Unbowed and unbroken: the Story of Indian women in South Africa

Moral fortitude

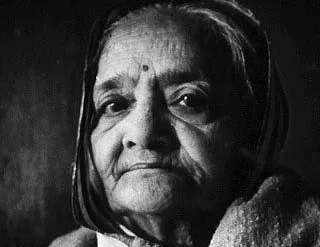

Kasturba Gandhi was a political being in her own right, resisting British laws in South Africa and later in India, says the writer.

Image: en/wikipedia.org/dinodia

INDIAN women historically and in contemporary South African society, embody a courage that is not momentary, but unwavering, and persistent. Courage that shows up loudly in the form of our most revered political activists, and also quietly, in everyday lives, lives that have experienced oppression, patriarchy, migration, forced removals, poverty, and ultimately survival.

The phrase "Unbowed and unbroken" has been widely used in academic scholarship to describe people who have faced incredible challenges yet continue to resist and persevere. This phrase aptly captures the resilience of Indian women in South Africa, who have embodied strength over the past 165 years while living in a country that, for too long, made them feel like outsiders.

Our ancestors, particularly the women who lived lives under servitude and indenture, a system akin to slavery, are often unacknowledged in the stories we hear of resistance and endurance. In truth, when writing the history of South Africa itself, Indian women are invisible, and their stories lie untold.

It has been argued that Indians were the only segment of Natal’s population who arrived through a “special and urgent invitation”. This invitation however was never intended for women to accept. Their inclusion in the system of indenture was as a result of the Indian government imposing regulations on the importation of indentured workers to the colony, which included a quota of 29% women, much to the disdain of the sugar barons and planters in the colony of Natal.

So from the very onset of indenture they were viewed as “dead stock”, deemed as having no value to the economy (Beall, 1990:58). In spite of this, they were nevertheless put to work under brutal conditions on sugar cane plantations, dairy farms, railways, coalmines or employed later on as ayahs (nannies) in white households. If paid at all, their wages were lower than the men, they were thought to not need as much food rations, and they were subjected to all forms of physical violence.

While faced with these multiple forms of marginalisation, by colonial authorities, and by patriarchy within their own communities, these women nevertheless, over the years, raised children, formed social networks to support each other, kept spiritual and cultural traditions alive, and resisted in the only ways they could, by surviving, and adapting.

My own family history is one example of this.

My grandparents engaged in subsistence fishing and market gardening, and I spent my early childhood years with a grandmother who remains, in my mind, a symbol of being unbowed and unbroken. She regularly travelled to India to procure goods such as clothing and jewellery to sell in South Africa.

Reflecting on this now, I recognise her entrepreneurial spirit as a bridge-builder between India and South Africa, facilitating the exchange of cultural commodities, which regretfully I did not recognise, or acknowledge as such while growing up. I have often wondered what made my grandmother brave. Brave enough to travel by plane, alone, in the early 1980s through various countries and across continents to go back and forth between India and South Africa.

You see, while she was multilingual, fluent in both Tamil and Telugu and could read and write in both these languages, she was unable to read and write in English.

To the oppressive regime at the time, she did not fit the mould of a business women or entrepreneur, or fit neatly into white South African society, yet despite what others thought of her, she not only defied the limiting beliefs that her own community may have held of her, but also the logic of what was considered elite, intelligent and superior at the time, forging a path and a future for herself and her family.

Looking back now, I see a tenacious entrepreneurial woman who pursued opportunities despite the circumstances she found herself in. She persistently chose the route of courage even when the alternative was comfort. I would argue that her relentless ability to adapt was a form of everyday resistance. She lived the courage that wasn’t always visible, but which held her family together.

The Oxford English dictionary defines courage as “the ability to do something that frightens one”, and “strength in the face of pain or grief.” Indian women throughout the years have displayed the moral fortitude to confront hardships rather than retreat in the face of it. Women like these provided the groundwork that allowed men in the political arena to flourish.

For example, Kasturba Gandhi (Mahatma Gandhis’s wife), was a political being in her own right, resisting British laws in South Africa and later in India. His mother Putlibai, laid the moral foundation of his life, teaching him that all life was sacred. The values and courage of these women became part of the very framework that guided Gandhi’s own journey.

In addition, it was the determination of Indian women that transformed the passive resistance campaign into a dynamic mass movement, recognised at the time as the largest general strike in South Africa. Moreover, during apartheid, Indian women generally were active in community-building, feeding activists, and forming civic organisations, even when their names never made headlines.

The resilience of Indian women in contemporary South African society is not always headline-worthy either, but it is equally as important. Whether living in historically Indian townships or newly integrated suburbs, women continue to navigate economic precarity, systemic racism, gender inequality, and family obligations. They are often still the ones who ensure that the household functions, that children are educated, and that cultural identity survives.

Even in post-apartheid South Africa, now five or six generations after the arrival of the first indentured labourers, many women are still trying to build a life that was denied to their mothers and grandmothers: a life of safety, opportunity, and dignity. It is thus important to remember that courage doesn’t only exist in the political arena. It resides in homes, in schools, in temples, churches, mosques and in communities where women persist, adapt, and build, often with no recognition, and little rest. We must honour not only the brave women with names in books, but the grandmothers, mothers and daughters who have stitched the fabric of our communities together.

Through acts of persistent courage, they not only survived, but flourished, unbowed and unbroken within a societal framework that sought to perpetuate their subordination, denigrate their customs, and marginalise their traditions.

If my great-great-grandmother, Chinnamma Guruvadu, who arrived in the colony of Natal in 1896, had dared to dream, could she have imagined that, generations later, her great-great-granddaughter would stand here, in a democratic South Africa, no longer enslaved but free, not merely surviving, but also holding the highest distinction our universities can bestow? Even in her wildest dreams, could she have imagined this moment?

The lesson here is that the sacrifices we make may not result in their intended outcomes during our own lifetimes. And while our sacrifices may not carry the same cruelty or brutality as those of the women who came before us, every small step we take, is a step toward ensuring that the women and children who come after us, can live a life beyond our wildest dreams.

Dr Kathryn Pillay

Image: Supplied

Dr Kathryn Pillay is a sociologist at the University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN). She is a National Research Foundation-rated researcher whose teaching, research, and publications focus on issues of race and identity. Pillay holds an honours degree in industrial psychology, a Master’s in industrial, organisational and labour studies, and a PhD in sociology from UKZN.

* She delivered the keynote address at the 150th anniversary celebrations of the Shree Emperumal Hindu Temple Society's Women's Day event on Sunday in Mount Edgecombe. The title of her speech was: “Unbowed and unbroken: the story of Indian women in South Africa". The theme was "The resilience of indentured women".

** The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of IOL or Independent Media.

Related Topics: