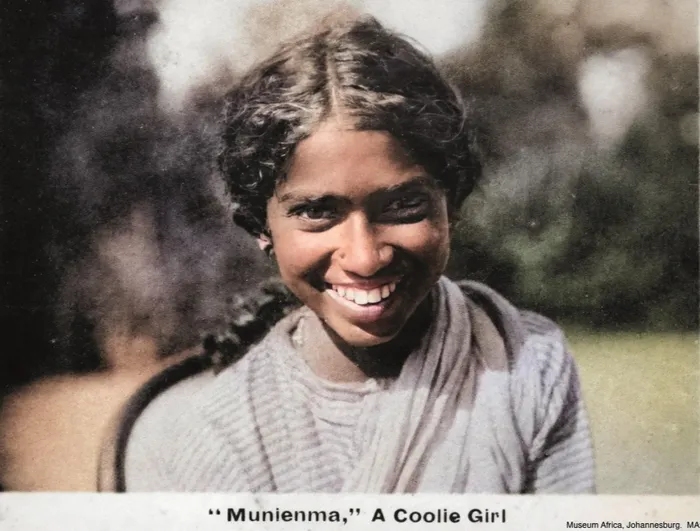

A colonial postcard titled "Munienma," A Coolie Girl.

Image: Picture Credit: Museum Africa, Johannesburg.

THE Native High Court archives hold a transcript that details the trial of Gundwane Sikakana for the murder of "Coolie Mary" in 1914.

The Court transcript describes harrowing details of the murder of 45-year-old Jugrajee, commonly known as "Coolie Mary".

“I knew the Indian woman named Mary and bought eggs and vegetables from her…”

Witness testimony by those involved with the case retold their account of what transpired to "Coolie Mary". The first person to find a murdered Jugrajee was a school boy, “I am the son of William Henry Brown, a platelayer on the South African Railways, living in a cottage, 176 on the town lands, Ladysmith. I remember Tuesday, the 5th August 1913. On that afternoon, when coming back from school, I saw a coolie woman lying dead. I recognised her.

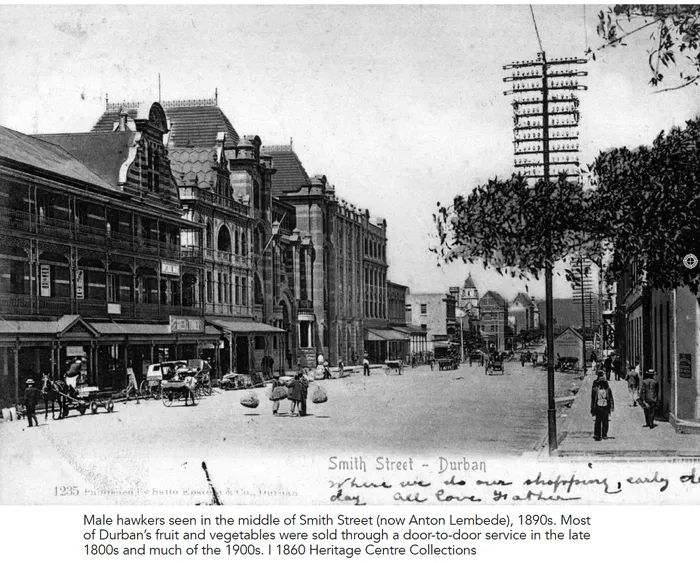

Smith Street, Durban

Image: 1860 Heritage Centre Collections

"She was Coolie Mary. Mary is the name we use for Indian women who sell vegetables. She used to bring vegetables to our cottage… When I saw her lying, she was lying under the trees… I saw a basket and a stone lying by her body.”

Her husband’s testimony revealed that Jugrajee was wearing a pair of bangles, a broach, a pair of leg ornaments, and a nose ornament.

“Those are the articles of jewellery she was wearing. During the day, I received a report that she had gone missing; I went to look for my wife; I went to my brother’s house. I came across my wife the next morning, and I had been to the police. The accused used to live near me; he used to come occasionally and buy bread from my wife, he used to pay cash, but afterwards he bought for credit…”

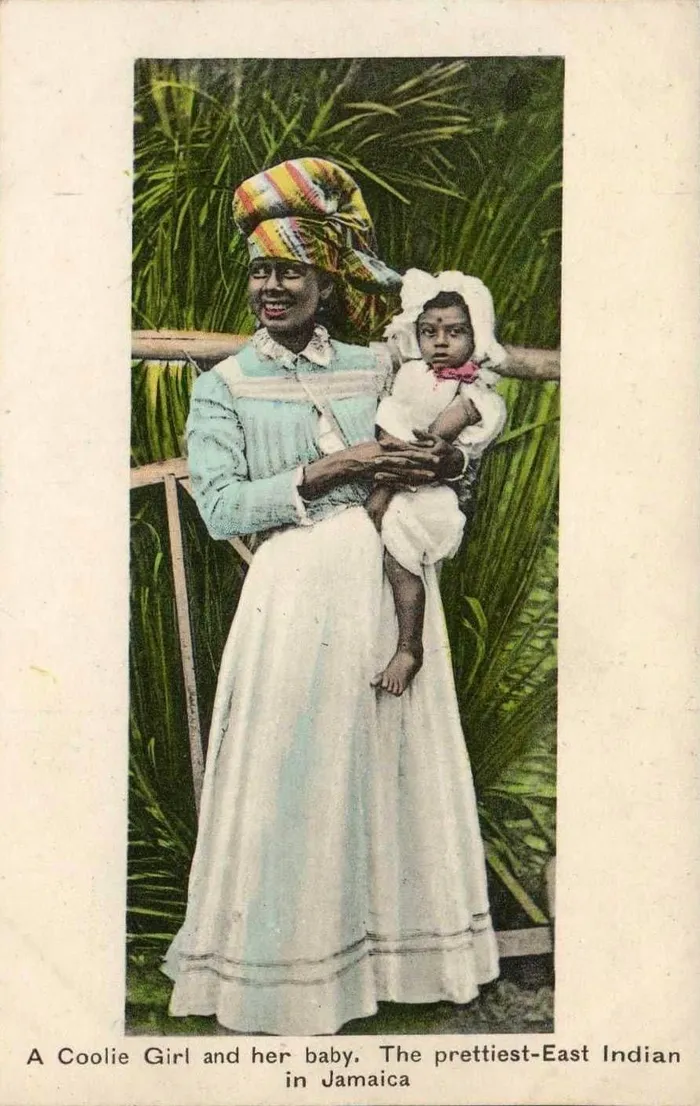

A colonial postcard titled: A Coolie Girl and her baby, The prettiest East Indian in Jamaica.

Image: Picture Credit: Museum Africa, Johannesburg.

Witness testimony revealed that Jugrajee was murdered by Gundwane Sikakana.

“I have known her for about a month; the body was lying on the left side fully extended, there was a wound just below the right eye… The stone was laying about 18” or 2 feet from her head… The head was lying in a pool of blood; there was a basket immediately behind; this is the basket marked A, it contained oranges, matches, and cakes. Nothing was disturbed in the basket; it was just as it was new. Nothing had been stolen from the basket at all… he was pounding and kept pounding, we did not see what he was pounding, but we thought it was a goat.”

The post-mortem report revealed that 45-year-old Jugrajee had died of shock due to the extent of her injuries. Jugraree was killed by Gundwane Sikakana because he owed her money. He was found guilty of murder and sentenced to death. The death of Jugraree foregrounds the fragility of life for the ex-indentured community of colonial Natal in the 19th and 20th centuries.

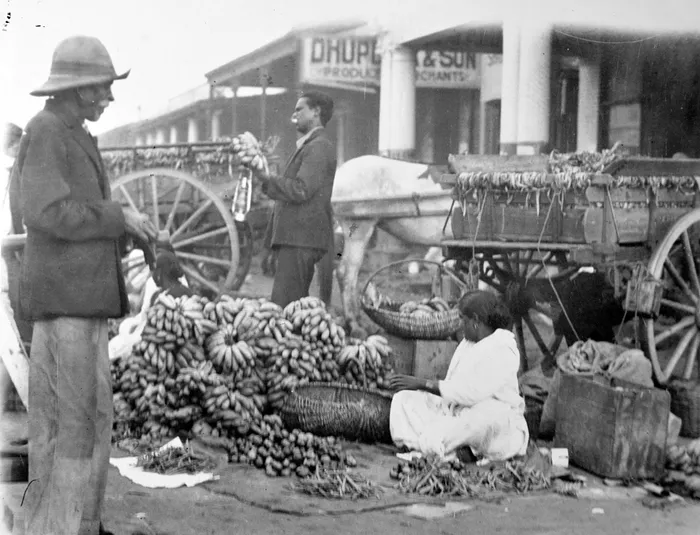

Street Hawker on the Streets of Durban.

Image: Picture Credit: 1860 Heritage Centre

After surviving the brutal system of indenture and in the hope of forging a better life for her family, Jugraree turned to hawking as a means of survival. Her industriousness and hardworking spirit were cruelly snuffed out by avarice in the violent world that Jugraree inhabited.

Like Jugaree, Indian hawkers were a feature of life in colonial Natal as reported in the Wragg Commission of 1885. Eminent scholar of indenture Professor Goolam Vahed’s PhD thesis, The Making of an Indian Identity in Durban 1914 to 1949 revealed a 1909 report on hawking noted that women hawkers, referred to as "Mary" by whites, and male hawkers, called "vegetable Sammy", piled their fruit and vegetables in baskets which they carried on their heads from house to house each day in "rain or sunshine, spring or winter."

During this early period, while white farmers objected to Indian hawkers, white working-class housewives considered this an invaluable service.

A colonial postcard “ A Coolie Girl, Natal.

Image: Picture Credit: SAB SAL

"An Australian lady," for example, wrote to the African Chronicle in 1908 that:

“The Indian hawker is a great convenience, especially to the poor white. A rich lady can roll down to the market in her carriage and purchase her requirements in the vegetable line for the day, but where does the poor woman come in, who perhaps has a child or two to nurse at home, besides having to go through the drudgery of her household duties? To her, "Sammy" and "Mary" is a very welcome sight and a saving of time and trouble. Her marketing is done at the door, and she doesn’t want to hurry and scurry away to make purchases. You can readily imagine what the abolishing of the Indian hawker would mean to the poor people living on the outskirts of the city.”

Mr BD Lalla, a student at Fort Hare and a distinguished teacher at Sastri College, was a poet known for his work on the Indian indentured labour experience in South Africa. He is particularly noted for his poetic trilogy that romanticised the Indian migration to the Natal sugar plantations.

His poetry and folksong served as a commentary on the racial politics of the time. Lalla’s mid-1940s poem suggested the sense of resentment of the name "Coolie Mary" felt by many:

Is my wife a Coolie Mary

And thy a blessed fairy?

Is my wife a Sammy Mary?

Is she in her way contrary?

Why is there this hated difference?

Must thy cup be filled with sweetness

And my own with vileness?

To thy door each bitter morning

Cold or hot or wind-a-storming

Comes she with her breath-a-panting

"Nice fruits, missus, and greens" a-chanting

Is she not a blessed fairy

Doubled as a Coolie Mary?

If you choose to call her Mary

Think of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

Award-winning writer and psychologist Devi Rajab’s mother, Amartham, sang songs in Tamil of hardships faced by the indentured labourers who cried out for mercy as their arms and legs were so full of fatigue at having to slash the cane all day long in the hot sun.

“Have you no heart?” they asked their white sugar barons and their overseers.

“Even a stone would feel our pain. Has the devil resided in your soul for you to be so cruel?”

Later, Amartham tackled the abuse of apartheid with dignity. On one occasion, when she walked into a white butcher shop and was addressed as “Mary” in the derogatory designation of “Coolie Mary,” often given to Indian women, she replied with her head held high: “Can I have a pound of lamb chops, please, Jane?” To which the woman replied, “My name is not Jane,” and she retorted, “Well, my name is not Mary”.

As we commemorate the 165th anniversary of the first indentured workers arriving in South Africa this year, we must acknowledge that the human experience in telling this story is more nuanced than we perceive it to be.

In the words of the greatest historian on indenture, Brij Vilash Lal: “Some tend to reduce a complex (indentured) history to an ideology of grief and grievance for particular purposes, such as seeking reparation (or seeking contemporary political power) from colonial powers that used indentured labour. Some insist on a ‘correct history of indenture’, whatever that may look like.

"These history wars will continue. One hopes that history will not become a branch of heritage study, a subject for veneration and worship, lived experience in a funny costume, but will remain within the realm of reasoned discourse and debate that will do justice to a complex human experience...”

A human experience denied to Jugraree and so many other "Coolie Marys"/

Selvan Naidoo

Image: File

Selvan Naidoo is the great-grandson of Camachee, indentured no. 3297, and the Director of the 1860 Heritage Centre.

Related Topics: