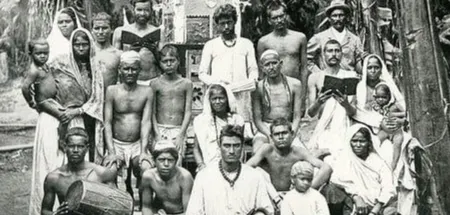

Indians displaced by indentured labour, a human desire for a homeland with a sense of belonging.

Image: commonwealthfoundation.com/

THE stories of hardship, abuse, discrimination, rape, murder and racial violence against Indians displaced by indentured labour have not eroded with time.

The living conditions of Indians displaced by indentured labour under colonial rule, dating back over 165 years ago still prevail today, this time under a new administration. The oppression and suffering imposed on Indians by the colonial rulers are now being dispensed by the indigenous majorities of countries in the post-colonial era.

The indigenous majorities who are now in power and liberated see Indians who are descendants of indentured labourers as foreigners. Most Indians have lived in these countries for more than three generations, which they now call home, and many have proactively participated in the liberation struggles of these countries.

In the mid-1800s, with the changing laws in Europe surrounding slavery, plantation owners in British colonies worldwide had to devise new ways to circumvent the law and acquire cheap labour to maintain high profits. Their innovation led them to the concept of bonded contracts, which came to be known as indentured labour contracts. In reality, this was contractual entrapment for Indian labourers who were not versed in the English language; as a result, their lives were turned into slavery under this contract.

It has become necessary in modern times to address and rectify the perceptions of the past on indentured labour, as it has significant importance in correcting the injustice of the past and the present regarding Indians displaced by indentured labour. The term indentured labour needs to be redefined from one of the labour contracts to one of slavery as experienced by Indians displaced from India to work in foreign countries.

Technological advancements have brought new developments that connect Indians across the globe, each sharing their history via social media about the challenges faced by their communities from Trinidad and Tobago to South Africa to Fiji. Indians living in all post-colonial countries face marginalisation, discrimination and persecution as minorities, often targeted under the guise of crime and perceived as soft targets.

In addition, history shows further victimisation with race-based riots, as seen with the Indo-Guyanese rioting in 1962 and the attack in 1987 on the Indo-Fijians, as rioting erupted with violence and unrest towards Indians. The Indians living in South Africa suffered three riots, namely the 1949 and 1985 Inanda riots and the latest in the KZN 2021 riots.

The trend of discrimination and persecution by race is all too familiar to Indian descendants of indentured labour, as they remain continuous targets. Often, they are perceived as favoured communities by white rulers due to their determination to self-improve and their investment in their community, as well as their business success.

While the self-realisation trend on discrimination and persecution globally among Indian descendants of indentured labour is slow and mobilisation to address it is even slower, there is a growing movement that is slowly gaining momentum as communities connect across the world to share their similar stories and experiences.

Some countries, like South Africa, experience ethnic violence against Indians every 36 years.

Together with government policies such as Broad Black Base Economic Empowerment, which was initially implemented at the birth of democracy as a recourse to address the imbalance of the past, it now serves as a mechanism to advance the interests of the majority, with race over merit to meet this discriminatory policy’s targets. The policy places minorities at a disadvantage, including Indians.

The enforcers of the policy at strategic levels drive personal political agendas to maintain political party dominance over the country by displacing Indians to remote areas in the country to prevent Indians from becoming a majority on a provincial level, which can impact government control and counter their political agenda. The strategy is to keep minorities as minorities on a provincial level to maintain national political control.

Sadly, most Indians are unaware of secret race and politically based fraternities that control the South African environment and exclude Indians from fair social and economic participation. The greatest threat to Indians in South Africa is those from within the community itself, those with business, political or socialite aspirations who align themselves within circles of the majority for self-benefit, some through corrupt political relationships.

They often sabotage any cohesion efforts among Indians, acting as proxies to divide and conquer, thus preventing the Indian community from mobilising and gaining a political voice. In the event of racially incited rioting, these elitists have both the political connections and the financial means to evade violence by leaving the country, while the majority of Indians will be left to face the brunt of the turmoil ahead.

The British enjoyed over a century of financial gain, exploiting Indians both in India and colonies across the globe. While they take a deliberate position to ignore the past suffering or not recognise the current plight of Indians in their displacement regions, they also fail to address the issue by not taking responsibility regarding reparation or making provision for a homeland to accommodate this marginalised and discriminated community.

The target population should be clearly outlined to eliminate immigration opportunists from other countries; only Indians displaced by indentured labour and migrants (free passengers and traders) pre-1947 of India’s independence are to be considered under this programme. Only individuals identified as Indians (both parents classified as Indians) are considered the target population.

An application was submitted to the British High Commission in Pretoria on February 20, 2023, by a small group of activists. While the group possesses confirmation of receipt of the documents, the British High Commission in Pretoria has completely ignored the application. We have many Indian academics and aspiring political leaders; have any of them considered the future of Indian descendants displaced by indentured labour? Do we leave the trend of decades of racial persecution, marginalisation, and discrimination unchallenged for future generations to face as minorities? Or do we take a bold step, stand up and bring change?

A progressive solution would be to create an organisational platform for an interactive discussion between these communities worldwide. Later, in consultation with the United Nations and the countries responsible for the displacement, to explore the feasibility of a homeland within the commonwealth where Indian descendants displaced by indentured labour can relocate and become a sizable community and no longer be regarded as a minority group facing periodic racial persecution and discrimination.

Vinesh Selvan

Image: File

Vinesh Selvan is a military historian and a former SANDF soldier. He also served as business development executive in the South African Arms Industry. Selvan is currently documenting the military participation of Indians in South Africa spanning from the Anglo-Boer War to present day.

** The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of IOL or Independent Media.