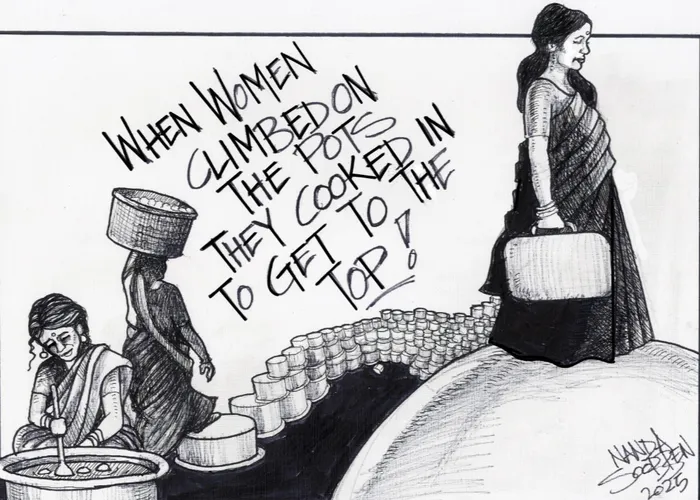

Honouring Indian women’s invisible labour in apartheid South Africa

Building economies

dfdfd

Image: Nanda Soobben

BEHIND every economic revolution lies a story the textbooks forgot. In South Africa, while apartheid carved visible scars through its legislations and violent removals, it also built invisible prisons, especially for women. Among the most underacknowledged survivors and strategists of this era were Indian women, who carved out informal economies not in boardrooms or factory floors, but in kitchens, sewing rooms, and prayer spaces.

These were not just homes. They were micro-enterprises. Schools. Sanctuaries. Sites of survival. These spaces were not just adapted, they were reclaimed. Lounges transformed into offices, dining tables into assembly lines, and courtyards into informal marketplaces. Every corner of the home became a canvas for ingenuity.

These were acts of transformation, where women turned scarcity into a strategic advantage. With minimal resources and maximum resilience, they blurred the lines between private and public, domestic and professional, creating hybrid spaces that sustained families and inspired communities.

When the apartheid government pushed Indian families to the peripheries through the Group Areas Act, they didn’t merely steal land; they disrupted livelihoods, dismembered communities, and erased dignity. But Indian women, many descended from indentured labourers brought to Natal in the late 1800s, didn’t vanish into helplessness. Instead, they quietly built something powerful: hidden economies grounded in care, skill, and resistance.

Let us be clear. These were not hobbies. These were not side hustles. Sewing saris, catering for weddings, tutoring children; these were not just acts of domestic kindness. They were sophisticated systems of economic survival and cultural resistance. But history rarely honours women who make roti instead of speeches, who organise savings circles instead of strikes. Yet, they too resisted.

And perhaps more enduringly so. In apartheid South Africa, employment opportunities for Indian women were not just scarce; they were systemically denied. The state and society often labelled them “dependents,” passive members of a male-led economy. Nothing could be further from the truth. With formal employment blocked by racism and patriarchy, women transformed their homes into entrepreneurial laboratories.

They built economies that worked not on contracts or profits, but on trust, reciprocity, and an ethic of collective care. Sari tailoring became a form of economic and cultural resistance. With each pleat sewn, women preserved heritage and taught daughters pride. Catering businesses sprouted in kitchens where biryani was not just food, but also a memory, a source of dignity, and a down payment on school fees or groceries. Informal tutoring emerged from a refusal to let children fail simply because they lived far from “better” schools.

Lounges turned into classrooms, and Indian women taught not only literacy but hope. And we must urgently redefine what leadership means. Leadership is not always visible. It is not always loud. Sometimes, leadership is the ability to hold a family together during displacement, to ensure a neighbour’s child eats when food is scarce, to stitch dignity into every hem. These are not exceptions; they are blueprints for a different kind of economy.

These women understood leadership differently, not as a status or title, but as the ability to uplift others through consistency, compassion, and a shared purpose. Take Aunty Fatima, who ran a secret classroom in her living room when schools shut down. Or Aunty Gita, who stitched uniforms by candlelight to feed her children and trained others to do the same. These women led without titles, inspired without applause, and survived without recognition. They were economists, teachers, psychologists, and leaders rolled into one.

Their leadership was not in commanding a crowd, but in sustaining one. Their labour was often dismissed as “helping out” or “making a bit of extra cash.”

But this rhetoric, casual and careless, contributed to a wider erasure. It justified why they never appeared in GDP calculations or employment statistics. Why did the government policy ignore them? Why did their children, even today, not fully grasp the complexity of their mothers’ enterprise?

But their stories live on, in oral histories, in recipes passed down, in stitched hems and balanced books. They live on in daughters who became accountants, professors, caterers, and seamstresses, professionalising what their mothers did with no formal recognition. They live on in the resilience we now applaud, forgetting the women who modelled it long before we coined the term. The truth is: economic history has long treated the informal as inferior. But informality is not failure. It is adaptation. It is resistance. And it is deeply gendered.

Feminist economists, such as Marilyn Waring, have long argued that what we call “the economy” is a fiction. This system counts what (mostly) men do in offices and factories but ignores what (mostly) women do in homes and communities. This fiction is why women like those in South Africa’s Indian communities were and remain left out of the economic archive. Their unpaid labour underwrote the very survival of generations.

Yet, in the eyes of the state, they never worked a day. But they did. Every day. And often into the night. This omission in economic records isn’t just about numbers; it’s about historical justice. When we exclude women’s unpaid labour, we erase the very engine that kept communities alive during apartheid’s cruellest decades. These women not only supported households, but they also shaped generational outcomes.

Their work laid the groundwork for the scaffolding upon which modern professional and academic success stories stand. Their erasure reflects not oversight, but a systemic refusal to value relational economies. They managed to make ends meet with what they had. They built networks of care when formal structures failed. They trained daughters not only in recipes but in resilience, not only in stitching but in self-worth.

They taught economics before the textbooks arrived. That is work. That is leadership. That is legacy.Today, as we grapple with what an inclusive, post-apartheid economy should look like, we must confront this omission. Not merely to honour the past, but to reimagine the future. South Africa’s development strategies cannot afford to overlook relational labour, care economies, and grassroots entrepreneurship.

And education systems must teach the history of women whose wisdom, grit, and enterprise have quietly, powerfully stitched the social fabric together. The narrative of Indian women in apartheid South Africa isn’t a footnote to resistance history; it is the missing chapter. It is time to write it in. Because they were never “helping out.” They were holding up their families, their homes, and their communities.

Dr Aradhana Ramnund-Mansingh

Image: Supplied

Dr Aradhana Ramnund-Mansingh: Manager School of Business MANCOSA, Empowerment Coach for Women, and former HR Executive

** The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of IOL or Independent Media.