Why Indian South Africans are no longer a “middle-man minority”

'Racial tag'

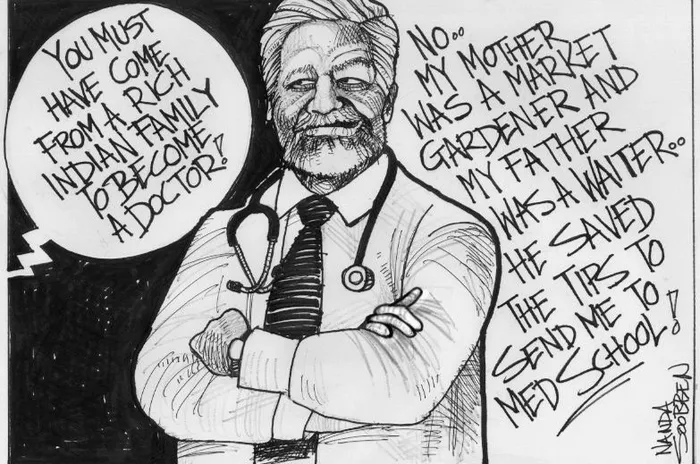

Research indicates that negative stereotypes of Indian South Africans persist in the post-apartheid era, and media reports sometimes fail to challenge racial profiling and stereotyping, particularly concerning economic or crime issues, reinforcing historical prejudices, says the writer.

Image: Nanda Soobben

THE term “Indian” defines a highly visible social group that is often perceived as homogeneous by outsiders.

Research indicates that negative stereotypes of Indian South Africans persist in the post-apartheid era, and media reports sometimes fail to challenge racial profiling and stereotyping, particularly concerning economic or crime issues, reinforcing historical prejudices.

Indian South Africans, in 2025, are no longer a sociological “middleman minority” created by Apartheid to serve as a physical, cultural, commercial and ideological buffer between Whites and Africans, but rather a profoundly diversified and structurally integrated component of the new South Africa.

The economic stratification, characterised by visibly high wealth on one side and significant unemployment on the other, demonstrates that the community has splintered along class lines, with material interests aligning with those of similar class segments across the national demographic.

This is now no different for all ‘race’ groups in South Africa.

The unemployment rate for Indian and Asian South Africans stood at 19.5% in 2021.

While significantly lower than the rate for Africans (38.2%) and Coloureds (28.5%), this rate is more than double that of White South Africans (8.6%).

This high unemployment figure directly contradicts the image of a stable, economically privileged “middleman” group.

The presence of a relatively high average income alongside a nearly 20% unemployment rate is the statistical signature of deep class division. The material interests of the unemployed and lower-skilled Indian working class are structurally identical to those of the working classes of all other groups.

Their struggles are defined by job access, housing, and social welfare, fundamentally divorcing them from the entrepreneurial interests of the high-income Indian cohort.

The primary causal factor in determining life outcomes, be it income, access to employment, health, or children’s schooling, is now demonstrably tied to an individual’s class position, superseding the historically imposed racial identity.

The political actions of Indian South Africans during the transition affirmed that their interests were already shifting from communal solidarity to class preservation.

In the first democratic elections in 1994, a striking observation was the non-alignment with the liberation movement: reportedly, over 60% of Indians voted for the former white minority parties.

This voting pattern was not a simple act of political opposition, but a reaction rooted in anxiety over the implications of majoritarian democracy, particularly the potential loss of relative status and increased competition for jobs and housing - issues directly relevant to their accumulated class advantage.

The decision to support opposition parties by significant parts of the professional class segment, despite historical anti-apartheid alliances, suggests that political ideology is now a market response to class defence, rather than ‘racial’ unity; notwithstanding the perceived failure of the governing party to combat crime, corruption, joblessness and obscene accumulation by unashamed, self-proclaimed billionaires in a system rigged in favour of the few.

External forces sustain the continued use of the “Indian” racial tag: the legal frameworks of racial redress that paradoxically constrain the professional class through employment quotas, and enduring social stereotyping that reinforces their status as a visible, homogeneous “other”.

For the majority of Indian South Africans, especially the working class struggling with joblessness, their core interests are defined by their class position, a struggle structurally indistinguishable from that of the broader working-class population.

Therefore, to achieve genuine deracialisation, policy implementation must increasingly decouple from rigid, historically imposed racial definitions and focus instead on socio-economic indicators to address inequality wherever it is found.

The democratic government, in its necessary quest for economic redress, continues to utilise the racial categories defined under Apartheid. This has, whilst benefiting a handful of tenderpreneurs (including politically connected Indians), resulted in a paradoxical legal status for Indian South Africans.

On the one hand, the Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment (B-BBEE) Act defines “Black” generically to include Africans, Coloureds, and Indians who are

South African citizens, thus theoretically providing Indian entrepreneurs and professionals access to ownership and capital benefits aimed at redressing historical disadvantage.

On the other hand, this inclusion is immediately complicated by the stringent application of the Employment Equity (EE) Act. The EE Act seeks to ensure employment demographics reflect the national or regional population profile.

This policy contradiction creates a structural barrier: the highly qualified Indian professional class, whose interests are rooted in meritocratic access to high-level jobs, faces legislative ceilings on employment and promotion based purely on their racial classification and geographical location.

They are simultaneously “Black enough” to qualify for ownership benefits under B-BBEE but “too Indian” to gain employment in certain regions or sectors under EE proportional quotas, notably in Durban, where they reside in significant numbers.

This legislative action ensures that the racial tag retains significant legal and material salience, overriding the objective class achievements and merit of individuals.

The community, however, remains heterogeneous in other ways apart from social class based on income, education and occupation. It is characterised by both imagined and real multiple origins (indentured or passenger), diverse linguistic group identifications, and varied religious beliefs. The linguistic shift further illustrates social integration and the decline of traditional ethnic silos.

Although various Indian languages (Tamil, Hindi, Telugu, Urdu, Gujarati, etc.) are still spoken, English has become the primary home language for almost all Indian South Africans. This linguistic assimilation facilitates greater integration into the broader urban professional and social sphere, a trend mirrored by the increased acceptance of ‘intermarriage’, particularly across similar class strata.

In summary, therefore, there exists an ongoing neoliberal capitalist normalisation of South African society. It is a situation in which material values are paramount for all groups, where wealth disparities are increasing, and where individual and class interests predominate.

However, in an era of right-wing identity politics, a regression into the racial laager mentality is unintentionally forced by the historical social DNA of Apartheid, especially when social anomie rears its ugly head as in Phoenix and other parts of the country in 2021.

Professor Dasarath Chetty

Image: File

Professor Chetty is a Visiting Professor in Malaysia, India and Germany and president of the International Sociological Association’s Research Committee on Participation, Organisational Democracy and Self-Management.