Spiritual violence: preying on the praying?

Hidden crisis

A story that appeared in the POST last week.

Image: File

SOCIETY expects priests and religious leaders to possess the highest ethical and moral values, display exemplary integrity, follow a lifestyle in accordance with prescribed scriptures, and provide religious and spiritual support for all followers of their faith, rooted in compassion, humility, integrity, piety, and service.

There has been some justifiable public concern about "spiritual violence" and the inappropriate conduct of priests, and especially their deviation from acceptable ethical and moral conduct. According to the Church of England, "spiritual violence" is "a form of emotional and psychological abuse characterised by a systemic pattern of coercive and controlling behaviour in a religious context".

Regrettably, numerous religious institutions worldwide have reported thousands of cases of clergy sexual abuse in recent decades. In almost all religions and denominations, sexual abuse by priests and trusted leaders in the faith sector have been a grave concern, and many perpetrators may have been wilfully or inadvertently protected by institutional and organisational secrecy.

According to the Abuse Response and Prevention network: “Clergy misconduct includes sexualised behaviour, inappropriate words and innuendo, harassment, threats, physical movement and contact, hugs, kisses, touching, intercourse and emotional and spiritual manipulation. It is a grave injustice toward another person, which violates personal boundaries. At the same time, it violates the entire religious community, because a sacred trust with the congregation has been betrayed.”

On April 2, 2025, all charges against Timothy Omotoso and his co- accused were dismissed.

Image: File

There are well-documented cases in the Catholic Church, and sexual abuse is also a serious problem in other denominations and faiths. Unfortunately, the problem persists because religious organisations appear to be slow or reluctant to take appropriate measures to prevent and respond to clergy sexual abuse, and this is particularly serious in South Africa.

In August 2014, there were allegations of transgressions by a Hindu priest in Chatsworth: “He touched women, embraced them, and engaged in hugging and holding young female devotees, which was not how a priest was supposed to conduct himself.”

In October 2019, a Hindu priest in Gauteng was found guilty of having an illegitimate relationship with one of his married devotees. He was expelled from the Purohit Mundal (Priest’s Council) of the Shree Sanathan Dharma Sabha of South Africa.

Muslim Views (January 8, 2021) carried a report about how a Darul Ulaam teacher had sexually abused a 6-year-old girl.

In an unrelated, courageous Facebook post on May 20, 2025, Zaakirah Mohamed from Lenasia wrote about her experience: “Today, I break my silence for myself and for many, many other girls and women who have fallen as a victim of a ‘HAFIZ’ from Lenz… I am sharing it for justice - justice for myself and for the many other girls and women who have been harmed. I was only 6-years-old when I first fell as a victim of this man’s sick sexual tendencies… This man, cloaked in religious authority, used the image of piety to shield himself.”

The Jamiatul Ulama KZN maintained that “perpetrators, irrespective of who they are, must never be shielded. Those guilty of such heinous acts must face the full consequences of their vile and perverted behaviour".

Since 2003, there have been 33 reported cases of sex abuse by Catholic priests in South Africa. The Archbishop of Johannesburg, South Africa, Archbishop Buti Tlhagale has called for the “immediate excommunication of Catholic priests who have sexually abused minors”.

According to Archbishop Tlhagale: “The halo of the Catholic priesthood has been broken. The church is castigated because it appears to have claimed to have a ‘holier than thou’ attitude. We priests claim to be the other Christ. We have set the bar high but fail lamentably to live up to that moral standard, that moral ideal, hence the merciless and the harsh criticism.”

Timothy Omotoso, a Nigerian televangelist based in South Africa, was arrested in 2017 on charges of human trafficking, sexual assault, and rape, related to his alleged abuse of young women in his congregation. His trial began in 2018 and received extensive media attention because of allegations that Omotoso forced young women into sexual relationships while pretending to provide spiritual or religious guidance.

On April 2, 2025, all charges against Omotoso and his co- accused were dismissed. The judge pointed to inadequate cross-examination and prosecutorial errors as grounds for the verdict. Archbishop Tlhagale said that the sexual abuse allegations against Omotoso, “bring to the fore the raw feelings of anger, of outrage, of bitterness, of frustration, of hatred… betrayal, of disloyalty, of unfaithfulness, of cover-ups, of a sinister abuse of power and deception".

In a submission to the government in June 2017, the Cultural, Religious and Linguistic Rights Commission (CRLRC) expressed concern about the commercialisation of religion and abuse of people’s belief systems, for example, “pastors instructing their congregants to eat grass, snakes, drink petrol or part with considerable sums of money to be guaranteed a miracle or blessing” (in other words, preying on the praying).

The CRL Rights Commission identified several issues in the religious sector in South Africa, including the rise of independent and charismatic churches, ineffective regulations, and a lack of accountability. The challenges of patriarchy in religious and cultural areas include manipulation, threats of violence, fraud and sexual abuse.

The CRL Commission recommended regulating the religious sector, as well as promoting public education and awareness campaigns. However, the counter view in submissions from the organised Christian faith sector was that government regulation would “violate the constitutional rights of freedom of religion, belief and opinion, as well as freedom of association”.

Furthermore, the law applied equally to all, including priests and religious leaders, for example, in cases of sexual abuse. The South African Council of Churches contended that the “church is no sanctuary for criminal conduct… any act of criminality must be referred to the criminal justice system.”

Compromised integrity in religious leadership, such as sexual misconduct, financial fraud, or abuse, can lead to a range of negative consequences, including spiritual downfall, social shame, erosion of community trust, and damage to the religious tradition and organisation.

A critical question is whether religious organisations can regulate themselves? Self-regulation is commonly seen as essential to maintaining the independence and autonomy of religious organisations, allowing them to conduct their internal operations by doctrines, principles, and customs that may be difficult for secular authorities to comprehend or regulate.

Amid mounting concerns over alleged abuse and exploitation by priests, the South African Hindu Maha Sabha has developed a code of conduct to which all registered priests must abide. This code of conduct provides the basis for the professional and orderly conduct of priests, providing an environment for the Hindu community to benefit fully from the services and expertise of affiliated priests. Perhaps the other faith groups should consider following the example of the Maha Sabha?

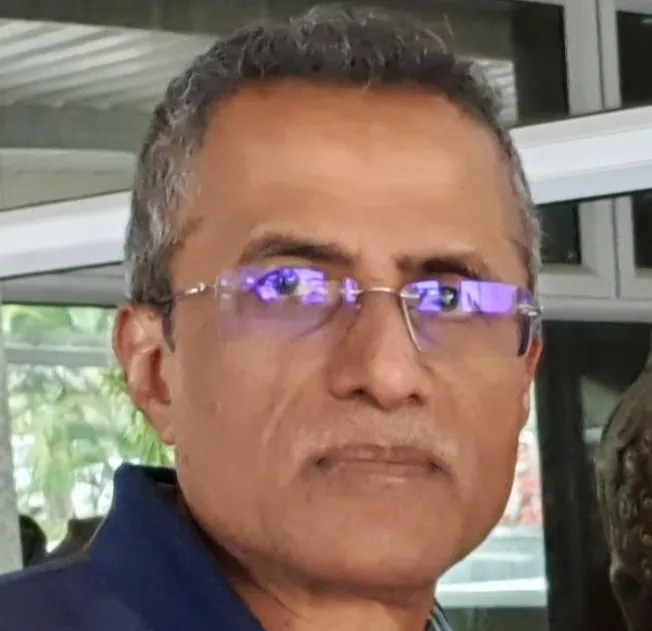

Professor Brij Maharaj

Image: File

Professor Brij Maharaj is a geography professor at UKZN. He writes in his personal capacity.

** The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of IOL or Independent Media.