Indian and African marriages during the system of indenture and beyond: 1860 to 1954

Inter-racial

Indian African descendants in Reunion.

Image: Supplied

MARRIAGE between Indian indentured migrants and indigenous women in colonial South Africa has never been the subject of a historical study. Equally understudied are the children born of these mixed unions that challenge racial categorisation and identity in South Africa.

In the colonial archive exist understudied examples of intercaste, interracial, and interreligious unions. An intriguing case of such a union, mined from the Natal Native Court Archives files, found Nomgcibelo Hlengwa guilty of murder.

Nora Zwane, the daughter of Hlengwa, resided in the Sawoti Police District of Umkomaas. Nora was estranged from her husband, living apart for more than six months. In her testimony, Nora related that she gave birth to a female child in March 1953, revealing that this was an illegitimate child and that the father was an Indian male.

Hlengwa was present at the birth of the child and over the following few days had questioned her daughter, Nora, about the ethnicity of the child’s father, commenting that the child’s hair was not that of a "native". Two weeks later, Nora was questioned by her estranged mother-in-law and the Induna’s wife about the nationality of the child, which she explained was Indian.

Interracial unions were evident in colonial Natal.

Image: 1860 Heritage Centre

Nora’s mother, Hlengwa, asked her what she was going to do with the child, seeing that its father was Indian. Nora exclaimed that "the child was mine (Nora’s), whether it was an Indian or anything else".

The accused, Hlengwa, then asked how she (Nora) could say that the child was Indian and that she was going to kill the child. Later that night in the hut, Nora related how Hlengwa (her mother) placed her right hand at the top of my baby’s chest and pressed her thumb and index finger on each side of the windpipe.

"I turned my back on what she was doing and started to cry."

The baby died that morning and was buried in a shallow grave. The post-mortem report concluded on the 24th March 1953 revealed that the child had died of shock and trauma to the heart and lungs.

On 20 July 1953, the Native High Court found Nomgcibelo Hlengwa guilty of murder with a penalty of £25 or two months in prison.

East Indian interracial unions in the plantation.

Image: 1860 Heritage Centre

The case of Nora Zwane reveals uncomfortable truths across the colour line in accepting children from interracial unions. Forty-two years after the system of Indian indentured labour recruitment was abolished in South Africa in 1911, descendants who found love beyond their phenotype were faced with prejudice, shame, and murder. Outside of the interracial unions for love, lust, or circumstance, further transcripts in the archive reveal more spurious information on interracial marriages embedded in a letter to the Assistant Secretary of the Native Affairs department dated 8 June 1906.

The correspondence focuses on the intermarriage of Indians and Natives, discussing the marriage of Indian David Soloman, who was born in Natal, to a certain Cape woman. The Registrar of Asiatics noted that "from my experience of the lower classes of the Indian Community, I consider that the marriage tie is very lightly regarded, and that it would be extremely dangerous to make any exception to the restrictions provided for in the paragraph which Clause 2 of Law 3 of 1897 in this respect".

Law 3 of 1897 in the South African Republic (Transvaal) prohibited marriages between whites and people of colour. In July 1906, a letter addressed to the Honouree Secretary of the Mahomedan Committee of Pretoria by the Protector of Asiatics revealed that "… certain Pathans in the Transvaal have taken as wives, native girls of this country. So far as I am aware, the marriages have not been registered under the laws for coloured persons. The women embrace the ‘Mohomedan’ faith and their position is, practically, speaking, that of a mistress."

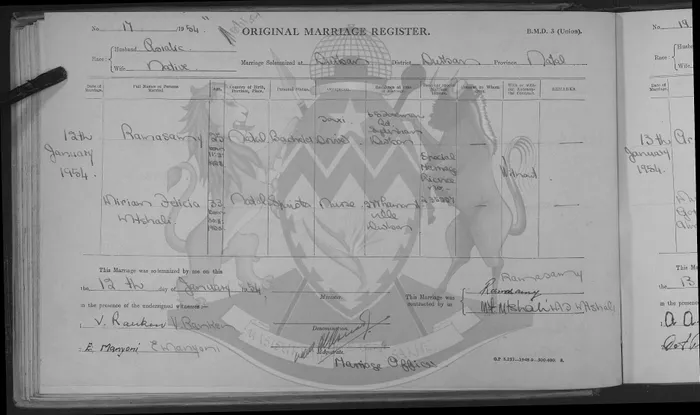

Special Mixed Marriage register of Ramsamy and Mtshali, 1954.

Image: Supplied

"It was further brought to notice that a Mahomedan Indian had applied for a certificate to enable him to marry under the laws in question, a native girl, and as understood that a mixture by marriage with the lower race is repugnant to the feeling of your community."

The Protector of Asiatics goes on to ask the Mahomedan Committee secretary, “I shall be obliged if you (the secretary) will be obliged if you will kindly furnish me with your view on the question (of mixed marriages)."

Further correspondence on the reasons for the marriage of Indians with native women is highlighted in file no 4198 from the Colonial Secretary’s Office. The minute paper brokered the concern that, under a recent decision of the Supreme Court, property may be held by a Native in the country. This provision will, in all likelihood, be used by a large number of Asiatics to overcome their difficulty concerning tenure of property.

They have merely amalgamated (with native girls) to register their property in the wife’s name. The secretary writes that "at least half of the Indians in the Transvaal can marry Natives without violating religious custom, and he considers that the social effects of such a mixture would be deplorable".

"These marriages of convenience were precipitated under laws that disallowed Indians in the Transvaal from holding property, and to evade the law, Indians may endeavour to take advantage of the privilege enjoyed by Natives of acquiring land under their right, by marrying Native women with the object of acquiring title."

Beyond South Africa, in unpacking interracial unions during the system of indenture, Daphné Budasz in her seminal paper titled, Brown men, Black women, White anxiety Indian migration, interracial marriages and colonial categorisation in British East Africa argues that unlike South African and even though the colonial administration did not act directly against these interracial relationships, the offspring of these unions represented a potential challenge to the colonial order.

“Besides the fact that interracial couples resisted the colonial division of races and British divide et impera political strategy, the existence of ‘mixed-race’ children was disruptive, because it made visible the irreversibility of Indian settlement and challenged land ownership patterns in favour of White settlers.”

Audra A Diptee argues in her paper Indian Men, Afro-Creole Women: "Casting" Doubt on Interracial Sexual Relationships in the Late Nineteenth-Century Caribbean that "there were structural factors, such as residential separation, for example, which limited social interaction".

She argued that scholars have overlooked the perspective that "Afrocreole women had a decisive role in negotiating sexual relationships - interracial or not - and this was influenced by the earning power of potential spouses, existing stereotypes, and cultural differences".

Suriname scholar, Madhvi Ramautar, who is presently researching interracial Hindustani (Indian) marriages in Suriname from the period of indentureship in 1873 to the present, writes that interracial marriages are not a strange phenomenon in Suriname. Before the arrival of the Hindustanis, interracial marriages were present in the Surinamese community. After the arrival of the British Indian immigrants in 1873, interracial marriages were also entered into with the other ethnic groups due to the lack of women. Ramatautar notes that mixed Hindustani couples were and still are confronted with rejection and discrimination within their family.

Brian L Moore’s "Cultural Power, Resistance, and Pluralism: Colonial Guyana, 1838 - 1900 in Guyana” revealed that immigrant Chinese men established sexual relations with local Indian and Creole women due to the lack of Chinese women migrating to British Guiana. More common in his research, Moore expresses that more Indian women and Chinese men establish sexual relations with each other, and some Chinese men often took their Indian wives back with them to China.

In Guyana, while marriages between Indian women and black African men are socially shameful to Indians, Chinese-Indian marriages are considered acceptable. "Chiney-dougla" is the Indian Guyanese term for mixed Chinese-Indian children. The term "Dougla" emerged in Trinidad and Tobago to describe individuals of mixed Indian and African descent, highlighting a distinct mixed-race identity that challenged colonial racial categories.

During Indian indenture in various countries, interracial marriages and relationships, particularly between Indian indentured workers and other groups like Africans, were common, although often undocumented and stigmatised. These unions were often driven by the significant gender imbalance within the indentured population and the need for companionship and support in a new and challenging environment that deserves more scholarly attention in telling the fuller story of indenture in South Africa as we commemorate the 165th year of the first indentured passengers arriving to South Africa on 16 November 1860.

Selvan Naidoo

Image: File

Selvan Naidoo is the great-grandson of Camachee, indentured no. 3297, and director of the 1860 Heritage Centre.

** The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of IOL or Independent Media.

Related Topics: