“The light within”

Unveiling the cultural legacy of Indian indentured labour in Natal

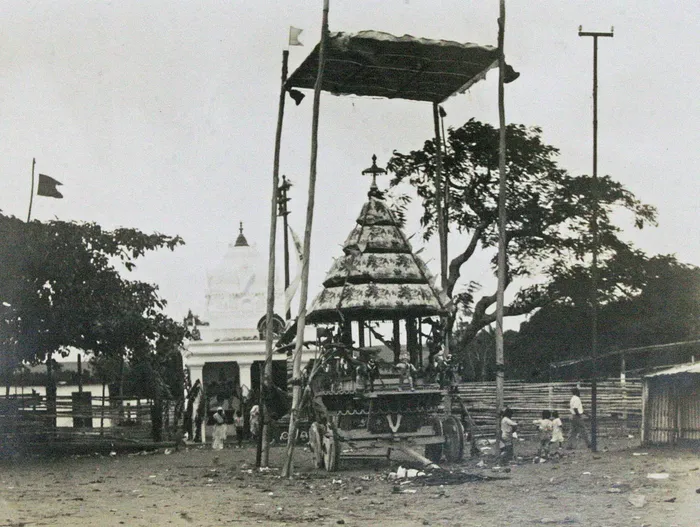

Ceremony in colonial Natal, 1889.

Image: Museum Africa

“We want temples wherein to worship. We should like the government to establish a Coolie location, and let us build a shrine there. They will nominate the holidays when the temple is built, as the law of the Colony allows. Whatever ceremonies are fixed, the free Coolies would celebrate the feast … and the assigned Coolies would take leave to attend for those three days (annual leave).”

The above testimony by Rangasammy to the “Coolie Commission” of 1872 reveals the desire of Indians to reconstruct their cultural and religious lives in Natal from the earliest days of settlement.

Over 80% of the indentured who arrived in Port Natal were Hindus. It is one of the fascinating aspects of history that the first official recognition of Diwali was in 1910, fifty years after the very first landing.

To the colonial white population in Natal, Hindu migrants were “heathens” and this very word was written under “Religion” on official documentation when one married. As the anthropologist John D Kelly wrote: “The colonial Europeans had little comprehension of, or patience for, the Indian religious tamasas, ritual festivals of indenture days. They saw heathen, ungodly, lewdness, dangerous tumult and disorder, and all the more evidence of the Indians bad character.”

For the authorities, the indentured were beasts of burden, cogs in a labouring machine. Witness the words of Katharine Saunders, the wife of a huge plantation owner.

An early photo of the Umbilo Temple.

Image: Supplied

She told the Wragg Commission of 1885, of which her husband was a member: "In regard to housing, sanitation and water supplies, I haven’t the slightest doubt that the Commission will report – forgive me – that the coolie prefers to live in a wretched grass hovel, and that sickness and the pollution of streams are due to his own insanitary turn of mind. This Colony already seems to believe that, because a person’s skin is a darker colour, he is less than human, and doesn’t require human conditions of living. Slavery is still so close behind us."

There were certain sugar barons who demanded that an indentured woman spend her wedding night with him. Overseers who brazenly raped women on the sugar cane field.

Witness the testimony of Sasamah: “I am the wife of Chengadoo of Rydal Vale Estate, Duffs Road. I am employed on the estate as field labourer. Three Mondays ago, the overseer asked me to lie with him. I refused. He asked me several times after this to lie with him. I declined to do so on all occasions. Last Monday afternoon, I was put to work alone, apart from other women, close to a cane field. I refused to work alone.

"He said that I must work where he says. I was doing my work. He left me and came back a few minutes after and said that he would have connection with me. With that he carried me into a large cane field. I cried out for help but there were no one working near to hear my cry. He carried me and threw me on my back in the field. He lifted up my cloth and got between my legs. Before committing the act, he stuffed cloth in my mouth and had connexion with me. I felt he passed semen into me. Before leaving me, he said if I told anyone he would cut my throat.”

Vellach complained to the Deputy Protector that Hulley, her employer, offered to pay her for sex while she was in his bedroom cleaning: “He came in, striking his pocket saying he would give me 3 if I would lie with him, as the mistress and her family had gone to town. I refused saying my husband would beat me. He said he would not tell him.”

Hulley’s defence was that he could not have made this proposition because Vellach was "unattractive". He was found not guilty. Sasamah’s case yielded similar results. The employer’s word was sacrosanct.

In this context of casual everyday brutality, the story of Rama and Sita became a potent source of inspiration. The indentured too saw themselves as exiled like Rama: "Bereft of goods, a mendicant, as slave, Rama to spend fourteen years in the woods."

In the Ramayana, Sita is portrayed as the faithful wife, Rama as the brave warrior and Ravana as evil. In Sita, the indentured men saw the model of a faithful wife, many of them having left their wives in India, or had partners who were constantly open to abuse, as the case of Sasamah illustrates. In the figure of the evil Ravana, they saw a “model of the delusions of powerful evil”, not unlike the overseers, Sirdars and employers they confronted daily. The play had a powerful resonance among the indentured population, as it showed that whatever the challenges faced, good would always overcome evil.

At a time when slave-like conditions gave people a feeling of what John Berger called “undefeated despair”, what more powerful a narrative to grip the imagination and give people hope than the story of Rama and Sita?

Historical records reveal that despite the warnings and violence meted out by the bosses, during their limited time off, the indentured used drama and music to keep their spirits going. Take the case of Durga, indentured number 84560, who worked for WB Turner of Howick. Durga told the Indian Protector in 1903 that around 7pm, he and “the other Indians were sitting in my house and passing our time by singing songs. My master came to the house and took the drum from me and chopped it to the ground. When it didn’t break he went and brought an axe and chopped it into four pieces”.

Turner admitted breaking the drum “because they would not stop playing and singing all night”.

But the indentured refused to stop dancing and singing, remembering traditions left behind. One is reminded of Rumi: “Don’t worry about saving those songs. And if one of our instruments breaks, it doesn’t matter. We have fallen into place where everything is music."

Despite the poverty wages and a system that historian Hugh Tinker described as a new form of slavery, the indentured built numerous temples in those initial years. Employees of the Durban Corporation, who were housed in the Railway and Magazine Barracks in the city centre, built three temples in the 1880s. Of these, the Durban Hindu Temple in Somtseu Road still exists, and continues to host the major celebration of Ram Navami.

C Behrens, who managed the estates of the Colonisation Company from 1867, told the Coolie Commission of 1872 that the “Coolies at Riet Valley have built a Hindoo temple, where they celebrate their own feast days. Those days are in addition to the holidays given to the Coolies by Law.”

Babu Talwantsing and Chundoo Sing, both of whom came as indentured workers, founded the Gopalall Hindu Temple in Verulam in 1888. One of the financiers of the Umgeni Road Temple, originally built in 1885, was a woman, Amrotham Pillay, who came as an indentured migrant.

Temples were a powerful source of comfort for many, as it was here that communal worship was experienced, birth, marriage and death ceremonies observed, and festivals celebrated. These were the very first incubators of community in an environment of incredible hostility.

The only time the indentured could leave the plantation was for three days to celebrate Muharram, what the whites called “coolie Christmas”. Despite being a Muslim celebration, indentured of all religions arrived in the city to celebrate. They took over the city and often fought pitched battles with each other. In 1891, the Superintendent of Police, Richard Alexander, reported: “On Sunday morning, during the Divine Service, the public were distracted by tom-tomming carried out in the Railway Compound. I went myself to stop it. I found about 1, 500 half-drunk coolies …I stopped the tom-tomming, but heard it again before I reached home.”

In 1908, divine intervention arrived in the struggle for some official recognition of Diwali. Swami Shankeranand arrived on these shores and immediately took up the struggle for Diwali to be officially recognised. Initially, the colonial authorities fobbed him off, mockingly inquiring, "how many coolie Christmases do you want to have?" But he persisted, sending letter after letter.

In January 1910, the education department declared Diwali a school holiday. Encouraged by this, in April 1910, Shankeranand organised a massive Ram Navami Festival. Participants met at the Umgeni Road Temple, and after the speeches, a crowd of approximately 4 000, accompanied by chariots, marched through the streets of Durban chanting “Shree Ramchandraji”.

When the procession returned to the temple, a feast was laid on and three wrestling bouts between North and South Indians, at which the African Chronicle newspaper reported “indentured Indian (South) was the best”. It was an impressive display and the white authorities took note, with the Durban Municipality granting employees a day off to celebrate Diwali.

And so it came to be that in 1910, Diwali took to the streets of Durban.

This Diwali, when you burst those fireworks and gorge on one more sweetmeat, ponder the words of Gandhi that was spoken on November 12, 1947. It would be his last Diwali: Only those who have Rama within can celebrate this victory. For, God alone can illumine our souls, and only that light is real light. The bhajan that was sung today emphasises the poet’s desire to see God. (“Light thy heart and sweep out from there evil thoughts and anger.”). Crowds of people go to see artificial illumination but what we need today is the light of love in our hearts. We must kindle the light of love within. Then only would we deserve congratulations.

Those words, spoken over 70 years ago, connecting the external festival of lights to a deeper, internal illumination, are more apt than ever.

Professor Ashwin Desai

Image: File

Professor Goolam Vahed

Image: File

Professor Ashwin Desai is at the University of Johannesburg and Professor Goolam Vahed is at the University of KwaZulu-Natal.

Related Topics: