The sari in South African history

A fabric of resistance

Frene Ginwala, then speaker of the National Assembly, flanked by Deputy President Thabo Mbeki, left, and President Nelson Mandela, 1996.

Image: Supplied

To write a history of 165 years is a daunting prospect. There are so many threads to follow, but at some point a garment needs to be stitched. Part of the challenge is to develop an overall narrative. In this quest, one of the strands that ran through the long 20th Century was the sari. As we scoured newspapers, read memoirs, and scanned photographs, the sari popped up in the oddest of places. In this adapted excerpt from our book Belonging: A History of Indian South Africans we drape some of those moments in history.

WHEN Sarojini Naidu - poet, nationalist leader and diplomat - arrived in South Africa in 1924, she was unlike anyone the country had seen before: a whirlwind in a sari.

By then, Indians were increasingly visible in the governance of British India, and were diplomats at Imperial Conferences and the League of Nations. Nationalists viewed overseas Indians "as dispersed fragments of a great Indian nation-in-the-making," each with their own role to play in the struggle for freedom.

Naidu brought this idea to life. Unlike the cautious Indian diplomat, she was instinctive, responding directly to the bullying of Indians in South Africa. As a poet, she turned injustice into words that stung, though like many poets, she had a romantic imagination and reached for solidarity. Decades before formal attempts at non-racial collaboration, Naidu envisioned a growing bond between Indians and Africans in South Africa.

Her impact was profound. At a moment when the optimism of the 1914 agreement had collapsed and harsh new anti-Indian legislation was spreading, Naidu embodied a rising assertiveness. Sari-clad, she spoke of taking on the Empire, while reducing racist white politicians to howls from the sidelines.

"How uncivilised," she would quip.

Mid-1960s: women donning saris in a tug-of-war contest.

Image: Supplied

In the Indian community, battered and bruised by constant attacks, she became an icon. Families named their daughters after her, photographs of her hung besides that of Gandhi in countless homes, and her presence lit a path for women like Zuleika Christopher, who later faced prison, banning, and exile for her activism.

In 1946 Dr Goonam was jailed for participation in the 1946 Passive Resistance Campaign. She described getting strip-searched by the wardress: I was … forcibly pushed into the room and thrust into a corner … The wardress proceeded to pull my sari off me. I was … stripped of every garment … She started digging in my ears and pulled off my glasses … I was then made to stand arms outstretched while she pulled my long hair vigorously till it hurt … I stood there completely naked in full view of the other prisoners.

Dr Goonam shares a light moment with Dr GH Mayat. Advocate IM Bawa is in the background.

Image: Supplied

And in 1952 there was the Defiance Campaign, a breakthrough moment in South African history as the Indian Congresses and the ANC joined forces.

As Jon Soske writes: The symbolism of Indians and Africans marching together proved crucial. In one of the most iconic images of the campaign, an Indian and an African activist (the one wearing a brilliantly white sari; the other sporting a trench coat, scarf, and heels) walked out of the female jail side by side, their right arms straight in salute, and their faces rapt with joy … The photograph conveyed unity through their simultaneous release (evoking the powerful motif of a passage from imprisonment to freedom), their womanhood and … shared excitement … African and Indian identities … found their common fulfilment in the integrating narrative of the struggle.

And at Kliptown, when the Freedom Charter was adopted, Indians "embodied the assembly’s – and therefore the nation’s – multiplicity. Contemporary observers waxed eloquent about 'young Indian wives with glistening saris and shawls embroidered in Congress colours (and) smooth Indian lawyers and businessmen, moving confidently through the crowd in well-cut suits'."

Decades after Naidu’s sari-clad inspirations, Frene Ginwala too began wearing a sari as a political statement under apartheid. When she joined the non-European queue in the post office, she was mistaken for a white protestor and thrown out. She went home, put on a sari and returned to the queue. Ever after, she wore a sari, even into parliament.

Pregs Govender, in her tribute to Ginwala in 2023 remarked: Today, I wear a sari, Frene, to honour you. You knew the power and danger of culture in a country in which a brutal apartheid state had co-opted culture to foster narrow, parochial ethnicities and nationalisms, racism, misogyny and xenophobia. Fascist leaders and states across the world continue to do this, pitting people against each other, instead of addressing the root causes of increasing inequality, poverty and violence. In 1994, you – a black woman of Indian descent in apartheid’s almost all-male, all-white Parliament, stepped into the most powerful position in the House, wearing a sari that reclaimed culture as celebratory and liberating.

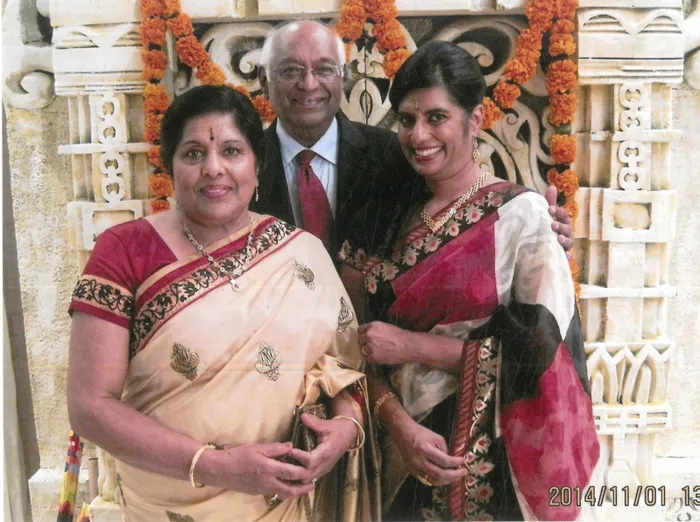

Vilashini Cooppan, right, with her parents, Ramachandiran and Sarojini.

Image: Supplied

More recently Vilashini Cooppan, whose grandfather Somasundaram Cooppan was the first student to matriculate from Sastri College and the first Indian to obtain a PhD, wrote how the sari signified the tying together of the threads of generations, linking them back to the streets of Durban: October 2014. Durban, South Africa ... I am dressed for one of the festivities in the week leading up to my cousin’s wedding. The sari I wear was bought by my father for my mother in 1976 …

But nearly forty years later it is I who tie the sari for the first time, the pleats falling with the luscious heft of fine old silk, its wearing a recompense for its long languishing. I remember the never-wornness of so many other saris, the ones my mother carried in her steel trousseau trunk from South Africa to Australia to Canada to the United States, the ones I would unfold and admire as a young girl in the afternoon quiet preceding a teatime without visitors, the ones that, in her diasporic loneliness, my mother slowly gave away. The day I wore that sari we had also gone, my parents and I, to a local sari shop where my father, a man who has breathed gifts his whole life, bought me three saris and my mother two, the doublings and repetitions falling thick on me as I remember.

The book's cover.

Image: Instagram

From Sarojini Naidu’s sari to the women of the 1946 Passive Resistance Campaign, from the iconic images of the Indian and African women walking out of jail side by side in 1952, to Frene Ginwala reclaiming the sari in apartheid’s parliament, the garment has endured as a symbol and a weapon. It folds protest and continuity, survival and celebration.

The sari has travelled across oceans and generations as a symbol of protest and of freedom. At a time where "civilisation" meant westernisation, it offered another meaning: belonging without assimilation, resistance woven into beauty. To wear a sari was to claim both history and future possibility.

Ashwin Desai

Image: File

Goolam Vahed

Image: File

Professor Ashwin Desai is at the University of Johannesburg and Professor Goolam Vahed is at the University of KwaZulu-Natal.

* Belonging: A History of Indian South Africans, published by Jonathan Ball Publishers, was launched at Ikes Books on Thursday.

Related Topics: