grandfather).

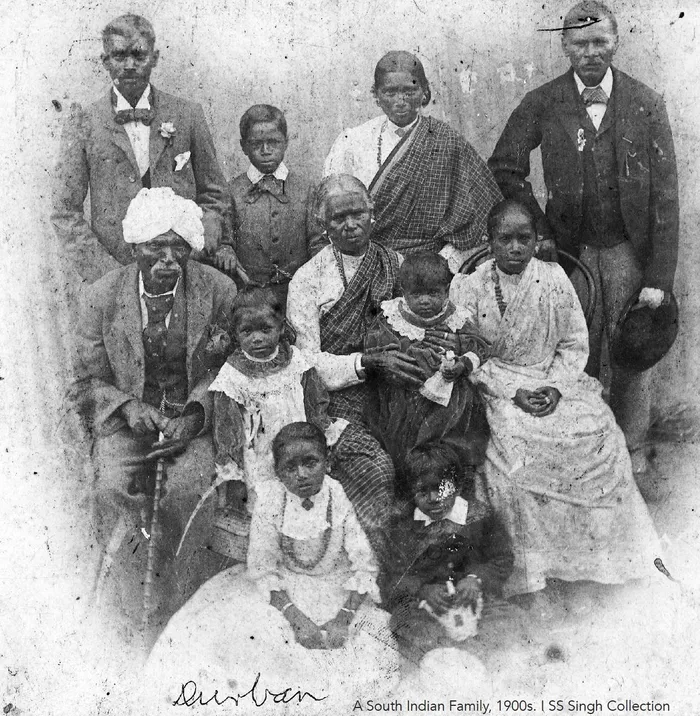

A South Indian Family, 1900s

Image: 1860 Heritage Centre

Tongaat Thatha, had children with his new "bride" when the family had moved to Tongaat, where they lived at the Maidstone Barracks, while he worked at the Maidstone Mill in Tongaat.

Curious to verify the langadha story, my mind raced to the official archive to trace the marriage certificate of my wife’s grandparents. The best way to trace your indentured ancestral roots is to look at the marriage certificate that reveals both the maternal and paternal ancestry through indentured numbers. To my astonishment, Bhiman Dorasamy’s (my wife’s grandfather) father was listed as unknown, and his mother was listed as the child of an indentured couple from Chingleput numbers: 47697, a 29-year-old Muthen Murugan, and 47698, a 17-year-old female Alamalu Vanathan.

Bhiman Dorasamy’s unknown father’s origins confirmed that his father had gone back to India as part of the free passage to India that took place when indentured workers had completed their indentured contract in Natal. There are still many gaps that exist in this particular story, questions like what is the name of Bhiman Dorasamy’s father, and when he was indentured to South Africa, that I hope to complete in revealing the full story.

What is clear is that there lies a fascinating history of indenture that lies, right under our very noses, waiting to be unravelled, until it is unlocked in our individual family stories.

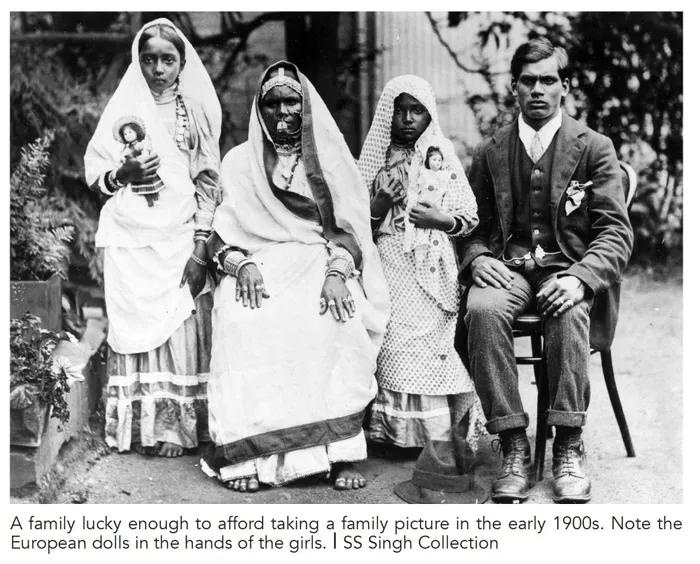

A family lucky enough to afford taking a family picture in the early 1900s

Image: SS Singh Collection

According to a seminal paper, Women under Indentured Labour in Colonial Natal, 1860-1911 by Jo Beall, published in 2012, once Indians were free from their indentured contracts and the conditions of estate life, marriage and the creation of a stable family became a priority. The practice of child marriage was given a particularly unsavoury situation created through the sexual imbalance amongst Indians in the colony.

“There is evidence that young brides could be purchased from their parents and that some unscrupulous guardians would marry a daughter, married by religious rites to one man, and married her to another for an additional fee. In many cases, the girls are 13 years old, the legal age of marriage. Nundy (1902) reported that in Verulam alone, in only two out of ten marriages solemnised in one month were the girls even approaching the legal age; the rest were between 10 and 12 years old.”

Further reports of unusual marriage practices of indentured workers are revealed the Report of the Protector of Immigrants for the year 1886, which revealed that he, the protector:

“still thinks the unnatural system of betrothal (which becomes almost a sale) of young girls is a cause of mischief, and I hope legislation designed to minimise the evils will be initiated, although it is difficult to see in what way any enactment can best strike at the system which is in the eyes of Indians hallowed by the custom of ages.

"Many young men, after spending a considerable portion of their earnings in supporting a family for months, in consideration of one of the daughters being betrothed to them, find themselves supplanted in favour of the parents, if not in that the daughter, by some new suitor who brings further valuable consideration to the family coffers. The passions thus aroused often find their outlet in murderous assaults and sanguinary affrays.”

An indentured family walking on the Durban Esplanade, 1900s

Image: 1860 Heritage Centre

The history of family life in Indian indenture is interesting. Indenture, like slavery and migrant labour, disrupted family and kinship bonds to advance colonial accumulation.

For the indentured Indian, the hopes of a normal, structured family life like they had in their original homeland were but a mirage. The yearning may account for the abnormally high rate of kidnapping, suicide, and murder on the plantations and within the system of indenture that saw low numbers of women recruited, making family living virtually impossible.

On the 384 ships that transported indentured workers, 62 % were men, 25 % were women, with children constituting 13 % of the total of 152,184 souls that arrived on South African shores between 1860 to 1911.

Selvan Naidoo

Image: Supplied

Selvan Naidoo is the Director of the 1860 Heritage Centre

Related Topics: