From indenture to the property moguls

Cruel forced removals

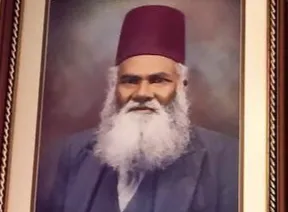

ML Sultan, also known as Mulukmahomed Lappa Sultan, born in Kerala State, managed to rise above the shackles of servitude, said the writer.

Image: Supplied

IN 1860, the first group of indentured Indian labourers, a total of 342 souls, arrived in Durban aboard the SS Truro to toil as indentured labourers in the sugar cane plantations. Until 1911, over 150 000 Indians were brought to Natal bound by five-year contracts; they endured harsh conditions on sugar estates.

After completing their terms, many chose to stay, transitioning into free labourers, market gardeners, and small-scale traders. The descendants of these indentured labourers continued to pursue various business interests within the confines of colonialism and later apartheid. Land ownership has been of seminal importance to the indentured community and their descendants.

Initially, it was agricultural land that was sought, a result of having worked on the land for so many years, and later residential property as a home. The entrepreneurial spirit prompted rapid expansion in the real estate sector, with several families prospering from the 1950s to the early 1990s. However, the post-apartheid era witnessed the largest success in the property market, marked by the rise of property moguls.

After indenture, many turned to tenant farming, vegetable farming and informal trade, laying the groundwork for future business ventures. The work of ladies sewing and cooking, as well as selling snacks, helped prop up the household income. Early Indian business hubs, such as Grey Street, became a commercial epicentre, with Indian merchants dominating the textile, fruit, and spice trades. Remaining in the colony of Natal was a challenge, and the British tried various means to induce the “Girmitiya” to return to indenture, applying a £3 tax penalty on those who remained in the colony after the end of their indentured term.

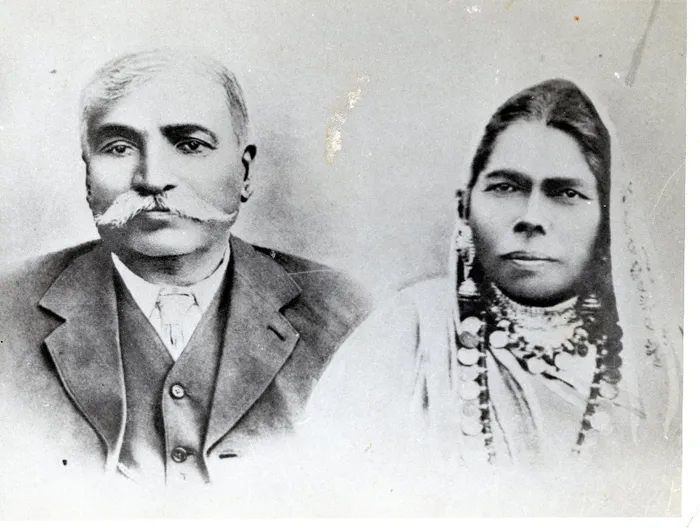

Babu and Mrs Bodasing.

Image: Supplied

Many were forced to choose between returning to indenture or returning to India. ML Sultan, also known as Mulukmahomed Lappa Sultan, born in Kerala State, managed to rise above the shackles of servitude. He started as a “coolie” porter, and his success in business saw him investing in property and establishing a soft goods business, known as ML Sultan and Sons at 106 Victoria Street in Durban

The evolution of property entrepreneurs cannot be understood without appreciating the dense networks of kinship, trust, and cultural capital that surround them. This enabled risk-sharing, collective savings, and informal mentoring. Religious institutions, mosques, temples, and community halls became sites of social organisation and business incubation. The stokvel and lottery systems of rotational savings schemes were integral in capital mobilisation for initial property purchases.

The low wages earned by them confirmed that the accumulation of initial capital was a slow and arduous process, supplemented by income from market gardening and hawking, where every penny was carefully managed, with a strong emphasis on thrift and collective saving within families. The concept of the "family business" took root early, where all members, including children, contributed labour and resources.

This collective effort was essential for survival and for generating the small surpluses needed for investment. For instance, a family might save for years to purchase a small plot of land, a cart, or a stock of goods for resale. Some families were able to accumulate wealth at a much faster pace than others. The Bodasing family had an early start. They built a sugar farming empire on the North Coast of Kwa-Zulu-Natal.

Babu Bodasing was the first to set up a plantation in 1866 It was not until World War I in 1915 that interest in cane growing began to be of economic interest among Indians. By 1930, approximately 500 Indian farmers were engaged in commercial cane cultivation. This presented a competition with white farmers, and calls were made for the regulation of the sugar-producing industry.

The segregation of Indian people started during the Victorian era under British colonial rule, they concentrated their entrepreneurial skills in particular geographical areas. It was during this period that the young barrister MK Gandhi arrived in the Natal colony, his efforts forever changing the course of the emerging Indian business community, later influencing South African liberation leaders. Before Group areas, The Broome Commission was appointed in 1941 to investigate the "Indian" problem with much emphasis on segregation.

Many petitions were made by Indian businessmen, including an attempt to apply the corporate veil, alleging that a company has a separate legal personality from its shareholders and thus cannot have colour. In Dadoo Ltd v Krugersdorp Municipal Council, the case centred on the application of separate geographical areas reserved for property ownership by Asians. Dadoo Ltd., a private company, acquired property in Krugersdorp that was designated for "Europeans" under the Act. The court ultimately ruled in favour of the Krugerdorp Council, upholding the notion of reserved areas with an intent to restrict land ownership based on racial classification. This case was in an era before the introduction of apartheid and the Group Areas laws.

Under the apartheid regime, the Indian community in South Africa faced a legal and bureaucratic system deliberately designed to curtail their economic progress and entrepreneurial expansion. The Group Areas Act was the cornerstone of apartheid spatial planning. It forcibly designated residential and business areas for specific racial groups. The cruel forced removals from areas that were declared "white" areas, relocation of families and businesses to less desirable, under-serviced townships on the urban periphery.

This destruction of commercial nodes dismantled thriving, centrally located Indian business districts. The relocation meant losing their properties, customer base, supply chains, and the economic synergy of a concentrated commercial centre. Restrictive Trading Licenses and provincial ordinances gave authorities wide discretion to deny trading licences to Indians, particularly in areas designated for white ownership. This created a system that blocked expansion.

The combined effect of these laws was to "cage" Indian entrepreneurship, preventing its natural growth and confining it to specific, state-controlled geographic and economic zones. This systemic discrimination aimed to secure economic privilege for the white minority. Many challenged these restrictions, including Danny Chetty, one of the first estate agents of colour, who wished to buy commercial real estate in the “White” commercial area in the late 1970s, he enlisted the help of Advocate Ismail Mahomed (later the first Chief Justice of South Africa), Chetty was one of the first to successfully circumvent the apartheid laws and went on to own commercial property in a "white" part of town.

From Corner Shop to Hotelier, the Thumba Naidoo family carved a path that reflects the transition from a small, family-run general dealer. The corner shop provided a critical foundation, generating steady cash flow, teaching business management, and allowing for the accumulation of savings. This capital was then reinvested to purchase or establish hotels, including the famous Butterworth Hotel in central Durban and many others, representing a major diversification and scaling of the family business.

Bertie Naidoo and LM Naidoo, a family that became a recognised name in the hospitality sector, purchased the landmark Himalaya Hotel in the early 1970s. This success was built upon similar foundations of thrift, family labour, and strategic reinvestment of profits from earlier ventures, such as Berto Bodies, which built the bus bodies.

Durban's urban geography, shaped by segregationist planning and economic zoning, ironically created niches for Indian property investors. Areas like Grey Street, Brickfield Road, and the Warwick Triangle became epicentres of Indian commercial activity. During the late apartheid period and especially after 1994, entrepreneurial families expanded into suburban and metropolitan property development. Some third- and fourth-generation descendants emerged as “moguls” with multi-million-rand holdings, often managed through family-run property management companies. Real estate became both a symbol of success and a vehicle for intergenerational wealth transfer.

The transition into the property sector was facilitated by several post-apartheid developments: The abolition of racially discriminatory property laws in the early 1990s, the emergence of Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) legislation and the availability of commercial finance through community-linked banks. However, Indian entrepreneurs often operated outside the formal BEE procurement value chain, relying instead on familial investment and direct acquisition strategies.

This created an alternative mode of accumulation that did not always align with state-led empowerment models, but proved effective nonetheless. Property moghuls such as Saantha Naidu, Ashok Sewnarain and Vivian Reddy are among the names that dominate the real estate landscape in Durban today. They employ a large number of people and have built property portfolios exceeding several hundred million.

This journey from exploited labourers to real estate moguls encapsulates a broader narrative of resistance, adaptation, and aspiration, and as South Africa seeks more inclusive models of development, the Indian property entrepreneur’s legacy offers valuable lessons in resilience, communalism, and innovation.

Advocate Lavan Gopaul

Image: File

Advocate Lavan Gopaul is the director of Merchant Afrika.

** The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of IOL or Independent Media.

Related Topics: