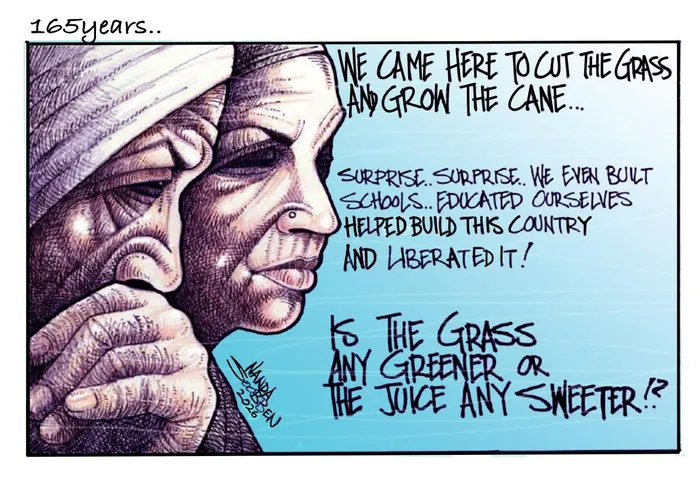

A cartoon by Nanda Soobben

Image: Nanda Soobben

THERE are some compelling studies on Indian indenture, tracing its origins to the British colonial era and the exploitation of cheap labour - often described as a form of human trafficking or "a new form of slavery" - from India to various parts of the British Empire.

Between 1834 and 1917, approximately 1.6 million indentured labourers were shipped to different parts of the empire, including Fiji, Trinidad, Suriname, Mauritius, Malaysia, Guyana and South Africa. Marxist historian, Hugh Tinker, noted several similarities between indenture and slavery: work incentives were centred on punishment rather than reward, and plantation labour was confined to guarded enclaves with authoritarian, oppressive command structures.

In 1839, the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society described the indenture system as “Slavery under a different name.”

The study of indenture has emerged over the past few decades as a specialised area of research in diaspora and migration studies, in contrast to its earlier relegation as a footnote in colonial history. Some of the leading scholars in the field are the progenies of indentured migrants, who are contributing to an understanding of “history from below”.

The late Fijian-born Professor Brij V Lal was one of the doyens in this field. Closer to home, we have innovative research by Professors Ashwin Desai and Goolam Vahed on the lived experiences of early migrants, “highlighting the multiple ways in which Indians tried to retain a measure of self-respect and autonomy in a system that sought to deny them the rudiments of bare life and dignity.”

This is not to deny the earlier pioneering work of Mabel Palmer, Bridglal Pachai, Surendra Bhana and Joy Brain, among others. The past decade has seen the field flourish due to the emergence of many family histories, the outstanding work of the 1860 Heritage Centre, and organisations like the 1860 Indentured Labourers Foundation in Verulam, whose contribution to the field is immense.

However, the groundbreaking work of scholars from the global South on the indentured diaspora is seldom acknowledged or cited by scholars in the global North - a case of Western academic hegemony?

The 165th anniversary of the arrival of indentured labourers in South Africa from India presents an opportunity for some critical reflections on this form of migration – including how they were recruited, the journey across the "kaala paani", their resilience and survival, and connections with India.

Terms such as kanganis, maistries, duffadars, arkatis, and sirdars are used to refer to recruiters and middlemen who lured illiterate villagers into exploitative indentured labour contracts, often through deception, coercion, misrepresentation, and fraud.

Gaiutra Bahadur has contended that those who recruited indentured labourers (for a commission) were portrayed in the “local imagination as schemers, liars, and even kidnappers. According to widespread belief, they did not inform. They misinformed. They gave recruits the false impression that they could return home from their jobs for the weekend: they promised work as easy as sifting sugar; and they exaggerated the gains to be had, inflating wages and conjuring lands of milk, honey and gold. In … folksongs, the recruiter is a cursed, vilified figure.”

As recorded in the Indian Immigrants Commission Report, Natal, (1887) simple, illiterate folk were lied to about the real purpose of indenture: “An Indian woman (who)… belonged to Lucknow, … met a man who told her that she would be able to get twenty-five rupees a month in a European family, by taking care of the baby of a lady who lived about 6 hours’ sea-journey from Calcutta; she went on board and, instead of taking her to the place proposed she was brought to Natal.”

The journey was long and arduous, taking between 10 and 20 weeks, depending on the destination, and about 17% died during the trip.

According to Lord Bhiku Parekh, three characteristics were specific to Hindu indentured labourers: the re-establishment of the family (after arriving as individuals), often in an oppressive, authoritarian, and patriarchal form; their religious faith, especially the acceptance of the Ramayana as the basic Hindu scripture; and the demise of caste.

The appeal of the Ramayana was related to the thematic connection between scripture and indenture: “Its central theme of exile, suffering, struggle and eventual return resonated with the experiences of the Hindu migrants, especially but not exclusively those of the indentured labourers. The Ramayana gave them conceptual tools to make sense of their predicament, articulated their fears, and showed them how to cope with these.”

Caste has almost disappeared in all the indentured zones. Since caste hierarchies are regional and not pan-Indian, they cannot be maintained in a population from diverse origins. Furthermore, all the migrants were packed in the same boat, eating the same food. Hence, during the journey, migrants became jehaji-bhai (shipmates), which created a new ‘kinship’ based on the shared memory of travelling on the same ship, regardless of caste or religion. The erosion of direct links with India also influenced the demise of caste.

A rhetorical question is the nature of connections with the motherland. According to activist Gopal Krishna, “(t)he story of the indentured labourers and coolies is the story of India’s open veins and arteries.”

Despite the distance and (dis)connection from India, the descendants of indentured labourers have maintained their cultural identity, and for this they have been criticised for being "separatist" and "exclusivist".

Professor Brij Lal succinctly captured the contradictions: “Indenture was a complex and contested experience, a site of both fragmentation and reconstitution, of liberation and disempowerment.”

Most descendants of indentured labourers have no direct links with India, except as an abstract, spiritual homeland. However, the indentured diaspora did have some influence on the liberation of India from the shackles of colonialism. After all, Mahatma Gandhi emerged from the indentured diaspora in South Africa, where he learnt and finetuned the art of peaceful passive resistance (satyagraha).

In the early 1990s, the Indian government sought to establish connections with the Indian diaspora to attract investments. In September 2000, the Indian government established a High-Level Committee on the Indian Diaspora to investigate and report on the "problems and difficulties, the hopes and expectations" of NRIs and PIOs in their interactions with India.

The High-Level Committee, chaired by Dr LM Singhvi, emphasised the importance of the Diaspora for India: The Diaspora is very special to India. Residing in distant lands, its members have succeeded spectacularly in their chosen professions by dint of their single-minded dedication and their hard work. What is more, they have retained their emotional, cultural and spiritual links with their country of origin. This strikes a reciprocal chord in the hearts of people of India.

Initially, there was little interest in the descendants of indentured labourers in countries such as Malaysia, Fiji, Trinidad, Suriname, and South Africa, who did not have dollars, pounds and euros to invest in India. An interesting issue from which the motherland could benefit was an acknowledgement by the High-Level Committee that in the indentured diaspora “a form of Hinduism… was being practised by people who had rid themselves of traditions and customs like jaati and sati, gotra and sutra …and dowry.”

Reflecting on the century since indentured labour was abolished, the Economist (2/09/2017) observed that “a shared post-colonial identity is now emerging, combining pride in India's economic rise, religious and cultural traditions - and, increasingly, commemoration of their ancestors' struggles to establish themselves.”

In 2025, the Indian government formally recognised the historical significance of its indentured diaspora through initiatives such as creating a database of all indentured migrants and their ancestral villages/cities and establishing research chairs and international conferences on the different facets of indenture.

In conclusion, the history of the Indian indentured diaspora reveals a complex legacy of exploitation, cultural resilience, and evolving identities. While rooted in a system often likened to slavery and human trafficking, the diaspora has also demonstrated remarkable adaptability and continuity of cultural traditions. Recognising these intertwined histories is essential for understanding contemporary debates around migration, post-colonial identity, and social justice.

As India and the global community reflect on this legacy, it becomes crucial to acknowledge both the anguish and the enduring spirit of those migrants who transformed their experiences into proud badges of resilience and cultural fortitude.

Professor Brij Maharaj

Image: Supplied

Brij Maharaj is a professor of geography at UKZN. He writes in his personal capacity.

** The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of IOL or Independent Media.

Related Topics: