The legacy of my Patti, Kanniamma Naidoo: a story of resilience and triumph

From indenture to independence

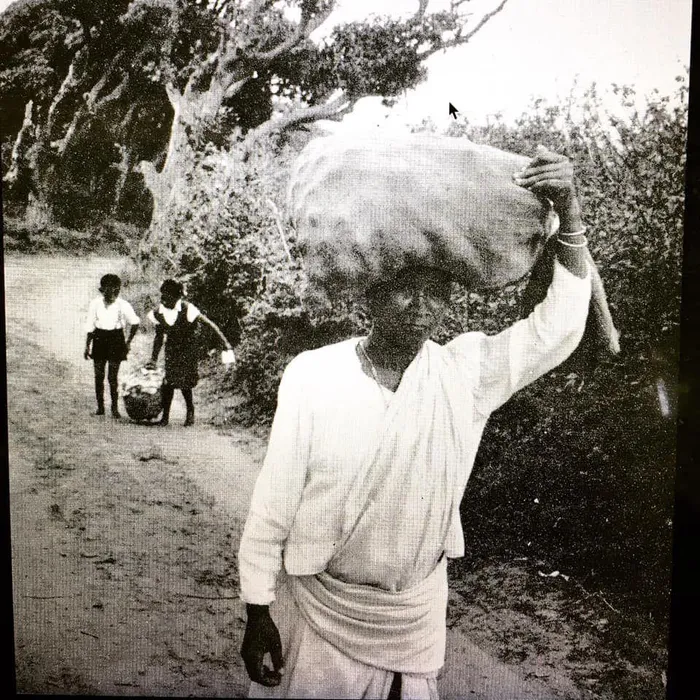

Kanniamma Naidoo, a petty vegetable street hawker.

Image: Selvan Naidoo Collection

MY BROWN eyes and 6ft tall physique, along with some of my melanin-deficient siblings and cousins, one being the offspring of a Gujarati and Tamil union, have dissuaded me from searching for my ancestry on my paternal side. Central to this side of the family was our matriarch, Kanniamma Naidoo, my Pāṭṭi (grandmother in Tamil).

Kanniamma, as I affectionately called her, was tall and sturdy with well-defined features. Her proud nose, embellished with a mookuthi (nose ring), exposed enlarged nostrils abused by years of snorting snuff that saw her live well past a century.

Kanniamma’s ancestral roots were discovered by accident when I made a trip to the KwaZulu-Natal Pietermaritzburg National Archive repository. I went in search of more information about my maternal ancestry that I was able to trace by sheer luck, in June this year, through the discovery of my maternal grandmother’s green identity card.

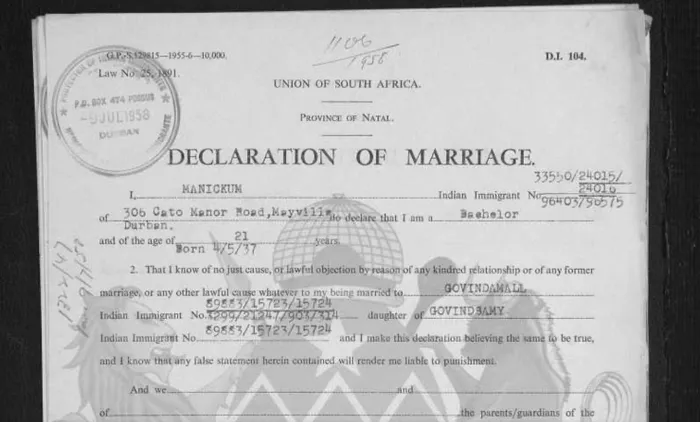

While at the repository, I found my parents' declaration of marriage certificate that located the indenture numbers of my maternal and paternal ancestry.

Petty street hawkers at The Squatters Market, Durban, 1910.

Image: 1860 Heritage Centre

On the marriage certificate of my parents, my paternal colonial-born grandfather was listed as the son of numbers 33550/ 24015, and 24016. Kanniamma, also colonial born, was the daughter of 26-year-old Kuppu Ramanjulu Reddy, number 96403, and 19-year-old Karpayamma Ersappa Gounden, number 96575.

Both Kuppu and Karpayamma arrived in Natal in December of 1902 aboard the Umzinto XXIX from Madras. They we both assigned to Sir Thomas Hyslop in Howick. The distance between the recording of their names on the ship’s list suggests that they were either married on or before the ship's journey to be assigned to the Hyslops. Kanniamma’s parents' journey stops here at the archives with further information about their lives that I hope to unearth with more time.

Kanniamma’s earlier life is not known to the family. We do know that she was young when she married Manikum, a waiter at the Edward Hotel in Durban. When Manikum, my grandfather, died at an early age, Patti took to vegetable hawking to feed her family. Her days were spent in the hustle and bustle of Durban’s streets, where she plied her trade as a petty vegetable hawker. She raised seven children and never complained about anything.

Early "Black Jacks" Municipal Police, Durban, 1900.

Image: 1860 Heritage Centre

She got by with little and was resourceful. Her panappai (moneybag), closely secured within the sari she wore every day was all she required to manage her budgetary responsibilities. Repressive street laws, colonial and apartheid control measures affecting petty hawkers, meticulously researched by Professor Goolam Vahed in a paper titled, Control and Repression: The Plight of Indian Hawkers and Flower Sellers in the Durban CBD, 1910-1948. ( https://disa.ukzn.ac.za/…/VahedGoolam3/VahedGoolam3.pdf) elaborates how people like Kanniamma were corralled into a peripheral economy that sought to deny them their livelihood.

Oral testimonies of my eldest brother and only living aunt bear further testimony to the numerous times that my Pāṭṭi’s goods were confiscated and never returned to her. Pāṭṭi was jailed on several occasions when she traded near the Umgeni Railway station. Her bail rescue from spending more time in jail was duly complied with by my dearest late aunt, Akka Ruby, who lived with Pāṭṭi in the famed Lorne Street (now Ismail Meer Street) of Durban.

During those days, when Pāṭṭi was jailed for not having her trading licence, she was often manhandled by "Black Jacks" (municipal police) with brutal force. The term "Black Jacks" later municipal police was used to describe poorly trained and often violent "policemen". The "Black Jack" police forces run by local administration boards and controlled by the local government patrolled the streets of Durban and were especially violent towards petty hawkers, in particular.

"Coolie Mary" as they were called in Colonial Natal were seen all over the streets of Durban, selling fresh produce, 1957.

Image: 1860 Heritage Centre

Despite this treatment and the repressive laws passed over several years to stifle a working-class existence, Kanniamma’s story is one of resistance, resilience, and triumph. She continued trading, often carrying her trusty bamboo baskets well into her eighties, and even after I had gone to university. My proudest memory of her was when she and my father stood alongside me when I graduated from university. It’s a moment that reminds me of the sacrifices that went before me in completely altering the trajectory of my future.

In a seminal paper titled Re-Conceptualising the “New System of Slavery” Academic scholar Richard Allen Heritage writes, failure to include the story of resistance, resilience, and triumph of Indenture “will serve ultimately only to diminish the meaning of the indentured experience not only for the three million men, women, and children who participated in these systems, but also for their tens of millions of descendants”.

Declaration of Marriage Certificate of the author's parents, indicating the indentured numbers on his maternal and paternal sides.

Image: Supplied

As we get closer to the 165th anniversary of the introduction of Indian indentured labour to South Africa in 1860, we must commemorate the heritage of resistance, resilience, and triumph of indenture through stories of people like Kanniamma Naidoo. We must celebrate their journeys of hard work and their commitment towards the pursuit of a better life for all our people.

Nandri Kanniamma, Mikka Nandri.

Selvan Naidoo

Image: File

Selvan Naidoo is the paternal great-grandson of Kuppu and Karpayamma and the proud grandson of Kanniamma Naidoo.

Related Topics: