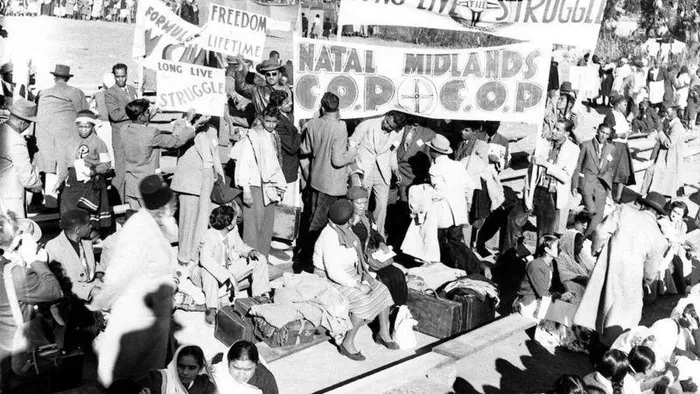

Ladies from various community groups at Kliptown.

Image: Supplied

AS SOUTH Africa, this Thursday marks the 70th anniversary of the Freedom Charter, adopted on June 26, 1955, in a defiant gathering in Kliptown, Soweto, it is timely to interrogate its legacy not with nostalgic reverence but with the sharp lens of critique.

The Freedom Charter was born of a radical imagination. The activists gathered there dared to envision a non-racial, non-sexist, democratic, prosperous, and egalitarian country. It remains the cornerstone of our nation’s constitutional democracy and its rights-based ethos. Yet, this document, hailed as a beacon of liberation, casts a long shadow over a society fractured by enduring inequalities, where the widening gap between rich and poor mocks the charter’s lofty promises.

To reflect on this milestone is to confront the paradox of a nation that celebrates its democratic triumphs, while wrestling with the reality of unfulfilled aspirations. The Freedom Charter was no mere political manifesto. It was a subversive act of collective dreaming, woven from the aspirations of the African National Congress (ANC), South African Indian Congress (SAIC), Coloured People’s Congress, and Congress of Democrats.

South Africans of Indian descent, in whose veins ran a century of resistance against colonial indignities from indenture to segregation, were integral to this tapestry. Activists like Swaminathan Gounden, a worker from Durban’s industrial heart of Jacobs, embodied the courage of the marginalised. At great peril, Gounden slipped through the apartheid state’s surveillance to attend the Kliptown gathering, a journey fraught with the risk of arrest or worse.

The Congress of the People was organised by the National Action Council, a multi-racial organisation that later became known as the Congress Alliance. It was held in Kliptown on June 26, 1955, to lay out the vision of the South African people. Swaminathan Gounden was one of the Natal delegates who attended the Congress under the leadership of Archie Gumede.

Image: Swaminathan Gounden Collection

His return to Faulks shoe factory was met with swift retribution - dismissal for daring to dream of a world where “the people shall govern.” Such sacrifices were not isolated. Among the apartheid regime’s repressive responses was the 1956 Treason Trial, preceded by lightning arrests that ensnared 156 activists, including Chief Albert Luthuli, Nelson Mandela, and Indian African stalwarts like Monty Naicker, MP Naicker and Kay Moonsamy.

The trial, intended to smother dissent, instead amplified the Charter’s rousing call, exposing the moral bankruptcy of a system that equated the fight for social and economic justice with treason. Since 1994, South Africa has drawn on the Freedom Charter’s lofty promises, enshrining its principles in the 1996 Constitution - a document lauded for its progressive ideals such as an independent judiciary, a vibrant civil society, freedom of faith, and the dismantling of racial hierarchies.

Indian Africans, once relegated to the margins in the obscene racial pecking order, have carved spaces in the nation’s political and economic fabric. Census data points to the fact that people of Indian origin have been net economic beneficiaries of the democratic state on a scale second only to those of European descent. Yet, this narrative of progress is haunted by a brutal truth - South Africa is among the world’s most unequal societies, its Gini coefficient a statistical indictment of a dream deferred.

Delegates from Natal at Kliptown for the signing of the Freedom Charter.

Image: Supplied

The opulence of Zimbali’s villas stands in sharp contrast with the squalor of Cato Crest’s shacks. Unemployment, officially upwards of 32%, ravages black youth especially, while land reform and wealth redistribution, which were central demands of the Freedom Charter, are caught in bureaucratic red tape and elite capture. The ANC, once the standard-bearer of liberation, is being suffocated by corruption. Its moral authority has been eroded by governance failures that have left the “born-free” generation grappling in large part with economic despair.

Should today’s youth honour the sacrifices of Goonam, Gounden, Luthuli, and that golden generation? Young peoples’ discontent has been channelled into movements like #FeesMustFall, which echo the Freedom Charter’s demand for accessible education. Yet, others, burdened by the immediacy of survival, dismiss the Freedom Charter as a relic, its promises hollowed out by a post-apartheid state that has traded revolutionary zeal for compromises with traditional and new elites.

Struggle veterans, Judge Thumba Pillay, from left, Kay Moonsamy, and Swaminathan Gounden at the Passive Resistance Monument marking the occasion of the 60 anniversary of the Freedom Charter.

Image: Kiru Naidoo

Social media is a vocal outlet for their disillusionment, with hashtags demonising political and economic grandees. This generational rupture threatens to sever the connective tissue between the struggle’s heroes and a youth population that feels betrayed by the very democracy they inherit. The state has failed to translate constitutional rights into tangible material benefits. There has instead been an inordinate focus on the burgeoning (and unsustainable) social welfare system as a breathing valve to hold the poor at bay.

Judge Albie Sachs with delegates from the South African Indian Congress SAIC at Kliptown.

Image: 1860 Heritage Centre

To read the Freedom Charter in 2025 is to ponder a text that is both prophetic and accusatory. It prophesied a South Africa free from apartheid’s straitjacket, a vision partially realised in the nation’s democratic stability. In a world convulsed by war from Ukraine’s battlefields to Gaza’s ruins to the Congo and Sudan, South Africa’s upholding of the rule of law and constitutionalism is no small feat.

Yet, the Freedom Charter also chastises with its words, translating into a mirror reflecting the nation’s failure to bridge the gulf between rich and poor. The struggles and sacrifices of those who fought for freedom compel us to ask - what does it mean to honour a struggle when its fruits are so unevenly distributed?

Hope lies not in blind optimism but in the radical act of reimagining the Freedom Charter’s possibilities. South Africa’s people must reclaim the courage of Kliptown - its defiance, its unity, and its insistence on justice to forge a future where the people truly govern.

Selvan Naidoo

Image: File

Kiru Naidoo

Image: File

Selvan Naidoo and Kiru Naidoo are co-authors with Paul David and Ranjith Choonilall of The Indian Africans, published by Micromega and available at www.madeindurban.co.za.

* The Gandhi-Luthuli Documentation Centre at the University of KwaZulu-Natal will host a commemoration of the 70th anniversary of the Freedom Charter with the launch of veteran activist Saro Naicker’s biography, Love for Learning, at 6pm today (June 26) on the Westville campus.

** The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of IOL or Independent Media.

Related Topics: