The memories of diaspora: a South African family story

Cultural tradition

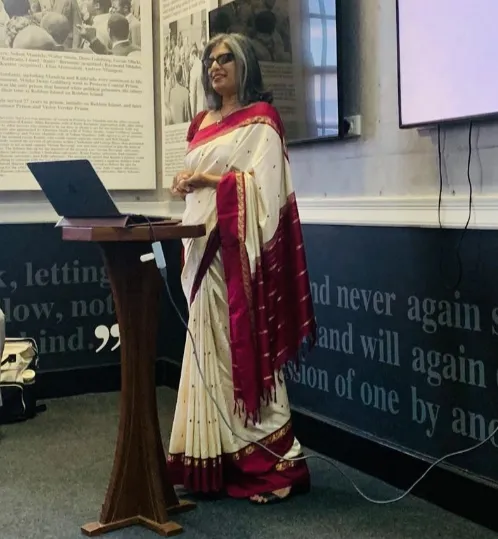

Vilashini Cooppan with her mother dressed in a sari

Image: Supplied

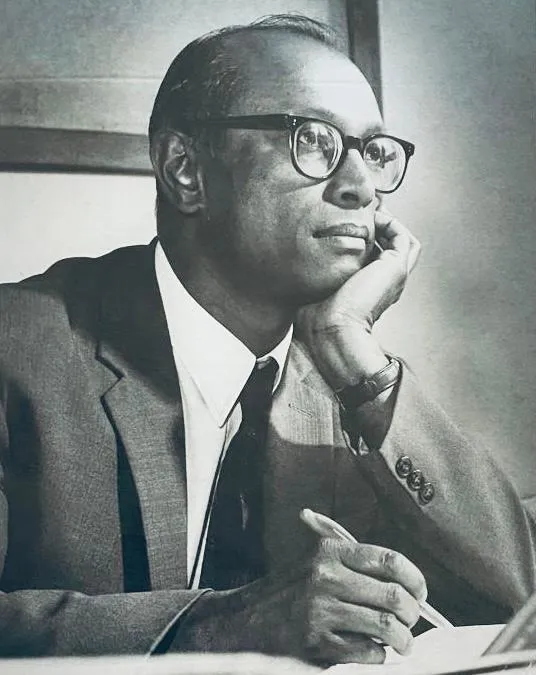

Professor Vilashini Cooppan is the granddaughter of Dr Somasundaram Cooppan, who was among the first three students to matriculate from Sastri College in 1930. He was a British Council Scholar at the University of London’s Institute of Education and completed a PhD in Education at UCT in 1949. Somasundaram taught at Sastri College, Springfield Training College, the Presidency College in Triplicane, Madras, and Macquarie University in Australia. He subsequently joined the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa and was based in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. His son Ramachandra, Professor Vilashini Cooppan’s father, also matriculated from Sastri College and studied medicine at the University of Natal, before doing a Fellowship in Diabetes in the United States and joining the Joslin Diabetes Center in Boston, and being appointed Clinical Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School. Below is an extract of a lecture delivered by Professor Vilashini Cooppan at the 1860 Heritage Centre last Sunday.

WE IN SOUTH Africa are the descendants and inheritors of the Indian diaspora. To inherit is to be given a gift, indeed many gifts: the riches of culture, history, tradition, memory, family, community, love. To be inheritors is also to be time-travellers, to live simultaneously in the present (here and now); in the past (the places and people we came from), and in the future (the unfolding of what we are becoming, people both old and new).

Diasporic becoming happens over and over again.

First, leaving the homeland, and second, creating new homes, new ways, new lives, that bind a community in multiple ways, within itself, to its new land and that land’s people and histories, and also to the memory of the homeland. We here are Indian by ethnicity, like one and a half billion people on the planet.

We are South Africans, part of this country’s ethnic and racial mix, sharing the land and the nation, our rights and our futures with black Africans, with so-called coloureds, with whites, both English and Afrikaner, and with new migrants from elsewhere in Africa and Asia. And finally, we are South African Indians, a thin, unique piece, torn from the Indian diaspora’s round roti.

Professor Vilashini Cooppan

Image: Supplied

The word "diaspora" means the scattering of peoples like seeds, roots, airborne, and falling to the earth to germinate in new soils. Here in South Africa, we are situated at the continent’s tip, where at Cape Point the Atlantic Ocean meets the Indian Ocean, those two great world-systems of centuries, for the Indian Ocean world, millennia, of trade.

Well before Western imperialism, the Indian Ocean World was a zone of circulation.

Noun. 1. Movement to and fro or around something, especially that of fluid in a closed system … similar: flow, motion, movement, course, passage.

The noun circulation invites verbs: flowing in a closed circle or circuit, like blood in the body or sap through a sugar cane plant or goods in an economy built on them; encircling, as a border might if the unity it contained was also porosity; pouring, as in something that exceeds the containers that would catch it, like holds that spill forth and things that come in waves - ships, slaves and indentured labourers, migrants, cultures, histories, memories.

Stacks and sacks of pearls, cowrie shells, cloves, cinnamon, sugar, tea, opium, rice, cloth; bulk goods and luxury objects, the stuff of the Indian Ocean world, the material history of so many peoples, including our South African Indians of the diaspora.

Dr Somasundaram Cooppan

Image: Supplied

In our house in Wellesley sits a round brass pot. It has been there for as long as I can remember. It belonged to Amma and Amma’s mother before her, and maybe even to Pati’s Amma. At some point, perhaps 150 years ago, that pot crossed the Kala Pani, the black waters off the eastern coast of India, along with the other goods, the chappals, the saris and dhotis, the small bags of spices, the rice and okra and eggplant seeds, the brass velkas or prayer lamps and the flash of a bangle’s gold carrying all the family wealth.

There is memory in objects, a dense layering of time so that the dust of the past and the solidity of the present share a single plane. Today, the gold around my neck is my Amma’s pendant, bought in Mombasa on a long-ago visit, and my mother’s wedding jewellery chain. I also wear my Amma’s sari, which she inherited from her own mother.

I wore it the day I graduated from Yale with a bachelor’s degree. My father ironed it the morning before my Ph.D. graduation from Stanford. And a month ago I wore it again, for my son Rohan’s BA and MA graduation from the University of Chicago.

In this sari, I carry the memories of our family’s history, the paths of culture and education that led our grandfather’s father’s father to the work of teaching in the sugar cane days, and our grandfather, Papa, to study in Cape Town, then in England, to become the first non-white person in South Africa to earn a Ph.D. Someday, I will wear this sari when my nephews and niece graduate from college, if I live long enough, and when my own grandchildren graduate from college.

I have worn this sari one other time, in 2015, to give a lecture in Thirunvanathapuram at a conference at the Kerala Women’s College on the senses and the emotions. I remember landing in the monsoon-wet morning at Trivandrum airport, checking into the hotel, crossing the room’s cold white marble tiles aglow with moonlight to open the tall dark cupboards with their slight smell of wet wood into which air heavy with rain has seeped. Showering off the 24 hours of travel and, without really thinking, rubbing in the hotel’s neem body lotion and then dusting my body with the hotel’s sandalwood talcum powder.

And then it hit me. This is Amma’s smell rising from her lace blouses, sweetly lingering in the munthani of her sari. We would smell it when she cuddled us as babies, children and girls, and adults. I entered the conference room still thinking of Amma, the Mysore talc’s white glow on the brown of my skin (did it really, as I’d read somewhere, contain stray bits of ground glass?). Diamonds on skin, moonlight on marble tiles, hints of gold thread lighting up the saris I hung in the cupboards.

I have no saris that are not a little bit fancy. In my diasporic Indianness, saris are for graduations and weddings and births and deaths, for prayers and rituals and ceremonies and parties. And whenever I wear a sari, I remember how much I loved to watch two women tie them, my mother and her sister, both of them so graceful as they moved, wearing the sari as effortlessly as a second skin. I love especially an old sari, one whose pleats fall with the luscious heft of fine old silk, its wearing a recompense for long languishing in a kist or cupboard.

I remember the never-worn-ness of so many of the saris that my mother carried in her steel trousseau trunk from South Africa to Australia to Canada to the United States. The saris I would unfold and admire as a young girl in the afternoon quiet preceding a teatime without visitors, the saris that, in her diasporic loneliness far from home, my mother slowly gave away. Aunties, please don’t get rid of those old saris; they are our history, our memory, ourselves and our ancestors, and our future generations.

That day in Thiruvananthapuram was the first time I wore a sari to give a paper. Today is the second. Then and now, I wonder what happens when I use a sari for thinking.

What Salman Rushdie once called “the migrant’s eye view” is, for all its many tragedies, for all the desperate losses and deprivations and dangers that cause people to leave their homelands, in the end still also a hopeful eye. Because the migrant’s story tells us that in the end, no wall is strong enough to stop cultures from changing, from absorbing differences, from reinventing themselves, from becoming bigger.

We are the children of the movements of many diasporas, of slavery and colonialism and indenture and apartheid, so many histories run in our veins, mix in our blood, along with those new families and cultures we have added.

Vilashini Cooppan is Professor of Literature and Critical Race and Ethnic Studies at the University of California at Santa Cruz.

** The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of IOL or Independent Media.

Related Topics: