Commemorating 165 years of indenture to South Africa: challenging Thala Vidhi in search of a better life

Indelible legacy

Women working gangs in Mount Edgecombe, 1939.

Image: 1860 Heritage Centre

MY FATHER was from a generation that showed little emotion toward their children. Hugs and kisses were rare, if not entirely nonexistent. For him, there was no time for emotion. His dharma was to simply provide a better life for his family; this was all that mattered to him. It was only twice that he showed affection towards me. On both occasions, he kissed my forehead. The first was when I got my matric certificate, and the next was when I became the first in my family to graduate with a degree from the University of Durban-Westville.

It was only years after his death, I realised why a man who showed so little emotion kissed my forehead on both those occasions. He understood what those moments meant for him and his family. For the first time in 136 years, since his ancestors arrived as indentured workers, we were able to alter the trajectory of being trapped in a cycle of the working class. Like my father and the many generations that came before, working as sugar cane labourers, municipal workers, waiters, factory workers, railway workers, and petty market garden hawkers was all we knew.

For them, their Thala Vidhi, a Tamil phrase that describes the invisible inscription of life’s destiny (vidhi) written on their forehead (thala), was to be challenged. What was written on their foreheads changed when they left the port cities of Madras and Calcutta. Every forehead of the 152 184 indentured workers who came on 384 ships from the villages of Bihar to Visakapatnam to Vellore had challenged and rewritten their Thala Vidhi. Their fate changed when they crossed the kaala pani, arriving at the African homes to build the country their descendants call home.

In this African home, is it possible to determine the degree of the contribution of the Indian indentured population to the colony of Natal? To what extent were they able to rewrite their Thala Vidhi and that of their employers? In a chapter titled The Coming of the Indians in a book by EH Brookes and C.de B Webb, the full impact of indentured labour notes that “towards the close of the 1860s, sugar production in Natal amounted to approximately 8 000 tons. When indentured labour was finally stopped in 1911, it was 82 000 tons.”

Flower Sellers in central Durban plying their trade, 1906.

Image: 1860 Heritage Centre

By 1959, that amount stood at a staggering 1.128.187 tons, well after indentured workers started leaving the plantations from the 1890s. It is safe to say that the sugar industry of the 20th century had its Thala Vidhi entirely rewritten, with the introduction of indentured workers that first arrived 165 years ago on November 16, 1860.

Beyond the economic contribution, indentured Indians rewrote a political Thala Vidhi with mass mobilisation of the great strike of 1913, when Indian indentured workers on the Natal plantations and mines brought to the fore the "ordinary" heroes and heroines who risked life and limb for a larger, collective cause.

The 1913 workers’ strike in South Africa was a major protest against discriminatory laws, particularly the £3 annual tax on ex-indentured Indians. It involved over 50 000 workers in Natal and the Transvaal who struck in mines, plantations, and other industries. The power of the indentured masses as they came out to fight against the untold oppression experienced in the mines, plantations, hotels, and railways significantly altered the Thala Vidhi of South Africa’s political future.

That milestone in worker resistance was recognised by the distinguished president of the African National Congress, Oliver Tambo. On accepting Nelson Mandela’s Jawaharlal Nehru Award for International Understanding in New Delhi on November 14, 1980, Tambo said: “It is fitting that on this day, I should recall the long and glorious struggle of those South Africans who came to our shores from India 120 years ago. Within … years of entering the bondage of indentured labour, Indian workers staged their first strike against the working conditions in Natal. This was probably the first general strike in South African history. Their descendants, working and fighting for the future of their country, South Africa, have retained the tradition of militant struggle and are today an integral part of the mass-based liberation movement in South Africa.”

Women workers on a sugar cane plantation in Esperanza, South Coast of colonial Natal, 1903.

Image: 1860 Heritage Centre

Thirty-three years later, a new thala vidhi was written by the 1946 passive resistance campaigners, launched by the Natal Indian Congress. This passive resistance campaign became a vehicle of protest against the Asiatic Land Tenure and Indian Representation Act, which excluded Asiatics from occupation of controlled areas in and around Durban.

By 1936, only 20% of Indians owned houses in Durban that were made of brick, stone, or concrete; the rest lived in wood and iron structures. These workers are remembered each year on the 13th June, 1946, which was declared as Hartal day when 20 Indians began the passive resistance campaign on a Thursday night by pitching 5 tents on vacant land in a controlled area at the junction of Gale Street and Umbilo Road and camping there.

This group of 20 men, under the command of Dr GM Naicker, chairman of the Natal Indian Congress, kept the strictest discipline.

Dr Naicker remarked: “If and when he and his men were arrested or removed from their camp, another 20 would move in to take their places.”

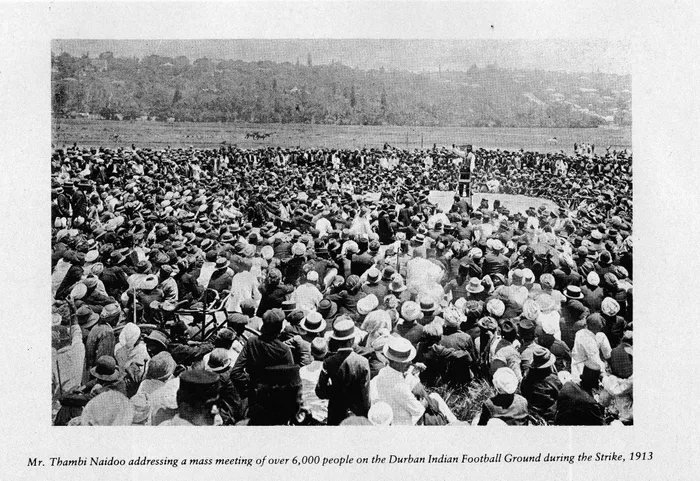

Thambi Naidoo addressing a mass meeting of over 6 000 people on the Durban Indian Football Ground during the Strike, 1913.

Image: 1860 Heritage Centre

Decades later, descendants of Indian indentured labour were firmly entrenched in the armed struggle for a non-racial, democratic South Africa. Indian Africans in South Africa have played a very positive and constructive role in the historic struggles against apartheid racial oppression. Former president Thabo Mbeki addressed a meeting of the KwaZulu-Natal Tamil Federation at the Chatsworth Stadium in Durban on April 10, 2003.

In the context of the national elections, a few days away, being held on the day of the Tamil New Year, he reminded everyone of the role of Indians in our country: “The elections are four days away, and one of the things I would like to see is that the Indian population of our country should go out on that New Year’s Day to vote. The Indian population of our country must exercise the democratic right for which many Indians fought, for which many Indians made many sacrifices, to ensure that we get the right to vote, and I am talking about important leaders of our people, not only leaders of the Indian people, but leaders of the people of South Africa.

"I am talking about people like Monty Naicker, like George Ponnen, MP Naicker, like Billy Nair, Kay Moonsamy, and Lenny Naidoo; all of these are great heroes among our people who fought.

"Lenny died so that all of us should be freed, and to honour them, let us, on New Year’s Day, our New Year’s Day, the Tamil New Year’s Day, let us all go out and vote. That is also important because the Indian population of South Africa has a duty and a responsibility to play an important role in determining the future of South Africa.”

Monty Naicker addressed factory workers at Volksrust during the 1946 passive resistance campaign.

Image: 1860 Heritage Centre

In determining the future of South Africa, 165 years since the first indentured workers arrived in Natal on November 16, let us draw on the inspiration of our indentured ancestry and their descendants to rewrite the Thala Vidhi that is inscribed on our foreheads. A vidhi where, in the words of Ravigasen Pillay, “we claim our space” in the land of our birth, placing marigolds for our ancestors who toiled for our tomorrow.

Kaiyile Agasam, Kondu Vandha Un Pasam Kalame Ponalum Vazhnthidum Rasa Kannile Neerada, Kanja Nelam Porada Poothadhe Ayiram Poo Sirichidu Rasa.

Your love brought the skies within our grasp!

This will live on, even when time is gone!

As tears filled our eyes, as scorched fields put up a fight.

A thousand flowers now in sight!

Time to smile, son!

Selvan Naidoo

Image: File

Selvan Naidoo is the great-grandson of Camachee, indentured number 3287, and Director of the 1860 Heritage Centre.

Related Topics: