Betty Govinden (to the right of the tombstone) with her mother Devavarum Grace, brother Jonathan, aunt Purnaviniam, and cousin Crocus. The family was paying homage to Betty’s grandmother, Asseerwhadhum, who had arrived as an indentured migrant and worked on tea plantations.

Image: Betty Govinden

WHO better than the two intrepid travellers who charted the waters of indenture to steer us through and beyond the billowy seas of the Afterlives of Indenture?

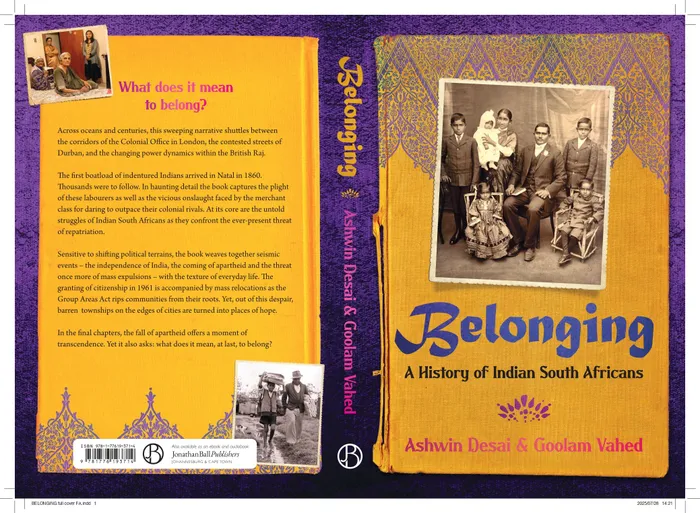

Ashwin Desai and Goolam Vahed’s new book, Belonging: A History of Indian South Africans, is an undulating journey through the highs, lows, and in-betweens of the histories of Indians in South Africa, since their arrival on these shores…

The impact of Ashwin and Goolam’s scholarship is to strategically move the margins to the centre. And if the centre is getting a little crowded, so be it. We have had enough of a lean, one-dimensional history in the old days, with Jan van Riebeeck at the centre.

From the varied, early lives of indenture and passenger Indians, we have a romp through the machinations of the colonial powers and the era of the agents-general from India, to the multiple and diverse roles that South African Indians themselves played in The Long Road to Freedom, across the decades of the 20th Century – all in a land where they were, for 100 years, seen as “permanent so journers”, as the threat of repatriation hung over, as the sword of Damocles…

Against the stereotyping of “Indianness” in South Africa, this book shows its infinite variety, with differences within differences, in a century of “seismic shifts” – from struggle, to survival, from conscientious settlement to unconscionable uprooting and relocation, from camaraderie to fissures and fractures in the body politic, from creating imaginary homelands, with curries, saris, music, drama and dance, to bold and unique fusion initiatives birthed on this very continent.

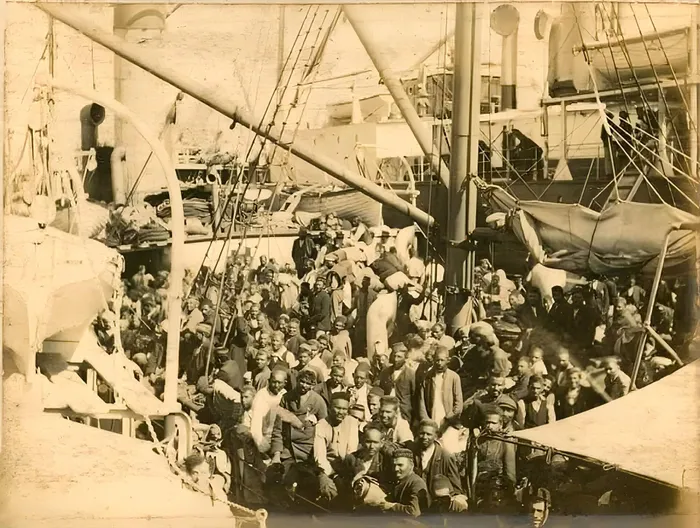

An early 1900s photograph of indentured migrants bound for Natal.

Image: Stewart Fairburn / SelvanNaidoo

Importantly, Belonging: A History of Indian South Africans charts the influence and impact of Gandhi on a century of South African political life. Indisputably, the early years of Satyagraha campaigns set the tone and pace for resistance to injustice. It was Fatima Meer, who consistently challenged boundaries of apartheid ideology, and stressed that we need to see Ahimsa and Satyagraha as being as indigenous to the political history of South Africa as Amandhla and Mayibuye Afrika.

In 1995, the year after our first democratic elections, Meer choreographed and produced Ahimsa and Ubuntu, a historical dance drama. Indeed, the early and mid-century Passive Resistance Campaigns were defining "threshold moments" alongside Sharpeville of 1960 and the Soweto Uprising in 1976, in our robust anti-apartheid history in South Africa.

The decade of the 1970s was also the time when one of our greatest freedom fighters and intellectuals - Steve Biko - who worked for “non-ethnic black solidarity”, was assassinated.

Belonging reminds us of how the Black Consciousness Movement worked for solidarity across oppressed groups, against the dark history of the late 1940s.

What Belonging does, strategically, is restore Indian women to our history. In her award-winning book, Coolie Woman – the Odyssey of Indenture, Gaiutra Bahadur, whose ancestry includes indenture to British Guyana, writes that the “stealing of the voices of indentured women - born into the wrong class, race and gender - to write themselves into history was structural… History had left these women voiceless…”

This is precisely what prompted my own exploration of Indian women and their writings, in my study Sister Outsiders – Representation of Identity and Difference in the Writings of South African Indian Women.

The book was recently launched at Ike's Bookshop on Florida Road.

Image: Supplied

Among the extraordinary women stalwarts, such as Dr Goonam, Fatima Meer, Phyllis Naidoo, Frene Ginwala, and Ela Gandhi, Belonging: A History of Indian South Africans also paints luminous portraits, among others, of defiance campaigner, Fatima Seedat, treason trialist, Ayesha Dawood, and Tyla Seethal, of recent Grammy Award fame.

We have the garlanding of our outstanding, internationally recognised academics and intellectuals, Uma Dhupelia-Mesthrie and Rajend Mesthrie, and of Vilashini Cooppan. “Commingling”, indeed!

The trope of Belonging: A History of Indian South Africans - born out of alienation and displacement, but also embodying grace and grail – emerges as a defining feature of Indian South Africans in this book.

Reflecting on the Indian women in my Sister Outsiders, I had observed earlier that I saw the women “writing back”, not to the ancestral homeland, India, but to the “beloved country”, South Africa: “They refused the longing for ancestral shores but carried their homes on their backs…

Belonging shows a people’s longing to belong. The poem that I composed in 2010, to mark the 150th anniversary of the arrival of indentured labourers to South Africa (November 16, 1860), celebrates the history of crossing the kala pani to another land, and the challenges of creating home and identity – of belonging. Part of it is reproduced below:

Tumbling from the great ghats in India

To the holding places in Port Natal,

Ushered in by the capricious tide;

Crossing the kala pani,

Children of the rain and storm,

Buffeted by waves; …

Tilling in coolie canefields,…

Preserving the ancient hearth,

With ladoos and rasgoolas -…

Lighting the family God-lamp,

With suppliant hands,…

Mingling blood and water

To forge a new people,…

The scripting and re-scripting of memory in multiple ways has marked the post-apartheid scene, since Mandela strode out of Robben Island, his head held high… Ngugi wa Thiongo, speaking at the Steve Biko Memorial Lecture in Cape Town, in 2003, stated: “… all memories have a place at the rendezvous of human victory".

Belonging shows us that we continue in A Time of Memory; and that “Memory and Truth are to be seen as two sides of the same coin”…

The book robustly deepens the work of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission as we, in South Africa, negotiate our different pasts in different ways, post 1994…

The book is an adamant “refusal of amnesia,” in the earnest project of “healing the wounds ofhistory”.

Belongingdemonstrates the persistence of memory... and as Don Mattera reminds us, “Memory is a weapon”… Whose memory? What does it mean to remember? How do we remember?

Yes, we remember through acts of memorialisation. We have anti-apartheid museums and monuments in honour of our heroes and heroines of the past. Our collective histories must be mirrored indifferent ways across the landscape of this land, as we depict the cartography of our struggle. But we must go beyond this.

Achille Mbembe, our foremost intellectual and thinker, has eloquently stated: “Honouring truth comes with the commitment to learn and remember together. As Edouard Glissant never ceased to reiterate, each of us needs the memory of the other. This is not a matter of charity or compassion. It is a condition of the survival of our world. If we want to share the world’s beauty, he would add, we remember together, and this doing, to repair together the world’s fabric and its visage.”

We must learn to remember together.

A History of Indian South Africans belongs to all who live in South Africa, and beyond…

Goolam, a historian, and Ashwin, a sociologist, have produced a wonderful book. To cover 165 years within the cover of a single volume would have taken a tremendous amount of sifting and distilling. The book is littered with many stories that provide a window into other stories. They have tilled the soil for more than two decades, and it is appropriate that they begin and end their book with Tagore: “The one who plants trees, knowing that he will never sit in their shade, has at least started to understand the meaning of life”.

As they write in their last lines: “For Indian South Africans, this speaks of their desire to belong, a desire that was grounded more deeply than any colonial plantation or racial nationalist ideology.”

Betty Govinden

Image: File

Dr Betty Govinden is an Honorary Research Associate, School of Social Sciences, UKZN

Related Topics: