Blood money: when insurance becomes a motive for murder in the Indian community

Chilling reality

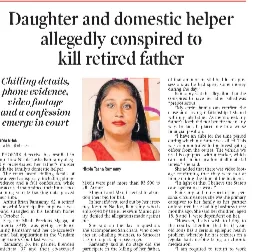

In last week's edition of the POST, we published a story about a Phoenix detective who testified in court how Nicola Tasha Ramsamy allegedly orchestrated her father’s murder with the family’s domestic helper. The motive is believed to be money-related.

Image: File

MURDER is the most universally reviled of crimes, the deliberate extinguishing of another human life. Yet, among the many motives that drive people to kill, few are as cold or unsettling as murder for financial gain. When a person takes the life of a spouse, parent, or relative to cash in on an insurance payout, the act goes beyond greed. It represents a collapse of morality so profound that it shocks even those accustomed to stories of crime and corruption.

In recent years, scattered reports and community whispers have exposed a troubling pattern: individuals within Indian communities in India and across the diaspora accused of killing loved ones for life insurance money. While not widespread, these cases provoke disproportionate outrage because they cut against the moral DNA of a community long associated with restraint, discipline, and family devotion.

They force a painful question: what could drive a person, raised in a culture that venerates family and condemns violence, to exchange blood for money? To understand the shock such cases evoke, one must recall the moral foundations of Indian society. For centuries, the principle of ahimsa nonviolence has shaped Indian spiritual and ethical life.

Rooted in Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism, ahimsa teaches that all life is sacred and that harm to another being carries deep karmic consequences. This ideal was not abstract; it was lived. Families taught their children to “control your anger,” “respect elders,” and “avoid conflict.” Violence was never seen as strength; it was seen as a loss of self control, a shameful surrender to base instincts. To harm another human being, especially a family member was to rupture the spiritual and emotional bonds that define existence.

This moral foundation persisted even through centuries of upheaval colonisation, migration, and modernisation. When Indians were transported as indentured labourers across the British Empire, they carried their values with them, building communities defined by restraint, respect, and familial solidarity. Colonial officials often interpreted this as docility, but in truth, it reflected a profound belief in the power of self-discipline and nonviolence.

Fast forward to the 21st century, and the landscape has shifted dramatically. The global Indian community is more diverse, mobile, and economically ambitious than ever before. Globalisation has expanded horizons but also exposed individuals to a relentless culture of competition and materialism. In many places, traditional moral frameworks have struggled to keep pace with the pressures of modern life. In this new environment, financial aspiration sometimes trumps moral restraint.

For some, the symbols of success the car, the home, the insurance policy become more than aspirations; they become obsessions. And when desperation, debt, or greed collide with easy access to life insurance, the unthinkable can happen. The psychology of murder for insurance is chillingly transactional. The victim is no longer a loved one, but a line item a policy value. The act itself is not born of rage, but of calculation.

In this sense, it is perhaps the most alien form of murder within Indian culture: it lacks passion, revenge, or emotional explosion. It is violence stripped of humanity, morality, and even pretence pure, methodical betrayal. To reduce these crimes merely to greed would be simplistic. Many of the individuals who resort to such horrific acts do so under enormous economic strain. They may be buried in debt, out of work, or trapped in social systems where failure is stigmatised.

In both India and its diaspora, economic status is often tied to family honor. The pressure to “succeed” to send money home, to maintain appearances, to keep up with peers can be suffocating. For some, especially those already emotionally fragile or morally adrift, these pressures warp their sense of right and wrong. An insurance policy, meant to protect families in times of loss, becomes a perverse lifeline. The logic turns inward: the policy is worth more than the person. And once that thought takes root, it festers. The act of murder becomes rationalised as a solution rather than a sin.

When such crimes occur within the Indian community, the reaction is visceral. Beyond the legal ramifications, there is deep social stigma. Families of perpetrators are ostracised, their names whispered in shame. Murder, especially within the family, is not only a crime it is a desecration of izzat (honor), a stain that can linger for generations. This communal disapproval has long served as an informal moral safeguard. Fear of social disgrace often deters wrongdoing more effectively than fear of prison. Yet, in increasingly individualistic and fragmented societies, this moral pressure weakens.

As people become more isolated emotionally and geographically the collective conscience that once restrained behaviour loses its hold. The rise of digital anonymity, the normalisation of quick money, and the erosion of communal support systems all play a role. The Indian moral tradition, once rooted in accountability to family and community, now competes with a global culture that prizes success over sacrifice and independence over interdependence.

When insurance motivated murders occur, the legal system responds harshly as it should. Perpetrators are charged not only with murder but often with fraud, conspiracy, and deception. Civil law ensures they cannot benefit from their crime: a killer cannot inherit from their victim, nor collect the policy. But as with all reactive systems, justice comes too late. The victim is already gone, and the moral failure has already unfolded. Law can deter, but it cannot mend the moral fabric once it’s torn. It cannot rebuild the sense of empathy or moral awareness that might have stopped the act in the first place.

The deeper challenge, then, lies not in punishing such crimes but in preventing them. This requires a reengagement with moral education not in a religious sense, but in a human one. It means teaching people that life cannot be measured in monetary terms, that desperation must never override decency, and that family bonds are sacred, not transactional. Behind every act of murder for money lies a crisis of meaning. It signals a society that has begun to equate human worth with financial value.

In communities where status and security are increasingly linked to wealth, the temptation to see life itself as an asset can quietly take hold. This is not merely an Indian problem; it is a global one. But within the Indian context where ahimsa and familial duty have long been defining virtues such acts reveal a painful cultural dissonance. The individual who kills for an insurance payout is not only breaking the law; they are renouncing an entire moral heritage that teaches reverence for life and family.

In many ways, this moral crisis reflects a broader struggle: the tension between tradition and modernity, between collective ethics and personal ambition. As materialism rises, spirituality and morality risk becoming peripheral. The old internal compass that once pointed clearly toward right and wrong now flickers uncertainly in a fog of social and economic anxiety. So how can the community reclaim its moral footing? The answer is neither to idealize the past nor to demonise modernity, but to reconcile the two.

Education systems, religious institutions, and community organisations must work together to reintroduce conversations about ethics, compassion, and empathy. These cannot be treated as outdated values but as essential life skills in an era of moral ambiguity. Families, too, play a crucial role. Moral guidance cannot stop at career advice and academic achievement it must also include lessons on humanity, humility, and the sanctity of life. Equally important is addressing the structural pressures that drive desperation.

Debt relief programs, mental health services, and community support networks can help prevent economic and emotional breakdowns that might otherwise spiral into tragedy. The antidote to moral collapse is not punishment but prevention not fear, but understanding. Murder for insurance money is more than a crime of greed; it is a moral tragedy. It reflects a society that has lost sight of what truly matters that human life cannot be quantified, that trust cannot be monetised.

For the Indian community, which has built its reputation on discipline, integrity, and compassion, such acts are particularly painful. They remind us that moral inheritance is not selfsustaining. It must be nurtured, taught, and lived every day. At its heart, this issue forces us to ask: what is the true cost of our modern ambitions? When the pursuit of financial security becomes so consuming that one could take a life for it, we must confront not only individual guilt but collective responsibility. Because in the end, no insurance payout can restore what has been lost not just a life, but a moral compass.

Professor Nirmala Gopal

Image: File

Professor Nirmala Gopal is an academic leader: School of Applied Human Science at the University of KwaZulu-Natal.

** The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of IOL or Independent Media.