The railroad of death: Angola and the ticket stamped no return

In this column, Ashwin Desai and Goolam Vahed bring to life a story of working class Indians from Natal, who left to Lobito Bay for a better life. Their story has largely been forgotten. But it is bloody reminder of the price people paid to find a home in Africa.

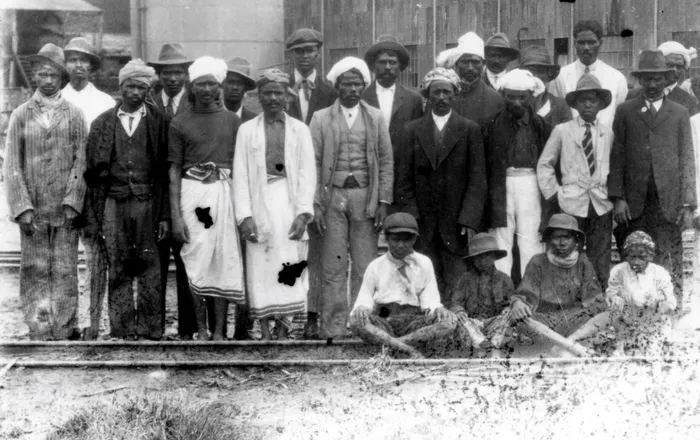

Indian railway workers were utilised in Natal, Uganda and Angola

Image: Supplied

It is that time of the year where stories of freedom echo through South Africa. It is a remarkable narrative of a prisoner Nelson Mandela becoming president of a democratic South Africa. But often we get lost in the grand fairy-tales of struggle and liberation. In this column, we bring to life a story of working class Indians from Natal, who left to Lobito Bay for a better life. Their story has largely been forgotten. But it is bloody reminder of the price people paid to find a home in Africa.

‘Abandon all hope, you who enter here’ - Dante’s Inferno

THE early 1900s saw an intensification of white antipathy towards Indians. Durban had witnessed Gandhi being hounded by white racists when he arrived back from India. Anti-Indian legislation multiplied. The main white newspapers railed against the Indian presence, raising a multitude of issues. For whites Natal had become "a mere dumping ground for the refuse population of India".

One of the ironies is that one of the charges against Indians was that they were dominating trade and outcompeting whites. If their competitors were "mere refuse" then what did that imply about their own capacities? For the white colonists Indians were here to do their bidding. As Gandhi’s supporter Henry Polak put it, "the Indian labourer is often regarded by his employer as of less account that a good beast, for the latter costs money to replace, whereas the former is a cheap commodity".

The white colonists also heaped a £3 tax on the indentured to force them to re-indenture or go back to India. It was a way to prevent them from making a life in the city, freed from the shackles of indenture. So callous was the local white colonist that even the arch-imperialist Winston Churchill remarked that Natal was “the hooligan of the British Empire”.

It was in this context that the indentured sought to find ways to escape this mounting threat to their lives and livelihood. In this context a group left Durban, their destination, Angola. The British were building the Benguela Railway, so that Lobito Bay could be available for minerals mined in Katanga in the Congo.

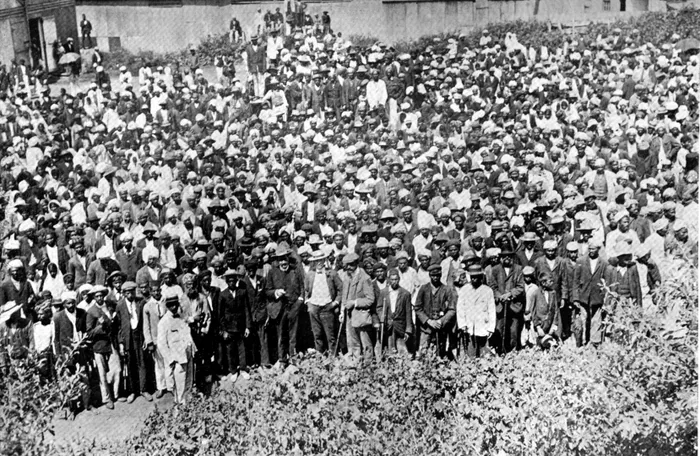

Mass meeting of Indian workers preparing to leave for Lobito Bay

Image: Supplied

Starting in 1903, the 1 343 kilometres line took a quarter of a century to complete.

Finance and labour were serious problems. Disease and the slave trade had depleted the local African population. Norton Griffiths and Company, contracted to build the railway, turned to Natal’s working-class Indians. Indians were seen as a good labour source because many had worked on the railways and gained a favourable reputation.

Griffiths approached John Stone, a contractor involved in the construction of the railways in Natal, to negotiate with the Natal government for 2 000 workers. With conditions on the plantations harsh, debts mounting and the future without hope, Indian workers signed up. By the end of February 1907, 1 200 Indians signed up on two year contracts at £2 per month, and food, accommodation and medical care. Recruits, however, had to pay £2 for transport to Lobito Bay and settle their tax debt to the Natal government.

The Indian government agreed to the scheme on March 25, 1907, as the Natal authorities insisted that the alternative was unemployment and repatriation. While waiting to depart, the workers were housed in Brickhill Road for six weeks in what the Indian Opinion described as "overcrowded, dilapidated, and filthy conditions".

The men departed on the Berwick Castle on April 12, 1907.

In all, 2 274 Indians went to Lobito Bay: 1 212 men, 423 women and 639 children.

Mass meeting of Indian workers preparing to leave for Lobito Bay

Image: Supplied

Of these, 823 had arrived in Natal under Law 25 of 1891, which permitted them to return to the colony after completing their contract; the remainder were subject to the immigration law of 1895. By leaving Natal, they forfeited their right to return and their free passage to India.

Workers had been told by Stone that they would work 200 kilometres inland from Lobito Bay, where the weather was "similar to Madras" from whence the majority originated. They were in for a shock. The climate was terribly dry and the terrain hazardous. The country was mountainous and almost waterless as the annual rainfall was a mere 250 millimetres per annum. A headline in a Natal Advertiser report on July 5, 1907, summed up the plight of Indians: “A dismal tale.”

The stories of some the workers are harrowing.

P Moonsamy, a free Indian, had travelled to Lobito Bay to open a store, returned to Natal in early July and told the Protector that conditions were terrible. The workers were used mainly to do the onerous work of clearing the land. They were given a little tin of "oily, sticky water" for a whole day.

For the two months he had been there, Moonsamy reported that many workers were not able to bath and were "covered in dirt and infested with flies". Some died and others deserted to Damaraland in present-day Namibia. There were no medical facilities and correspondence to family in Natal was intercepted and destroyed. Only 700 Indians remained in Lobito Bay when Moonsamy left. Moonsamy’s allegations were supported by a report from the British consul at Luanda, HA Mackie, who confirmed in July 1907 that large numbers of Indians were deserting, most in an “emaciated condition”.

The Natal government refused to get involved but when reports continued to filter through to Natal, Governor Nathan asked Mackie to prepare an official report. He reported in January 1908 that desertions were continuing, suicides had been reported, and malaria, sleeping sickness and jigger flea were rife. In March 1908, 540 Indians departed from Lobito Bay on the Newark Castle. They reached Durban on April 6. It was a ship of disease and death.

There were 80 cases of malaria, 20 of dysentery, 150 of jigger flea and several instances of enteric fever and beriberi, a disease of the nervous system that resulted in partial paralysis of the limbs. Four died during the voyage and five had their legs amputated because of gangrene.

Another 615 Indians returned on the Alnwick Castle in May 1908. When the ship reached Durban, there were 50 cases of malaria and 400 cases of jigger flea, while others suffered from phthisis, dysentery and acute lung diseases like bronchitis and pneumonia. Dr Fernandez described "the general condition of practically the whole of the Indians constituting this shipment as one of extreme debility". Four amputations of legs were performed at Addington, nine returnees died, and forty were hospitalised.

An estimated 600 Indians died in Angola. It was a massacre.

Indian Opinion described the returnees as most "repulsive looking". Their clothes were “appalling” even in “comparison to indentured Indians”. The “dirt rags were barely sufficient to hide their nakedness, while their long tangled hair presented a picture of barbarism”.

The Angolan venture had turned into a killing field. But this was only the beginning of the nightmare.

The Natal government insisted that by leaving the colony, they lost the right to remain in Natal. Of the 1 606 Indians who returned, 658 were allowed to remain but the remainder had to go to India. The Natal Indian Congress took up the issue with the government as many did not want to return to India, while others were in no condition to walk, let alone get on a ship.

But the Natal government were unrelenting. They point blank refused to talk to the Congress. After visiting Lobito returnees at the Bluff in Durban, NIC president Dawood Mahomed told Indian Opinion that the men complained bitterly that although many were of 10 years standing in the colony, they were being sent to India against their will. They "knew Natal more than India".

The Congress communicated its concerns to the government on April 27, 1908: “Committee met Indians returned from Lobito Bay. They did not want to go to India and claimed domicile rights. Request information as to why men who were in the colony in the first instance have been sent to India. Respectfully enquire whether any arrangement has been made regarding looking after these men in India.”

This enquiry was simply ignored. This was the behaviour of Churchill’s “wretched colony”.

Protector Polkinghorne simply wrote to the Colonial Secretary on April 27, 1908, in legalese; “although some of the Indians would, no doubt, have remained in the colony if they had been allowed to do so… (t)he contract entered into before going to Lobito Bay expressly stated that they were not allowed to return to Natal again".

Repatriation went ahead. By June 1908, virtually all the returnees were sent to India. Three women were "saved" from deportation. Their husbands died at Lobito and colonial-born children, and friends in Natal and none in India, they refused to go back. As local Indians raised their voices in protest, Protector Polkinghorne petitioned the government. In a rare instance of mercy they were allowed to stay. But their meanness could not be offset as they insisted outstanding tax debts had to be met.

Research allows us to write their lives into ours.

One of the three women was Adiamma Venketramadu. She had come to Natal on February 6, 1898, from Chingleput with her husband Nagadu Ramadu. Ramadu’s death left her with three children aged 16, 15 and 12. Adiamma lived for almost half a century until her death in Overport in 1953.

Ragi Nagadu was a "Lobito widow" at 32 as her husband, Veersamy Ramdu died there. If Ragi had left her village in search of a better life, her story was especially tragic. She lost her eight-year-old daughter, Ankammah, in 1901. Her son Nagadu, aged 14, died in Lobito Bay, leaving her alone. Her brother-in-law Parasamder, who was working in Natal, promised to take care of her. Ragi disappears from the records at this point.

Muniamma Annappa was also allowed to remain as her children Arkadu, Muniamma, Muni and Gungadu, were colonial born. She and her husband Chengadu had arrived on February 6, 1898, from Chingelput. After serving their indentures in Mount Edgecombe, they struggled under the weight of tax – they would have had to pay £15 per annum – and saw the Lobito option as a stroke of good fortune. Chengadu died in February 1908. Muniamma continued to live in Natal until her death in 1940 at the age of 70. She was a hawker of fruits and vegetables, and at the time of her death was living in Sydenham.

The details of the lives of the three women, albeit routine on the one hand, are revealing because they give us a window into the trajectory of the generations that came after indenture. But it is more than that. It shows the depth of this idea of Natal as "home", irrespective of the harsh conditions. Muniamma, for example, could very well have succumbed to the pressures and left for India. But she chose to make Natal home, and by the time of her death in 1940 had 19 grandchildren and a legacy that continues to the present.

How do we think of the past in the present? The long struggle to belong? It is not just a tale of redemption but also one of caution. The other side of belonging is often othering. We saw that through the nineteenth and most of the twentieth century as headlines warned of the “Asiatic Menace” and government commissions demanded repatriation.

We see it today in South Africa with the rise of ethno-nationalist demagogues who seek, like the racist regimes of the past, to define belonging in narrow and narrower terms. In this time when racial divisions once more fill the airwaves, where the right to belong is questioned, maybe we should ponder the words of the very first President of a democratic South Africa: "each of us is intimately attached to the soil of this beautiful country as are the jacaranda trees of Pretoria and mimosa trees of the bushveld". We would add to Mandela’s list the cane fields of the south and north coast of KZN. It was here, that the desire to belong was grounded more deeply than any colonial plantation.

While this is a tale of death we should always remember as Joan Didion put it "we tell ourselves stories in order to live".

Ashwin Desai

Image: Supplied

Goolam Vahed

Image: Supplied

Ashwin Desai is at the University of Johannesburg and Goolam Vahed at the University of KwaZulu-Natal.

** The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of IOL or Independent Media.

Related Topics: