The search is on: help uncover the tin tags of our ancestors

Today, they are rare relics of a courageous journey that helped shape South African history

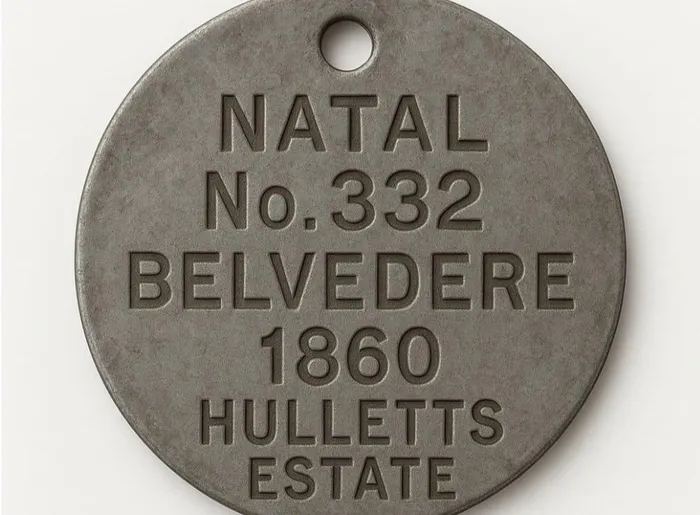

The image of the tin ticket is a historically-inspired digital representation, as no original tin tag has yet been found fully intact and clearly photographed. The number is fictional.

Image: Supplied

IN 1860, the first Indian indentured labourers arrived on the shores of Natal, each carrying a little more than hope, and a simple tin tag stamped with a number and an estate name. These small metal discs, worn around their necks, were their only form of official identification in an unknown land.

Today, they are rare relics of a courageous journey that helped shape South African history. We call upon descendants across the country and the diaspora: search your homes, your family trunks, and your memories. A forgotten tin tag may still survive, a silent witness to endurance, sacrifice, and pride. Finding one is not merely discovering an old object. It is reclaiming a priceless piece of our collective soul.

The original identity tags

These tin tags, or “tin tickets”, were issued up until 1911. A typical tag from the Calcutta Depot might have been stamped "NATAL No. 360, BELVEDERE 1860, HULLETTS ESTATE", bearing the number assigned to the labourer and the estate to which they were sent.

Worn like a badge of survival, the tin tag symbolised both bondage and resilience. Each one tells a silent story, of sweat under the African sun, of ocean-crossed dreams, and of the roots of a community that would one day flourish. Even a single tag, if recovered, holds enormous historical importance. They may be tucked away in old trunks, jewellery boxes, sewing tins, attics, or storeroom, perhaps passed down unknowingly as heirlooms.

If found, preserve it carefully. Consider sharing it with the 1860 Heritage Centre or similar heritage initiatives. Each recovered tag gives voice to our ancestors and helps illuminate a story too long kept in the shadows.

From tin to paper: the long road of identification

The tin tag was just the beginning. After that crude piece of metal came an expanding web of documentation, not for empowerment, but for control. These evolving identity systems were designed to regulate the movement, aspirations, and very existence of Indian South Africans.

Pass laws (from 1888)

In Natal, Indians were compelled to carry passes restricting their movement. These were not opportunities. They were shackles. Without a pass, one had no right to move, to work, or to exist freely.

The Asiatic Registration Act (1906) the “Black Act”

This infamous law in the Transvaal forced all Indians to register, provide fingerprints, and carry certificates. Refusal meant jail or deportation. The act sparked Mahatma Gandhi’s historic Satyagraha movement, non-violent resistance born in the heart of South Africa. Herein was the genesis of the mechanism for the freedom struggle to gain Independence for India led by the Mahatma.

Poll tax certificates

Indians were subjected to poll taxes, a fee for existing in the land they helped to build. Upon payment, a certificate was issued. It was another degrading reminder that their presence had to be constantly justified.

Inter-provincial travel permits

To travel between provinces, even to visit family - Indians had to apply for permits. They were effectively trapped by invisible borders. The Orange Free State outright banned Indians from residing within its territory.

Population Registration Act (1950)

This apartheid law classified citizens by race, white, black, coloured, and Indian. This label determined everything: where one could live, work, learn, even love. For Indians, it was a sentence of second-class citizenship.

Apartheid-era identity documents

Indians had to carry identity books that revealed their racial classification. Police could demand them at any time. Forgetting your ID could mean jail.

1994 and beyond: a document of dignity only

It wasn’t until the fall of apartheid that a new, democratic South Africa introduced a single identity document for all citizens, regardless of race. Finally, a card that represented equality, not division.

Why it matters today

This history still casts a shadow. For many families, stories are fragmented, ancestors unnamed, and links to the past lost. That’s why the tin tag matters. These small discs were not just meant to track labourers. They marked the first steps in a long journey of being documented, regulated, and too often dehumanised. But now, if found in a drawer or a box, they become something else: a symbol of survival, a link to the past, and a treasure of untold worth.

Call to action: serve, preserve and honour

Are you descended from indentured labourers? Do you have an old biscuit tin filled with odds and ends? An heirloom passed down without a story? Look again. You might find a rusty disc, stamped with a number and a name. If you do, handle it with care. Photograph it. Record its details. And most importantly - share its story with your family, your community, or a heritage organisation.

Each recovered tin tag is a voice returned to our history.

By finding and honouring these simple tin tags, we reconnect with the courage, dreams, and dignity that built our future.

Jerald Vedan

Image: Supplied

Jerald Danasekera Vedan is an attorney, conveyancer, notary public and a labour law commissioner. He is also an author and poet and has a passion for history, particularly the journey of South African Indians from 1860 onwards.

** The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of IOL or Independent Media.

Related Topics: