Kanjikeerai, a marker of acculturating identity

Food culture

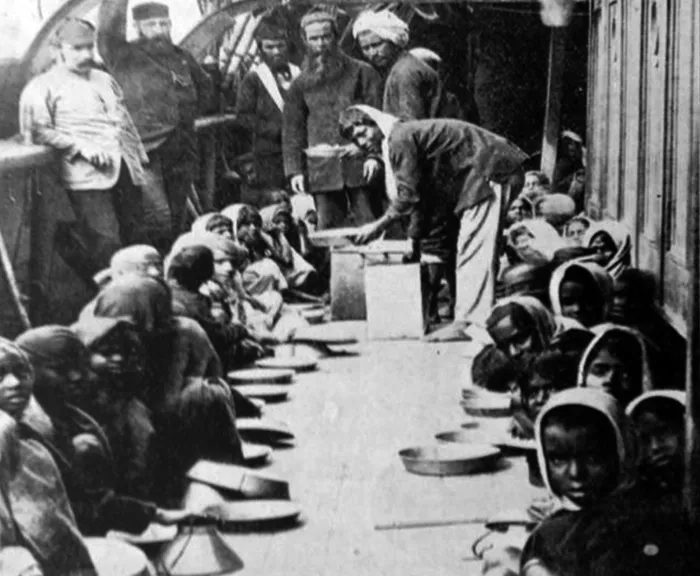

Children being fed on board Ships of Indenture early 1900s.

Image: 1860 Heritage Centre

Kanjikeerai is a staple meal in the homes of many descendants of Indian Indentured workers living in South Africa. A delicious meal blending a cacophony of flavours from pungent to sweet, sour, bitter, and salty, it is further embellished with a crumble-like tactile texture of crispy fried dried fish. Made with the water-lily type Itebe herb, which is popular among the AmaZulu culture in KwaZulu-Natal, kanjikeerai is a marker of acculturated identity.

The food culture of the system of indenture makes for interesting reading. It is an area of focus that marks a lacuna in the historiography of indenture.

Professor Ashutosh Kumar of Banaras University fills this gap with a seminal study called Feeding the Girmitya: Food and Drink on Indentured Ships to the Sugar Colonies.

Kumar’s paper gives phenomenal insight into the food of the indentured passengers on the sea voyages during the 18th and 19th centuries, drawing on archival records of food rations found in the ship logs as well as oral testimonies of girmitiyas’ autobiographies by Baba Ramchandra and Totaram Sanadhya from Fiji and Munshi Rahman Khan from Surinam.

Itebe herbs

Image: Supplied

Professor Kumar notes that “by the 1880s, many labourers traveling on the colonial ships had begun to complain to officials about the foods they were issued on board. For instance, some of these emigrants demanded rice, while others insisted that chapatis be provided to satiate their hunger during the long sea voyage. The colonial office investigated this debate over starch and sustenance. Such dietary negotiations positioned the labour ship as a unique space within Indian colonial society; yielding to individual tastes and regional identities, this new space was free from the caste rules that typically governed dining practices in the subcontinent”.

In his biography titled Jiwan Prakash, Munshi Rahman Khan, an indentured labourer in Surinam, maintained that it was not possible to maintain the caste hierarchy of eating under the indenture system.

Kanjikeerai with Karuvadu (dry fish)

Image: Supplied

Khan gives a detailed description of the food that indentured workers received during their journey from the countryside to Calcutta, at the port of embarkation, and then on the sea voyage. He acknowledged that until reaching the central coolie depot at Calcutta, indentured laborers received raw food material and prepared their own food, maintaining all caste and hierarchical differences; once they reached the Calcutta depot, however, they had to forget caste and hierarchy while dining.

Khan writes: “Till we reach here [Calcutta], we were allowed to cook our own meals as we pleased, as we were given raw food materials. Everyone followed his own rituals and systems. They wore their Janeu (sacred thread), tikka (forehead mark), Kanthi Mala (sacred necklace), etc., according to her/his caste and religion, and followed the system of caste and creed. They had managed to preserve their religious sanctity.”

Sour Dhall, green beans and potato.

Image: Supplied

Beyond the kala pani (dark ocean waters), the study of food culture on the plantations where workers were indentured receives even limited scholarship, except for writing on Murungakkai keerai and its entangled human connectivity with a study titled Greener on the other side: tracing stories of amaranth and moringa through indenture by Pralini Naidoo.

On the plantations, dhall, rice, and salted dried fish were the agreed ration for Indentured labourers while they toiled on the sugarcane plantations. In Natal, plantation owners substituted rations with cheaper ingredients that were foreign to workers. Mielie meal was substituted for rice, and more than often, food rations were withheld for the slightest infringements, leveraging power for increased labour production.

Khichdi with potato curry.

Image: Supplied

Learning to adapt to a foreign land, these labourers learned how to incorporate African food ingredients like maize meal and amadumbe to make their meals palatable. For them, little was enough for a feast. Immediately after the beastly exercise of quarantine, indentured workers were shepherded to plantations very often fifty to a hundred miles away. The terrain and vegetation were different from those that they encountered in either the Southern or Northern parts of India.

Their basic meals came in the form of rations that included dhall and rice or mielie meal. Rations sometimes arrived late or not at all, forcing people to forage in the forest, picking all varieties of herbs, fruit, and tubers. The tasty yam called amadumbe was boiled, roasted, or curried. Similarly, green bananas became fritters or grated as a curry. Mangoes could be curried either sweet, sour, or pickled.

Gem squashes take form as a deceptive substitute for meat or fish, especially when soured with tamarind or green mangoes. Rice, which is a staple throughout Asia, was in short supply. Indians made amends. Mealies were pounded into fine grains. When slow-boiled, it looked very much like rice with mielie rice Khitchdi being a firm favourite, even amongst present-day descendants of indentured ancestry.

Sometimes turmeric or tamarind was added to vary the flavour. With meat either being very expensive or entirely out of reach, salted and dried fish added to a tomato chutney became a routine accompaniment to the mealie rice. In fact, that simple meal has become so sought-after that one can find it on the menu of prime eating establishments like the Britannia Hotel in Durban. A coarser ground mealie grain called samp was an established part of Zulu cuisine. Indians spiced up samp with chilies and other condiments. Curried samp, nowadays frequently cooked with beans or meat, is a prized dish.

The grinding implements are also very similar to the Zulu and Indian methods. In Tamil, the “ammikal” is a flat granite stone that is accompanied by a rolling pin-type of stone. The “worral” is a standing receptacle in stone, wood, or metal, the contents of which are pounded by a pole-like tool. Variations of the same are found in any traditional Zulu household.

One dish that has the same name in both the Tamil and Zulu languages is ‘phutu’. Its pronunciation may vary slightly, but in terms of cooking method and taste, it is the same dish. It is commonly eaten with a soured milk called ‘amasi’ in Zulu, which is hardly different from the curd in Indian cooking. The curd has a cooling effect on the stomach, with the probiotics aiding digestion. The common ground in cooking traditions is potentially a fascinating area of inquiry that demonstrates that there is more that unites South Africans than divides them.

Selvan Naidoo

Image: File

Selvan Naidoo is the co-author of The Indian Africans together with Paul David, Kiru Naidoo, and Ranjith Choonilal.

Related Topics: