Waves of Indian migration

From gold miners to indentured labourers

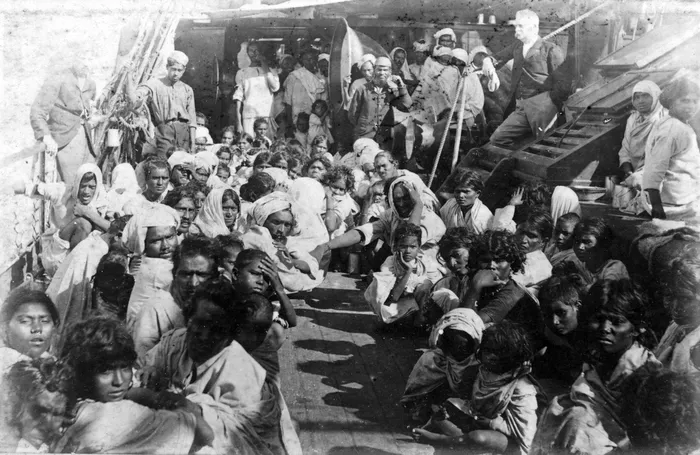

Indentured Indians on board the SS Umona heading for Natal in 1903.

Image: 1860 Heritage Centre

INDIANS had come to South Africa through various routes. One theory posited by Professor Cyril Hromnik pointed to Dravidian gold miners having settled in Southern Africa. Their likely port of entry was present-day Maputo, traversing Komatipoort, a name derived from Tamil, and travelling beyond into the Karoo.

The next understudied route of migration was that of Indian slaves trafficked by slave-trading Europeans to make up 50% of the slave population of the Cape since the mid-17th century.

The best-known wave of migration was that of Indian indentured workers, who came to grow the colonial economy of Natal. Alongside these 152 184 workers that came from 1860 to 1911, Passenger Indians, who paid for their passage, came to South Africa as traders, artisans, and workers, primarily originating from the Gujarati region of India, specifically the west coast.

The next wave of migration saw Sikh and Pathan soldiers, who had come at the turn of the 19th century to fight in the Anglo-Boer, Zulu, and Basotho wars. The last wave of Indian migration to South Africa was those who arrived in post democracy.

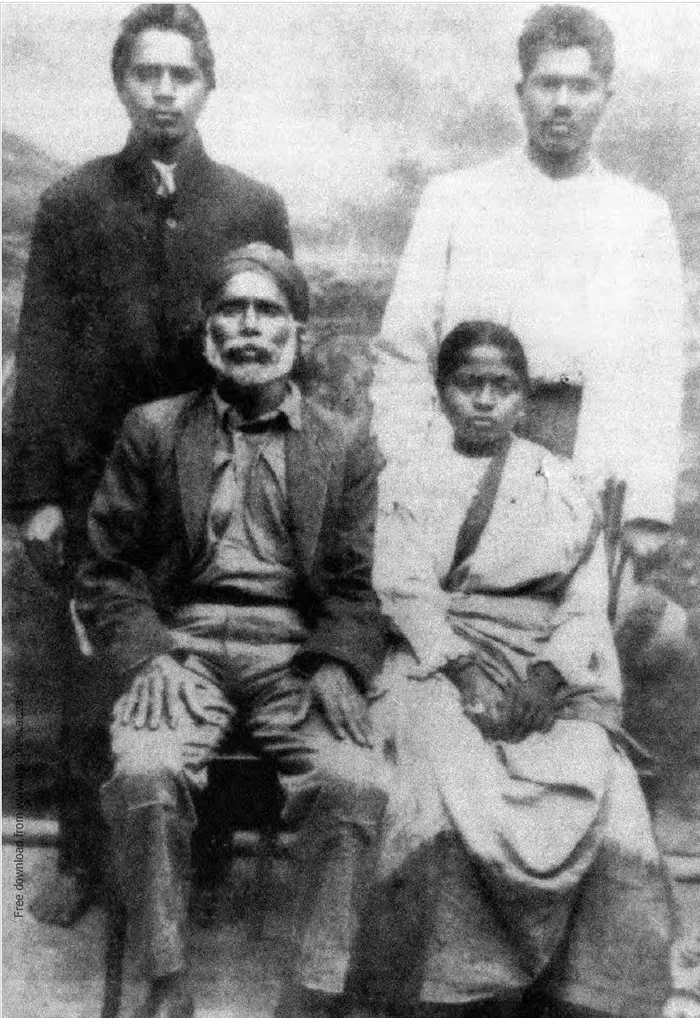

Munigadu Rangadoo and his family walked from Dar-es-Salaam through Mozambique after they were repatriated. They were arrested as Prohibited Immigrants and deported back to India.

Image: 1860 Heritage Centre

Throughout these waves of migration, anti-Indian legislation was introduced to curb economic growth and deny residential status for Indians living throughout South Africa. Law 3 of 1885 provided for separate residential and trading areas for Indians and “Arabs” in the Transvaal. The Orange Free State (Free State) prohibited Indian settlement from 1891, and the Cape introduced immigration restrictions from 1903.

Restrictions to prohibit Indian immigration intensified in the last decade of the 19th century with the Immigration Restriction Act (Natal) in 1897 and its subsequent amendments in 1900, 1903, and 1906. The act imposed educational, health, age, and means test restrictions against Indians other than indentured workers who sought admission to the country, or entry to the Transvaal and Cape. This act virtually stopped all further immigration of free Indians into the colony.

By 1913, the Immigrants Regulation Act (No 22 of 1913) ensured that persons not literate in a European language and undesirables, ie. on economic grounds or account of standards or habits of life, could be excluded from the country. The then Minister of Interior classified all Asiatic persons as undesirable. Indian immigration stopped.

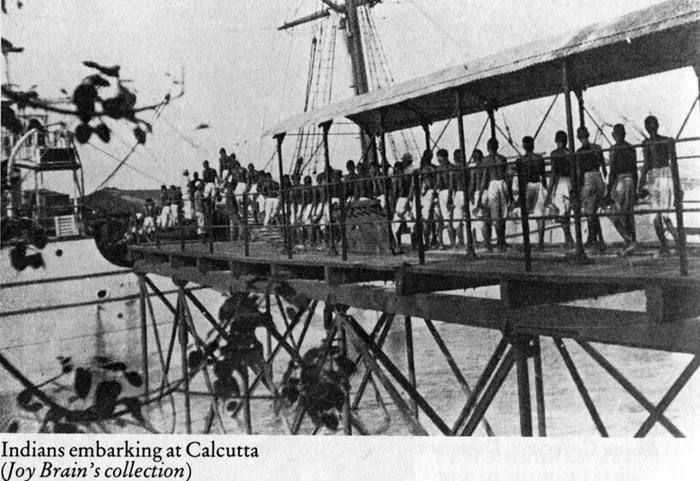

Indentured Indians embarking from the Port City of Calcutta in India.

Image: Joy Brain Collection at the 1860 Heritage Centre

According to eminent scholar on indenture, Brij Vilash Lal, there were 149 791 Indians in South Africa in 1911. Of these, around 30 000, or 20%, were of passenger origin, while just over 130 000 lived in Natal. Following the gold rush from 1886 to 1910, immigration laws were used to prohibit 34 872 Indians from entering Natal, while Indian traders were barred from prime trading areas. The final batch of indentured Indians arrived on the Umlazi on July 21, 1911.

Drawing on official statistics kept by the Natal government to monitor indentured labour, Maureen Swan, the author of Gandhi, The South African Experience, estimated that 48% of the total of 152 184 indentured labourers, who arrived in Natal returned to India.

In an academic paper titled South Africa to India: Narratives of a Century of Repatriation (1871-1975) by Professor Uma Dhupelia Mesthrie, she noted that “The Umvolosi, Umzumbi, Umsinga, Umona, Inchanga, Incomati, Isipingo (African-named ships inspired by rivers and place names in Natal) were ships chartered by the South African government in the 1920s and 1930s to transport Indians to India who were leaving on a repatriation scheme offering free passages and cash bonuses.

"These ships have not gained iconic status in the public imagination of Indian South Africans as have the Truro and the Belvedere, which brought the first loads of indentured Indians from Madras and Calcutta. Respectively, to the colony of Natal in November 1860.

Governed by "methodological nationalism", the reverse flow of Indians from South Africa to India has equally not excited the interest of South African historians.”

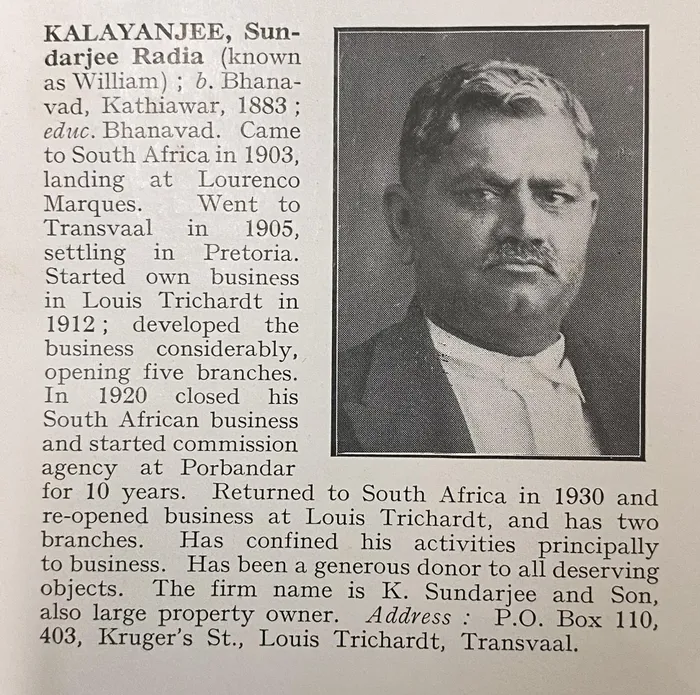

Kalayanjee Sundarjee Radia, a trader passenger, who landed at Lourenco Marques.

Image: The South African Indian Who's Who/The Dhanee Bramdaw Family.

In 1920, Indian immigration to South Africa was still a complex issue with restrictions firmly in place. The focus, centred on more restrictive policies concerning Indian trade, residence, and immigration. The post-war period saw anti-Indian sentiment rise, leading to proposed legislation aimed at curbing Indian influence that saw the government implement measures to limit their rights and control their movements.

Out of desperation, many Indians sought to enter the country illegally. Andrew Macdonald of the University of the Witwatersrand first researched the topic of prohibited and illegal Indian immigrants in a seminal paper done in 2014 titled, Forging the Frontiers: Travellers and Documents on the South African - Mozambique Border, 1890 -1940.

The archive is littered with cases relating to prohibited Indians.

Professors Aswin Desai and Goolam Vahed seminal work, Inside Indian Indenture, highlights the sad tale of prohibited immigrant Munigadu (57684), a former indentured Indian, who, together with his family walked 3220km from Dar-es-Salaam (Tanzania) to Lourenco marques (present day Mozambique) to Northern Natal where they were arrested at Mkuzi and deported to India.

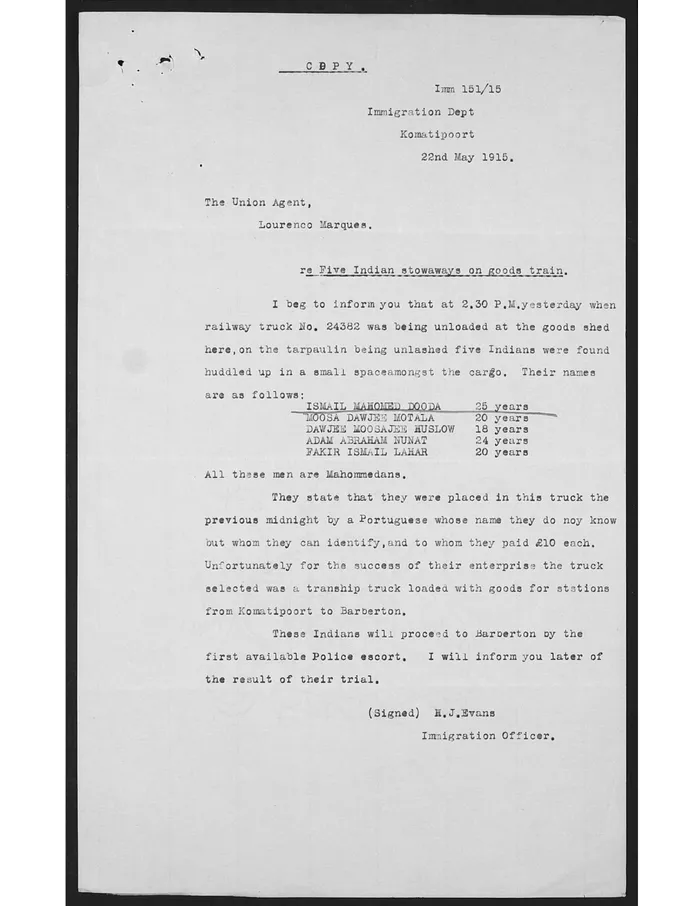

Archival transcript of five Indian stowaways on a good train.

Image: Indian Immigration Files at the Pietermaritzburg Archive Repository

The proximity of Lourenco Marques, Transvaal (now Gauteng), and Komatipoort, which sits at the border of South Africa and Mozambique, triangulates hordes of files located at the archives that speak to prohibited Indians arriving in the country through this route.

These locations show a good settlement of Indians, evidenced in an article in the Indian Opinion 15th June 1907, that speak to Indian stores located at Delagoa Bay and that a train trip from Komatipoort to Barberton reveals that many Indians worked on farms located there with a “good many Madrassis among them” at Komatipoort and Barberton.

An archival report at the Pietermaritzburg archives repository titled the Clandestine Immigration of Indians from the office of the Immigration Department at Komatipoort, dated November 20, 1914, show that Mahomed Jusab, a registered hawker, was successful in smuggling three Indians from Delagoa Bay to Nelspruit and from there to Newclare (Johannesburg) where they were to be employed as laundry men.

Kesave Daganum, Laloo Bhuryad, and Ramjee Kursam were discovered at Newclare and were accompanied by Chiba Dya, who was ordered by the magistrate at Baberton to be deported.

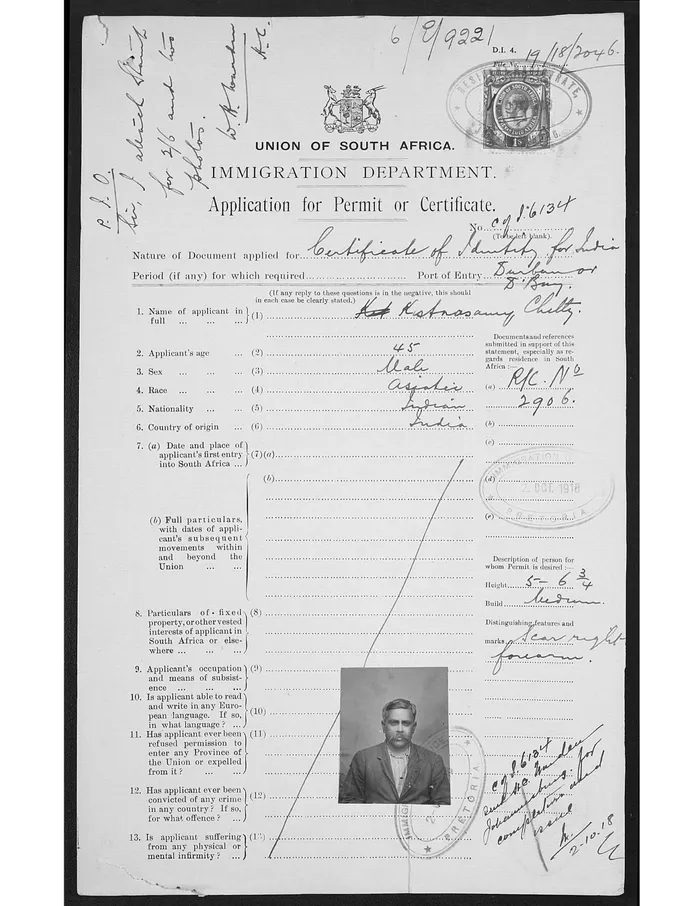

Application permit for Kistnasamy Chitty to leave South Africa and visit his wife in India, who had given birth to their fourth child.

Image: Indian Immigration Files at the Pietermaritzburg Archive Repository

A year later, on May 22, 1915, another archival document reported to the Union Agent at Lourenco Marques, informed by the immigration officer, JJ Evans at Komatipoort, that when the railway truck was being unloaded at the goods shed, five Indians were found huddled up in a small space among the cargo.

Ismail Mahomed Dooda, 25, Moosa Dawjee Motala, 20, Dawjee Moosajee Huslow, 18, Adam Abraham Nunay, 24, and Fakir Ismail Lahar, 20, were placed on the train the previous midnight by a Portuguese whose name they do not know but whom they can identify, and to whom they paid 10 pounds each. All five of them were arrested and were to proceed to Barberton for their trial.

Further evidence of the trouble with prohibited Indian immigrants drew the attention of the Rand Daily Mail with an article that reported on a case that occupied the Johannesburg law courts for 12 days. The judgment was of great interest to the Indian community that ruled against the appeal of Mohamed Moosa, a 34-year-old storekeeper, and Mahomed Pasha, a 50-year-old bookkeeper, who were charged with aiding and abetting prohibited immigrants to enter Transvaal.

The evidence showed that “there had been consultation between the accused and the prohibited immigrants in Delagoa Bay, preparatory to their crossing the border. Further, it had been shown that, after the men had been successfully smuggled into the province, they were taken to Johannesburg and even accommodated there".

The judgment reported that the accused would serve six months imprisonment with hard labour.

Uma Dhupelia Mesthrie’s keynote address presented to the 2006 Colloquium at the University of the Witwatersrand, titled The Place of India in South African History: Academic Scholarship, Past, Present and Future highlights that the “poorest of Indians in South Africa, many of whom were in fact colonial-born, were encouraged by various bonus schemes to return to India permanently with the aid of the Indian government only to find that they had not exchanged the miserable life they led in South Africa for a better one in India".

Many of these indentured immigrants, together with those prohibited Indian immigrants, who make up the 1.7 million Asians of South Africa’s population, make the study of Indian migration into South Africa a far more complex area of study in understanding the lives of those who hoped to make a better life for themselves in their African homes.

Selvan Naidoo

Image: Supplied

Selvan Naidoo is the director of the 1860 Heritage Centre

** The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of IOL or Independent Media.

Related Topics: