Navigating the challenges of higher education for South African matriculants

Tough choices

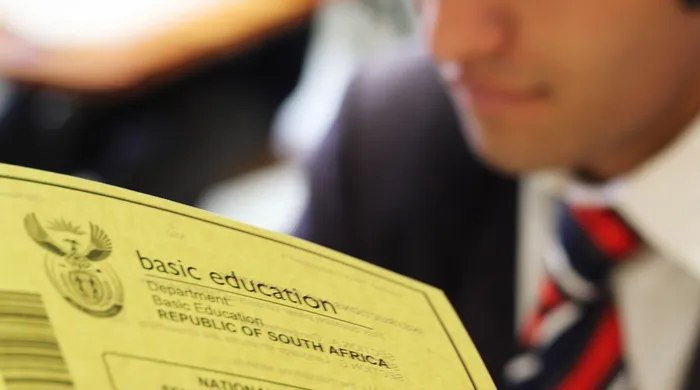

Access to tertiary education and quality employment remains deeply unequal, says the writer.

Image: ANA Archives

FOR matriculants, the choice of higher education and career pathways are more intimidating than any other challenge they will ever face. The landscape of tertiary education is undergoing rapid changes under the influence of globalisation, the digital revolution, and economic uncertainty.

Compounding the problem for these young children is the fact that the job market is becoming more competitive, with technology both creating new opportunities and displacing traditional roles. There are many challenges that matric pupils must consider as they transition to university or vocational education and prepare for entry into the labour market. Unfortunately, our challenges have been compounded by the intransigence of the governing party over the last 30 years.

Education should be a priority. It is not. Our children should be the priority. They are not. The future of our country should be a priority. Corruption is. So, there are some problems that matric pupils will experience as they negotiate the next few weeks. One of the most immediate challenges is the limited number of tertiary education places compared to the growing number of high school graduates.

There is no one-to-one relationship between the number of university spaces and the number of matriculants registered each year. Although this may be a global problem, South Africa’s demand far outpaces institutional capacity. Universities, unfortunately, often only prioritise merit-based selection, and in some instances, apply the quota system, leaving many qualified matriculants excluded due to resource constraints. Furthermore, the rising popularity of certain professional programs creates bottlenecks, intensifying competition.

Even when places are available and students are accepted, affordability poses a barrier. Tuition fees and living costs have risen faster than inflation. In many instances, students’ decisions about whether and where to pursue higher education are determined by affordability. The burden of student loans not only affects immediate access but also influences long-term financial security.

Matriculants must therefore weigh the trade-offs between investing in prestigious institutions and considering more affordable alternatives, including vocational training or alternative colleges. Employers increasingly report a mismatch between graduates’ skills and labour market needs. Many graduates are overqualified for the jobs they eventually secure, having greater theoretical knowledge. The rapid pace of technological change means that curricula often lags behind industry practical requirements.

Fields such as artificial intelligence, renewable energy, and data analytics are expanding, yet universities may not update programs quickly enough to keep pace. For matriculants, choosing fields of study aligned with future skills demands becomes crucial.

The Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) is reshaping the world of work. Whether we accept it or not, a large percentage of current jobs are at risk of automation. Routine, repetitive, and even intellectually inclined jobs, both manual and cognitive, are especially vulnerable. At the same time, new opportunities are emerging in areas such as machine learning, cybersecurity, and healthcare technology. The challenge for teachers and matriculants lies in preparing for jobs that may not yet exist, demanding a strong foundation in adaptability, problem-solving, and digital literacy.

Another factor reshaping education and work is globalisation. The internationalisation of higher education means that universities now compete globally for students, while graduates compete internationally for jobs. While this expands opportunities, it also intensifies competition. For matriculants in developing countries, studying abroad may seem attractive, but issues of recognition of qualifications and cultural adjustment present further hurdles.

Access to tertiary education and quality employment remains deeply unequal. Socio-economic background strongly influences university participation and success rates. Poor students and minority groups in South Africa may face additional barriers, from financial constraints to discrimination in acceptance at higher educational institutions and hiring practices at workplaces.

For matriculants, understanding these systemic inequalities is important in making realistic choices and seeking supportive environments. In choosing to join the medical faculty, for example, the quota system may apply, and a student has to perform really well.

Careers are no longer linear. The traditional notion of studying once, entering a profession, and remaining in it for life is being replaced by multiple career shifts. The future of work is characterised by great uncertainty, and constant work reinvention is necessary. When planning a career, think carefully about this. Matriculants must recognise that tertiary education is not an endpoint but the beginning of a process of ongoing skill acquisition.

A real concern is the psychological burden associated with both higher education and the job market. There are no guarantees of work after completion of degrees. This increases the rates of stress, anxiety, and depression among students. While the challenges are significant, matriculants must also be aware of alternative opportunities. Vocational education, online learning, and apprenticeships are gaining recognition as viable routes to employment.

Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) provides essential skills for rapidly changing labour markets. To respond to these challenges, matriculants should adopt proactive strategies. Conduct extensive career research. Explore sectors with future growth potential, such as green technologies, healthcare, and digital services. Ensure that the career choice is flexible. Choose study programs that allow cross-disciplinary learning and transferable skills. Ensure that there is thorough financial planning. Consider scholarships, bursaries, and more affordable institutions to avoid long-term debt.

You have to be resilient while at university. Build support networks among other students and faculty staff, and develop coping strategies for stress. Understand that learning is continuous. Complete as many short courses alongside your formal education as possible.The challenges awaiting matriculants in tertiary education and the job market are profound, shaped by structural inequalities, financial constraints, and technological disruptions.

Yet, they also open up new avenues for innovation, adaptability, and global engagement. To navigate this uncertain terrain, matriculants must balance ambition with pragmatism, equipping themselves with not only technical expertise but also resilience and flexibility. In doing so, they can transform challenges into opportunities and carve out meaningful pathways in the complex future of work.

Professor Vimolan Mudaly

Image: File

Professor Vimolan Mudaly is a professor at the University of KwaZulu–Natal.

** The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of IOL or Independent Media.

Related Topics: