Indenture and the toolbox that made a home

Memories of an indentured ancestor

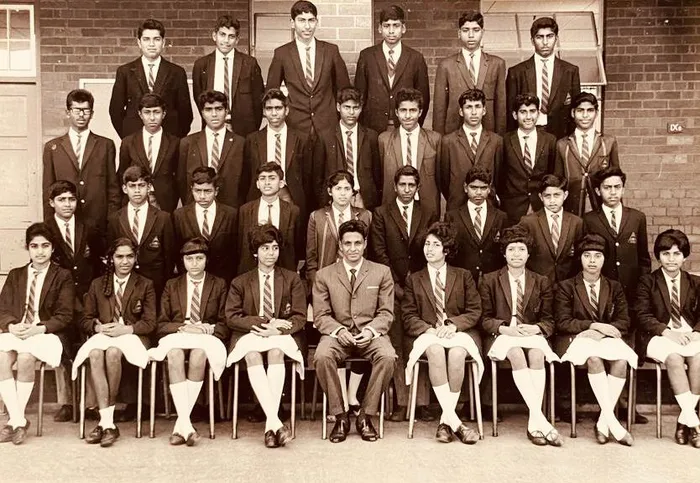

Nithianathan Govender and his supervisor at Game Stores, 1980s.

Image: Govender Family Collection

IN DEATH, my father-in-law’s vibrant family home has metamorphosed into an empty shell that only holds memories for the living. In time, all the cherished contents that took a lifetime to gather were dispersed like dandelions to the wind, floating along a new path in search of memory anew.

My wife’s ancestral childhood home in Phoenix, to the North of Durban, is now ready for another family waiting to create memories in the municipal-built house, my father-in-law called home. As the household contents were scattered from the Highveld Johannesburg plains to the former banana plantations of Hillary in Durban, I was strangely bequeathed my father-in-law’s toolbox.

It is a strong, sturdy metal toolbox, well-resourced and neatly arranged with a set of tools that are unlikely to callous my soft hands and will most likely last until my son inherits it. As I went through the toolbox, trying to make sense of its contents, it dawned on me that the toolbox was a metaphor that locked away all my father-in-law’s hopes, dreams, and aspirations in crafting opportunities that constantly evaded his working-class ancestry.

In the toolbox, there were the finest tools that evidenced my father-in-law's intense tenacity to make his municipal house the finest castle his children could call a home. The toolbox foregrounded his resilient, unstinting dedication towards making things beautiful for his family and to provide what he and his indentured ancestors only dream of having.

Nithianathan Govender with his Matric Class of 1966 at Clairwood High School.

Image: Supplied

In a book titled Bearing Witness: Essays in honour of Brij V Lal, Professor Goolam Vahed pays tribute to one of the world’s finest scholars on indenture, stating that: “History is about people, and the strength of Lal’s work is his ability to put human faces to our pasts, and to present characters with whom his readers can connect. This kind of history gives voice to the perspectives of ordinary men and women who in the past were neglected or suppressed for one reason or other - class, age, gender, race, ethnicity.

"Lal’s project of telling the stories of ordinary and not-so-ordinary people in ways that are accessible to the wider public is important, as we are living in a time when the academy valorises academic journals that are never read by those who feature in these stories.”

Nithianathan Govender was born in 1948 to Murugasen and Lutchmee Govender of Clairwood. Both Murugasen and Lutchmee were colonial-born, with their grandparents hailing from places like Chittoor, Vellore, North Arcot, and Chengalpattu to provide their labour in building the modern world we know today.

Murugasen and his father, before him, were indentured special servants, working as waiters in colonial beachfront hotels dotted along the Durban mile. From their rented communal family home in Clairwood, Lutchmee mastered the art of murukku, vada, and samoosa, adding to the household income.

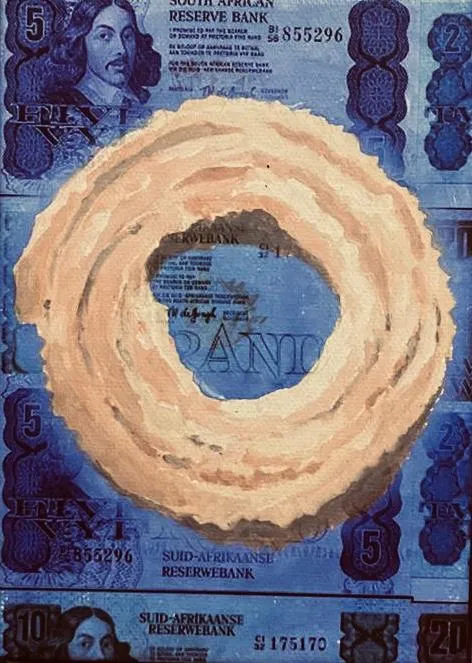

Detail of an artwork titled 'I am an African" housed in the 1860 Heritage Centre’s Art Collection.

Image: Supplied

Nithianathan helped his mother, folding samoosas and making murukku and vada, selling them in Clairwood, peddling their wares on a trusty bicycle while he completed his matric at Clairwood High. An accident with a Coke truck scarred his right calf muscle for life, a scar, he wore with pride, often reminding me of it, years later, whenever he folded samosas with Shylock precision.

At the same time that Nithianathan had completed his matric in 1966, hundred and six years from when the first lot of indentured workers arrived to Natal in 1860, a journal article, the "Culture of Poverty" and the South African poor by Geoffrey H Waters in 1978, estimated that 64% of Indians living in South Africa, lived below the poverty datum line.

In 1968, Nithianathan’s family moved to Road 502 in Chatsworth when the horrid Group Areas Act saw thousands of families move to la]bour reservoirs well away from the city centre. The municipal-built houses at Chatsworth saw the blossoming of a relationship with my mother-in-law from Road 703. The couple married in 1973, seeing them move to a rented property in Merebank, where my wife’s formative years were spent learning Tamil from the hallowed Merebank Tamil School Society.

The desire to own a house eventually came to pass when Nithianathan was allowed the overly priced municipality’s option of rent-to-purchase property in newly built housing schemes at Phoenix during the 1970s to 1980s. In those early years, Nithianathan’s trusty toolbox sprang into being as the young family moved into their Phoenix home. Each weekend, Nithianathan laboriously collected slate tiles and burnt sienna corobrick clay bricks to secure the pathways and boundary walls.

His toolbox housed garden tools that saw him win the most beautiful garden competition in Stanmore, Phoenix, in 1983. Years later, the beautifully manicured Kikuyu grass was manicured with precision that I marvelled at whenever I visited the home. Nithianathan’s matric pass enabled him to qualify for more administrative jobs. He held his first job as a despatch manager at the construction company of Alexander Hamilton.

He then moved to Game Stores, and eventually retired in the same position for the Bears Group based at the Models furniture store, from where he collected numerous awards for his meticulous administration. He worked six days a week, barely taking a single day’s leave from work.

Nithianathan’s Clairwood upbringing would hold him in good stead when he was retrenched from Alexander Hamilton, seeing the family turn to selling vada, murukku, and samoosa to make ends meet. By the time my wife was ready to go to the University of Durban-Westville in the 1990s, my mother-in-law had started work at Twin Clothing, where most of the clothing factory workers resourcefully created a system of lottery to pay for additional costs that families couldn't normally afford to pay in one go.

Nithianathan and my mother-in-law were able to pay for my wife’s university registration fees through the generosity of factory workers in making sure that they collected her lump sum lottery dividend in February that year.

Seven years since Nithanathan had passed away in 2018, a mere two years from when he retired, a university professor from the same university who taught my wife, Sezela born Professor Kiren Thathiah, congratulated her on her recent promotion as a Deputy Principal at Amanzimtoti High School in a Facebook comment that read: “Hearty congratulations. This is so poetic. For years, I used to travel past the school and look at their grounds with amazement and compare them to the ones I saw at the black high schools on the South Coast(of KwaZulu-Natal). I used pictures of those sports grounds as comparative slides when I gave some context to my talks on apartheid education whenever I was overseas. I never thought then that the day would come when it was open to all races or have black teachers, let alone a Principal or Deputy-Principal, so, congratulations, because my heart is singing for you.”

In the year that commemorates the 165th anniversary of 152,184 indentured workers arriving to their African homes in 1860, sadly, Nithianathan and many of our indentured ancestors are not able to witness the fruits of their labour, having sown seeds ready for the next generation to harvest.

The toolbox that built Nithianathan Govenders’ home bears witness to the resilience, toil, and perseverance that Professor Goolam Vahed implores us to write about in “giving voice to the perspectives of ordinary men and women who in the past were neglected or suppressed for one reason or another”.

Selvan Naidoo

Image: File

Selvan Naidoo is the great-grandson of Camachee, indentured no. 3297, and the co-author of the Indian Africans together with Paul David, Kiru Naidoo and Ranjith Choonilal, available at madeindurban.co.za

Related Topics: