When the guardians are watched: the Madlanga Commission and SA's criminal justice crisis

Legal authority

The accounts provided by key witnesses weave a coherent yet deeply troubling narrative, says Professor Nirmala Gopal.

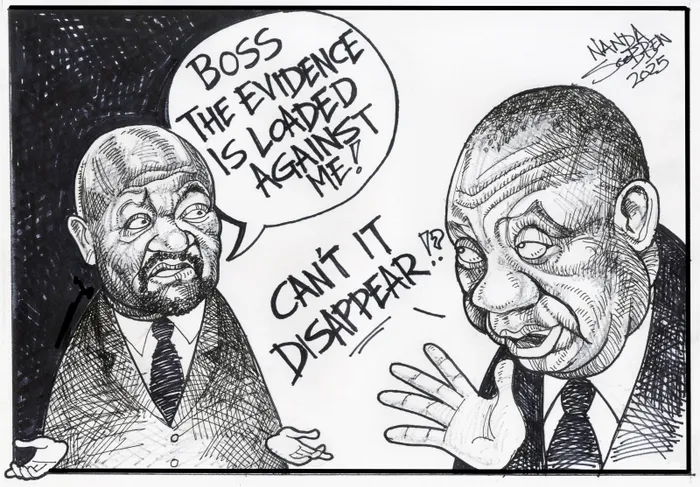

Image: Nanda Soobben

THE testimony emerging from the Madlanga Commission is revealing a much deeper crisis than just the 121 transferred dockets or a disbanded task team; it's foregrounding a pivotal question, namely: can South Africa's criminal justice system survive as a truly independent institution amidst systemic political interference and the erosion of accountability?

Recent proceedings have unearthed a chilling reality concerning how the mechanisms established to investigate political violence, historically critical in KwaZulu-Natal, might have been methodically dismantled from within structures that should oversee and uphold justice. Disturbingly, these actions were taken at the behest of political figures meant to ensure integrity in the policing system, not undermine it.

The accounts provided by key witnesses, including National Police Commissioner Fannie Masemola, and KwaZulu-Natal Provincial Commissioner Nhlanhla Mkhwanazi, weave a coherent yet deeply troubling narrative.

In March 2025, a dramatic incident unfolded when 121 active investigation dockets were abruptly transferred from the KZN Political Killings Task Team to Pretoria. This transfer occurred without any prior consultation with the provincial commissioner, leaving him in the dark about critical operational decisions that would profoundly impact the ongoing cases he was overseeing.

Recent allegations have emerged regarding Deputy National Commissioner Shadrack Sibiya, claiming he authorised a significant personnel transfer without legal authority. This decision has had serious consequences, leading to the abrupt disbandment of a task team that was actively engaged in building strong cases related to political assassinations. The manner in which this directive was communicated, a ministerial order demanding action "now, not even tomorrow”, has raised eyebrows due to its urgency. This rush appears to contradict established procedural standards. It has sparked concerns about the motivations behind the decision and its potential impact on the pursuit of justice in cases of political violence.

What we are witnessing is far more than a simple administrative reshuffling; it is a disturbing act of operational interference cloaked in the language of management reform. This development raises serious concerns about its implications for our justice system's integrity. When a minister issues directives that circumvent established command structures, it creates a toxic environment where sensitive case files mysteriously vanish into bureaucratic limbo.

Investigators, who have invested considerable time and effort into building intricate cases, are stripped of access to critical information and resources essential for their work. The response from the institution is not one of clarity or resolution, but rather a paralysing state of confusion that erodes the very foundations of legal oversight. This scenario impedes the effectiveness of ongoing investigations and sets a dangerous precedent, normalising practices that threaten the accountability and transparency crucial to the justice system.

As we navigate these developments, we must scrutinise the broader ramifications of such actions and advocate for restoring proper oversight and due process.

Commissioner Masemola’s testimony is particularly revealing, laced with contradictions. On one hand, he stated he would refuse to comply with unlawful instructions; on the other, he admitted to providing progress reports concerning the disbandment process. His rationale that he aimed to manage the disbandment "not in my approach, but in my approach" illustrates an official grappling with the tension between adhering to legal obligations versus yielding to political pressures. This dilemma neatly encapsulates how institutional capture occurs, not through overt coups, but via gradual erosions where officials convince themselves that their compromises are necessary for preservation.

The role of Parliament in this whole debacle, or rather, its conspicuous absence, is perhaps the most damning indictment of all. Mkhwanazi raised alarms with the Parliamentary Portfolio Committee on March 5, outlining his concerns regarding these developments. Yet, despite the warning signs reaching an oversight body specifically designed to act, the response was silence, leading to a deeper investigation into the hollowness of our oversight architecture.

We possess frameworks, protocols, constitutional powers, and an entire structure designed for accountability, but these mechanisms become ornamental when political will dissipates or partisan interests interfere. The Portfolio Committee on Police, equipped with the authority to summon officials, request documentation, or instigate investigations, performed none of these tasks effectively. Thus, the pertinent question isn't whether we have oversight systems in place but whether they are imbued with institutional courage, especially in critical moments.

The oral testimonies have established a foundational narrative as the commission transitions into a crucial phase. Still, the forthcoming documentary evidence will hold the power to confirm or dismantle these accounts. It is imperative to secure signed orders concerning those docket transfers and unveil ministerial directives, complete with timestamps and any legal assessments accompanying them. Additionally, diaries, emails, WhatsApp logs, and a thorough paper trail documenting who was privy to what information and when are essential to creating a full picture.

If such documents do not exist, it signals a grave reality where consequential decisions are made through off-the-cuff verbal communications and backdoor dealings, conspicuously avoiding any semblance of accountability. Conversely, if these documents do exist and corroborate witness allegations, we will unearth proof that senior officials knowingly overstepped their boundaries, actively disrupting critical investigations into political violence. The broader implications of these events extend far beyond the immediate context of KwaZulu-Natal or the tragic political killings, as devastating as they are for the affected families and communities.

The very testimonies presented highlight an overarching fragility within our criminal justice system; there exist contested chains of command within the South African Police Service (SAPS), a concerning degree of political interference in operational policing, and significant uncertainty among prosecutors and investigators regarding who ultimately governs their work. When institutions become susceptible to capture, whether by political actors, criminal networks, or an unholy combination of both, the rule of law transforms into a negotiable entity. In contrast, justice becomes conditional upon wielding power rather than adherence to process. As such, citizens are taught that outcomes are dictated by influence rather than procedural integrity.

Moving forward, the commission must secure direct testimony from Minister Senzo Mchunu, Deputy Commissioner Sibiya, and relevant officials from the Presidency who participated in discussions following Masemola’s escalation of concerns. These witnesses hold the potential to either exonerate or incriminate the prevailing narrative. However, the quest for individual accountability must be coupled with the urgent necessity for structural reforms. The Independent Police Investigative Directorate (IPID) is grappling with an extensive backlog, and the close ties between SAPS advisory functions and political offices cultivate profoundly dangerous vulnerabilities.

We need statutory firewalls that distinctly separate political oversight from operational command, ensuring that the criminal justice system remains an independent guardian of the law, fully capable of resisting the encroachments of politics and power. Only then can we hope to rebuild the integrity of justice in South Africa.do anything about it.

Professor Nirmala Gopal

Image: File

Professor Nirmala Gopal is an academic leader: School of Applied Human Science at the University of KwaZulu-Natal.

** The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of IOL or Independent Media.

Related Topics: