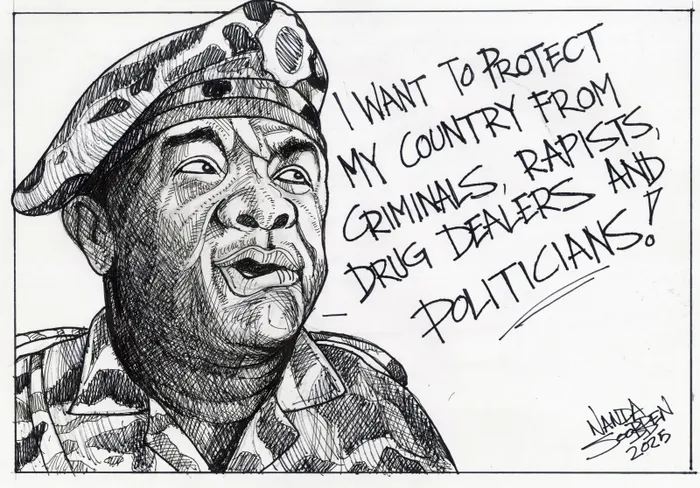

Cartoon

Image: Nanda Soobben

It is now an open secret in South Africa that some people in positions of power engage in unlawful activities such as corruption, bribery, and extortion for purposes of self-enrichment. What makes it common to break the law is that there are rarely any consequences, as culprits often get away with criminality.

Following Lieutenant-General Nhlanhla Mkhwanazi’s spooky claims of collusion between gangsters and those in charge of upholding the law, President Cyril Ramaphosa decided to establish yet another commission of inquiry. The latest commission comes at a time when the findings of the previous ones, such as the Zondo commission, are gathering dust. This explains why many South Africans are growing skeptical of the usefulness of commissions.

Early this month, KwaZulu-Natal’s provincial Commissioner of Police, Mkhwanazi, made very serious albeit not shocking allegations about the rot in the entire criminal justice system, and if one were to stretch one’s imagination, where else does it extend?

In a normal country, Mkhwanazi’s claims would be shocking, but this is the ANC-governed South Africa we are talking about here. In 2010, R4 million went missing from a farm owned by the late former deputy president, David Mabuza. Even President Ramaphosa has a cloud hanging over his head after millions of US dollars, not Rands, were allegedly stolen from his Phala Phala place.

In a potentially disruptive move, Mkhwanazi alleged that the Minister of Police, Senzo Mchunu, and senior law enforcement officers are in cahoots with criminal syndicates. The allegations raise serious issues with regard to the integrity of the entire criminal justice system and the effectiveness of Parliament to hold the executive branch accountable. Specifically, Parliament’s portfolio committees on Police, Intelligence, and Justice appear to have been exposed as ineffective.

One wonders why Parliament has not summoned the Minister of Intelligence, the National Commissioner of Police, and the head of the NPA to shed light on Mkhwanazi’s claims.

The fact that Ramaphosa’s reaction to Mkhwanazi’s claims was slow has made him come across as taking a business-as-usual approach and not appreciative of the grave situation facing the country. Add to his lackluster response to the route he is taking to supposedly get to the bottom of Mkhwanazi’s claims.

This lackluster approach raises broader questions about our leaders’ commitment to the fight against rampant crime, such as corruption, robbery, and murder, that has left citizens living in constant fear.

Lest South Africans not forget, the ANC government was supposed to be the antithesis of its evil predecessor, the National Party government. However, one is increasingly struggling to tell the difference between the greedy ANC leaders and the oppressive National Party government.

What happens if the investigation of Mkhwanazi’s allegations confirms that Mchunu and the deputy National Commissioner of Police, Shadrack Sibiya, are in fact in cahoots with criminal syndicates?

It is becoming increasingly difficult to argue against the notion that South Africa is a kakistocracy-cum mafia state. The governing ANC has presided over the weakening and brazen abuse of state institutions for the self-enrichment purposes of its cadres. Would it be possible then for a self-righteous ANC government to find itself guilty of what amounts to treason here?

In this context, would it be in the interest of the Ramaphosa Administration and, by extension, the ANC for the commission to find Mchunu on the wrong side of the law and thus concede that its deployed cadres in government are in cahoots with criminals?

Let us also not forget that Mchunu is the close ally of Ramaphosa. Mchunu was the most senior ANC leader in KZN to campaign for Ramaphosa when it was unpopular to do so. In fact, Mchunu was the candidate for Secretary General in the CR17 faction but lost the SG position to Ace Magashule at the ANC’s elective conference in NASREC. What this means is that Ramaphosa is unlikely to throw Senzo Mchunu under the bus.

While these allegations remain untested, they help lend credence to the theory that South Africa is not winning the war against rampant crime because those in power may be benefiting from it. In essence, as Barney Mthombothi of the Sunday Times concludes, “Ramaphosa is blithely presiding over a crime syndicate-as-government.” This may explain why the government lacks the political will to act against criminality, such as endemic corruption, bribery, fraud, and political assassinations.

Mkhwanazi, in effect, told South Africans that the country’s national security has been auctioned to the highest bidders. This raises serious questions about what else those in power have auctioned to the highest bidders? Even more concerning is that Ramaphosa appears to be either clueless about the things he should be privy to or does not appreciate the seriousness of our national security. Maybe he needs to be reminded that the buck stops with him

The fact that Ramaphosa did not dismiss Mkhwanazi’s allegations as speculation and hogwash says an awful lot about the seriousness of these untested claims. However, establishing commissions of inquiry has not resulted in the successful prosecution of those breaking the law. Lest we forget, acts of corruption and getting away with it in South Africa have been normalised.

As usual, Ramaphosa thinks a commission of inquiry is the best way to establish the authenticity and veracity of Mkhwanazi’s claims. As the nation waits for the investigation(s) to establish the facts, it is not inconceivable that there is the real possibility of a de facto Mafia state in post-apartheid South Africa.

Even some senior ANC leaders have acknowledged the close links between the ANC’s NEC members and criminal syndicates. Jackie Selebi, then the National Commissioner of Police, stunningly and arrogantly declared at a press conference that Glen Agliotti, a reputed drug lord, was “my friend, finish and klaar.” Agliotti even bought shoes for then-President Thabo Mbeki.

Then there was the Minister of Social Development, Bathabile Dlamini, who brazenly declared that every ANC NEC member has skeletons in the closet in an attempt to defend then-President Zuma, a poster boy for corruption.

For his part, Zuma has repeatedly threatened to spill the beans since his dismissal as the Deputy President of the country. He has even gone as far as saying that if he goes down, he won’t go down alone. Excuse me, doesn’t that sound like a man full of guilt but also knows he is not the only guilty party in the sea of ANC corruption?

In 2021, Zuma’s supporters ran amok after he was imprisoned for being in contempt of the Constitutional Court. The 2021 riots laid bare the weaknesses of South Africa’s Intelligence and Police services. More than 300 people lost their lives, and the economy lost billions of Rands. After telling the nation that the state had identified 12 instigators or masterminds of the 2021 riots, Ramaphosa has, to date, not named even one instigator.

Another weakness of the two services was exposed during the Marikana massacre. In both situations, the Police and Intelligence services were caught sleeping on the job.

Mkhwanazi’s bombshell that criminal syndicates have infiltrated the law enforcement agencies echoes the sentiments of Advocate Shamila Batohi, the head of the NPA. Just last month, Batohi, raised similar concerns about criminals infiltrating the prosecution's authority. The Minister of Justice, Mmamokolo Kubayi,, fearing that South Africa’s image could be tarnished, convinced Batohi to withdraw her serious allegation.

With South Africa’s national security compromised, some citizens and businesses are relying on private security companies to protect them. No wonder the private security industry is now one of the fastest-growing sectors of our economy. Families that can afford alarm systems and businesses are investing heavily in security, because they have figured out that they are on their own.

Then there are rising cases of mob justice and people taking the law into their own hands among the poor. Today, every South African lives in fear of being a victim of crime. Could it be that people are resorting to mob justice because they have lost confidence in the inept and corrupt Police?

Then there are people who are charging protection fees in the absence of credible police officers. No wonder South Africa is struggling to win the war against rampant crime and lawlessness. Almost every citizen has been a victim of crime, or they know people who have been victims of crime.

What then are the chances that the ANC will survive the 2026 elections?

Zakhele Collision Ndlovu

Image: File

Zakhele Collision Ndlovu is a political analyst at the University of KwaZulu-Natal.

** The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of IOL or Independent Media.

Related Topics: