Matric examinations: is it the window to the world?

Influence on career paths

Empirical evidence shows that students who perform well in matric are more likely to succeed at university, says the writer.

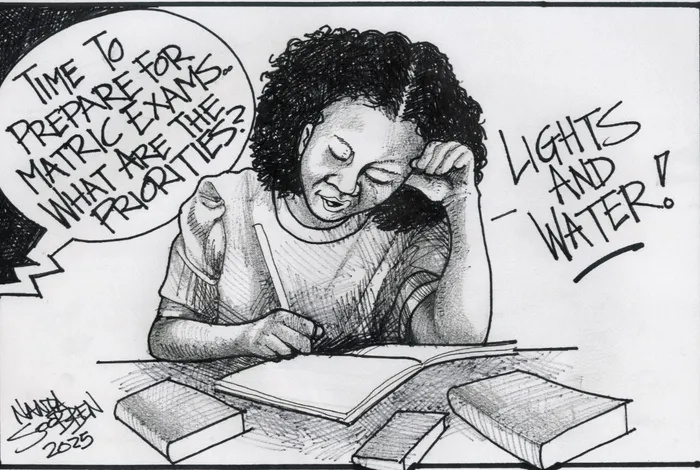

Image: Nanda Soobben

THOSE pupils who have been resilient enough - some in difficult educational environments - and have meandered through the previous 11 years of schooling, the matric examination is a just reward. This milestone in the pupil's academic journey creates anxious learners, teachers, and parents.

Matric marks the completion of secondary education and is often regarded as a gateway to tertiary education and future employment opportunities. However, the dream of obtaining a matric certificate is not a reliable indicator of tertiary acceptance and entrance into the job market. The matric examinations are intended to evaluate a pupil’s knowledge and competence across a range of subjects after 12 years of schooling.

Often, the intention is to assess the pupil's deep conceptual understanding of information pertaining to the different disciplines. The results obtained are used for various purposes: entrance to higher education institutions, qualification for bursaries/scholarships, and even consideration for direct employment. In many ways, these results function as a sorting mechanism, distinguishing those who are perceived to be academically capable of entering tertiary institutions from those who are not.

Matric performance often determines access to scarce opportunities in South Africa. For example, a high Bachelor’s pass opens doors to university degrees, which are generally linked to higher income levels and improved quality of life. Employers, too, often use matric results as a filtering tool when hiring entry-level workers. As such, the examination appears to play a pivotal role in shaping one’s prospects.

Empirical evidence shows that students who perform well in matric are more likely to succeed at university. Subjects such as mathematics, physical sciences, and English, in particular, correlate strongly with tertiary-level achievement. A strong matric performance also builds a foundation of discipline, perseverance, and study skills that are beneficial in future academic or professional settings.

Moreover, matric results can influence the kinds of career paths individuals pursue.

For instance, those who excel in mathematics and science may enter fields like engineering, medicine, or actuarial science - careers that are traditionally associated with higher earnings and social mobility. In this case, matric can serve as a launchpad for future success.

There are numerous stories of pupils who have lifted themselves out of poverty through hard work and perseverance. Great results provide hope. Great results offer better opportunities. These examinations are a simple stepping stone to a brighter future for many. But in South Africa we have a number of concerns.

Past inequalities have taken too long to be remediated. Unfortunately, the ruling government has shown less commitment to raising the educational standards for pupils to thrive in a Fourth Industrial Revolution environment. Pass rates have become a political football and not a goal to be attained through innovation and dedication. The pupil needs to become the focus.

Understanding of what is in the curriculum needs to gain greater momentum. Investment in better resources and more teachers may alleviate some of the problems.

School infrastructure and security need to be addressed urgently. These take time, but it should not take more than 30 years. Matric examinations are written under conditions that may not be equitable. Pupils in under-resourced schools, often located in rural or economically disadvantaged areas, frequently lack access to qualified teachers, learning materials, and proper facilities. As a result, their matric results may not reflect the pupils' true potential.

The playing field is not level, and poor matric performance may be more indicative of systemic inequality than individual capability. The high-pressure nature of the matric exam also raises concerns. Some pupils, despite being capable and hardworking, may underperform due to anxiety, personal circumstances, or health issues. Thus, a single set of exams taken over a few weeks cannot comprehensively capture a learner’s abilities or predict their future performance in all areas of life.

South Africa's post-school system offers various alternative pathways that do not depend solely on matric performance. Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) colleges, for example, provide opportunities for students who may not qualify for university but wish to pursue trades or technical careers. It is also odd that this type of training does not begin much earlier in the pupils' schooling careers. It is also important to acknowledge the broader structural factors that influence both matric performance and future success.

Inequality in education remains a persistent issue in South Africa. According to numerous studies, pupils from affluent backgrounds generally outperform those from low-income households due to better resources, parental support, and access to extra tuition. These systemic disparities mean that using matric results as a blanket measure of ability or potential can reinforce existing inequalities. A pupils from a township school who earns a 60% average may have achieved more - in relative terms - than a private school learner who earns 80%.

Currently, though, those pupils who attain higher marks in the disciplines that are sought after are likely to receive calls from higher educational institutions and funders. The sad reality that we face is that, often, the better performing pupils can afford university tuition themselves. Those who may need the bursaries and scholarships sometimes fall out of the acceptable range.

Indigent pupils have to work really hard to be eligible for such bursaries and scholarships. It can be done and I have seen such talented young men and women coming from the poorest of communities. It can be done.

Parents have great ambitions like their children. Everything will depend on what happens in those few weeks. The results will generally reflect the dedication shown by an entire group of people: the pupil, the teacher and the parent. But most of all, the true results depend on the investment made by the Department of Basic Education. To claim a particular pass rate is easy. To show that it was the true achievement will be much more difficult.

Vimolan Mudaly

Image: File

Vimolan Mudaly is a professor at the University of KwaZulu-Natal.

** The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of IOL or Independent Media.

Related Topics: