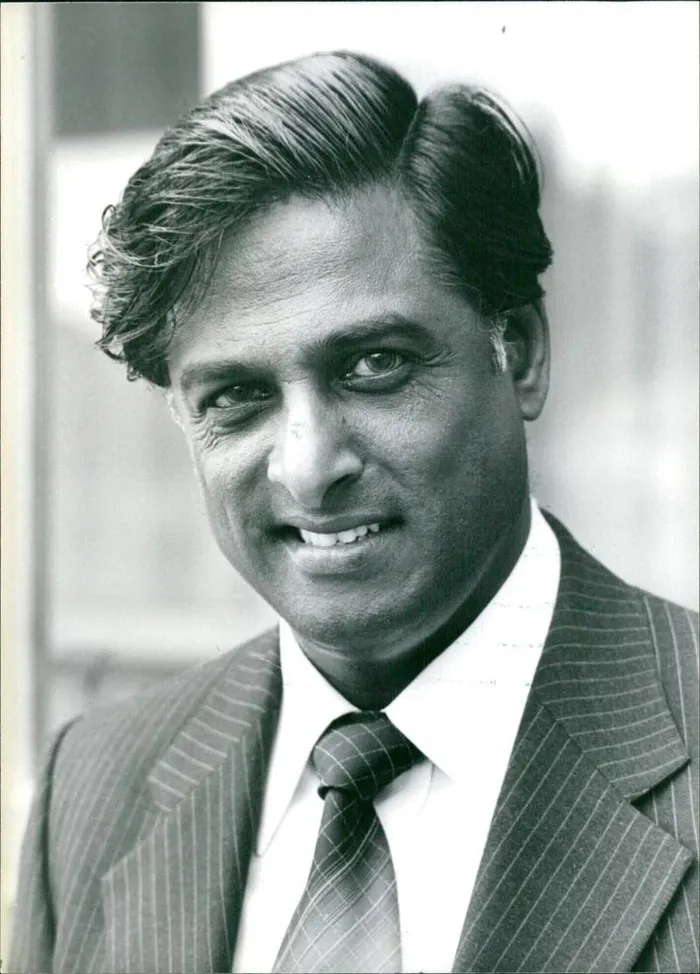

Palanisamy “PI” Devan

Image: File

On the occasion of the 165th anniversary of the arrival of the first indentured labourers to then Natal from India, it is propitious that the history of Chatsworth – the first developed municipal township for Indians - is traced. In Glimpses of Rural Chatsworth, a collection of writings of the land, the people, their occupation and generally their way of life in Chatsworth prior to the development of the Chatsworth Township, the late community leaders Palanisamy “PI” Devan and Jayaram “JN” Reddy contributed a detailed account.

Devan wrote:

After completing their contract of indenture in the Province of Natal, some pioneer Indians had taken occupation of land in Chatsworth at the start of the last century. They cleared the bushes and put the virgin land to the cultivation of vegetables and fruit. Their commendable labour which brought unprecedented success to the production of sugar cane in Natal was also conspicuous in their agricultural produce in Chatsworth.

By the middle of the 20th century, Chatsworth was not only the largest producer of bananas in the country but also supplied a variety of other fruit and vegetables to the Durban market. Although their contribution had enhanced the economy of the province, the Indian farming community had not received any encouragement whatsoever from the government of the day.

In 1960, the peaceful agricultural community of Chatsworth was uprooted from their lands, home and hearth to make room for a mass housing scheme. The only livelihood of a vibrant and progressive community was shattered by the Durban City Council to enable it to implement the despicable Group Areas Act of 1956. In this context the sad fate suffered by the people, mainly Indians, in well-settled localities such as Clairwood, Cato Manor, Mayville, Seaview, Queensburgh and Riverside (Durban North) cannot be ignored.

JN Reddy

Image: File

Reddy wrote:

No story of Chatsworth would be complete if consideration is not given to the developments which contributed to the demise of a flourishing farming community of some 15 000 people. Despite the fact that Land Bank funds and Agricultural Technical Services of the Department of Agriculture were denied to Indian farmers, they faced difficulties and overcame challenges and succeeded in the face of adversity. However, sinister forces were at work, secretly planning to deprive the Chatsworth farmers of their land.

When the news first leaked out it seemed too far-fetched to become a reality. In 1939, the Anti-Indian agitation against Indian encroachment into working class white areas, more especially in the City of Durban, gave rise to the emergence of white politicians whose election manifestos in the main comprised measures to restrict the economic and social mobility of the Indian community, who through self-help and sacrifice were registering progress albeit gradually.

The United Party politicians in all three tiers of Government in Natal thrived on promoting the need to enact legislation to curtail the progress of the Indian, as they saw the Indian as a competitor at the workplace, in the professions and in trade and industry. In 1939 Parliament passed the Pegging Act to control the sale of white-owned property to Indians. The Pegging Act was followed by the Asiatic Land Tenure and Indian Representation Act in 1946, which legislation contained even more restrictive measures, including the need for building societies to apply for permits to grant building loans to Indian applicants.

The white politicians went even further and successfully exerted pressure on the building societies in which Indians invested their savings to refrain from lending money for the building of homes. This move was designed to bring to a halt Indian housing development pending the outcome of the secret plans which were being hatched to move Indians from the urban areas and their resettlement in areas across the Umhlatuzana River in the south and the Umgeni River in the north, while ensuring that the white suburbs located between the two rivers in question would not be disturbed.

The planning and layout of a township across the Umhlatuzana River for sale to Indians became a reality in 1947. The motivation for the approval of Umhlatuzana Township by the authorities was based on the fact that the township developer, Carl T Schelin, had stated categorically on the township plan presented to the Township Board for approval, that the creation of the township was in keeping with plans envisaged by white politicians, for the resettlement of Indians on the basis referred to above. The defeat of the United Party of General Jan Smuts in the Parliamentary elections of 1948 dealt a severe blow to the United Party politicians belonging to all three tiers of the government in Natal, who were confident that the United Party would again be victorious.

Had this been the case, the leader of the United Party in Natal, Douglas Mitchell, whose anti-Indian stance was well-known, would have been identified to head the Ministry of the Interior and thereby be in a position to legislate and give expression to the often-expressed desire of white politicians to make life impossible for Indians. The National/Afrikaner party coalition which succeeded the United Party in parliament in 1948 had a slender majority and consequently had to tread warily. The government of the day was fully aware of the plans which had been mooted by the United Party in Durban to deal with the so-called Indian problem, arising from the serious concerns expressed by whites, following upon the purchase by Indians of homes in the working- class white suburbs in Durban.

Therefore, the promulgation of the Group Areas Act by the National Party Government was no doubt designed, among other things, to win the support of a solid block of white voters in Natal. This legislation would allow politicians in Natal to legally implement far-reaching discriminatory measures and ensure its effective implementation by the local authorities and the Provincial Government controlled by the United Party and to satisfy their long-cherished desire to resolve the so-called Indian problem to their satisfaction.

Following the passing of the Group Areas Act, two planning reports were presented for consideration by the Durban City Council. The one planning report was prepared by the Provincial Regional Planning Commission and the other by officials of the Municipality of Durban. The planning reports dealt with the identification of land for the resettlement of the Indian community in terms of the provisions of the Group Areas Act. Both the plans to a very large extent were compatible and, more importantly, there was agreement on the relocation of Indians across the Umhlatuzana and Umgeni Rivers.

When the Group Areas Act became operative, Indians were restricted from acquiring or developing properties without a permit. During this period Natal was under the control of the United Party. The Indians were virtually fenced in and could not develop the properties they owned in the urban areas despite having to pay rates annually to the local authority. The identification of and purchase of land across the Umgeni River intended for low-cost housing was not possible, because the land in question was in the main owned by whites who could not be forced to part with sugar cane-producing land on which a major industry was dependent.

The above consideration, coupled with the fact that such a move would antagonise the sugar millers and embarrass both the Government and the United Party in Natal, resulted in the decision to first develop land across the Umhlatuzana River, on which approach there was consensus between all three tiers of government. The land identified for housing development across the Umhlatuzana River comprised vast tracts of farming land which provided a livelihood for some 15 000 Indians and 2000 Africans.

The farmers were engaged in cultivating tropical fruit and vegetables, including the internationally recognised Cavendish Dwarf bananas. The loss of farming land in Chatsworth, and in the absence of any plan by the authorities to provide suitable alternate land for the rehabilitation of the displaced farmers, was in fact the beginning of a process which progressively reduced the extent of farming activity carried on by the Indian community in Natal. The responsibility for the acquisition of land identified for housing in Chatsworth was entrusted to the Durban City Council whose councillors had campaigned over the years, both overtly and covertly, for the removal of Indians from the city and adjoining white areas and their resettlement across the Umhlatuzana and Umgeni Rivers.

The Central Government had without much effort identified a willing partner prepared to accept the challenge of acquiring the land in question and to plan and lay out a massive housing scheme including the infrastructure necessary to promote such an undertaking. The funding was underwritten by the central Government. The Durban City Council’s involvement was not an act of charity. It was a calculated exercise from which the City Council benefited financially, while at the same time satisfying a long-cherished desire of white politicians, one of whom, Jim Higginson, was involved in the development of Chatsworth and additionally had a major highway serving Chatsworth named after him.

The resettlement of Indians in Chatsworth achieved two purposes. Firstly it satisfied the designs of the white politicians to remove Indians from the urban areas of Durban and adjacent boroughs, and additionally, by displacing Indian farmers without providing them with suitable alternative farming land, effectively put them out of business. Immediately thereafter emerged a large number of whites who within a very short space of time became very profitable banana farmers, cultivating land on the North and South Coasts of Natal.

These white farmers had access to funding from the Land Bank and technical support from the Department of Agriculture. In addition a Banana Board was established to safeguard the interest of the emergent white farmer and, in the process, put an end to banana farming by Indians outside the Chatsworth area. It is, therefore, obvious that the fate that befell the Indian banana farmer was not by accident, but rather by design in order to transfer banana farming to whites, free from any competition from the hardy Indian farmers.

Many of these farmers who lost their farms and holdings settled in the townships which were being developed by the private sector in the larger Chatsworth complex and others were allocated homes in the housing scheme undertaken by the municipality of Durban. All the Indian families who were forcefully moved to the Chatsworth housing scheme faced many challenges and the fact that hawkers supplied milk, bread and groceries for a considerable period in the absence of shopping facilities bears testimony to the difficulties and problems they had to contend with.

The street lighting was pathetic, there were no doctors’ surgeries, clinics or any medical facilities, and in the absence of telephone services the going was indeed tough to say the least. However, from within the ranks of the people settled in Chatsworth, there emerged men and women who to the best of their ability through representations to the authorities at various levels ensured that the necessary amenities and services were provided as speedily as possible to satisfy the needs of residents of Chatsworth.

The teaching fraternity of Chatsworth, in whose care were placed children from various parts of the larger Durban area, also faced an enormous challenge, but with commitment and dedication they imparted education of a high quality as part of their contribution towards the forward mobility of children, some of whom came from areas where educational facilities were inadequate, thereby adversely affecting children from low income families. The saga faced by Chatsworth farmers was a tragedy perpetuated on a voiceless people by whites, who saw Indians as a serious threat to their future well-being both economically and socially.

Notwithstanding the hopelessness of the situation, the farmers fell back on a proud tradition and legacy handed down by our forebears and rallied the support of the community to overcome the challenge they faced and to start life anew. It is fitting to record that from within the ranks of the families settled in Chatsworth have emerged medical practitioners, including medical specialists in a variety of fields, attorneys, advocates, judges, engineers and artisans involved in a variety of fields including telephone technicians. The opening up of employment opportunities for Indians completing studies at technikons and universities presented serious problems because of the attitude of white trade unions and surprisingly white professional bodies whose members saw the Indian as a competitor and a threat to the monopolies which they had thus far so jealously guarded.

It was my privilege to have been afforded the opportunity to head negotiations with employers and professional bodies on the basis that having regard to the serious skilled manpower shortage in the country, it was manifestly unfair to deny suitably qualified Indians the opportunity to supplement the skilled workforce and resolve the impasse in which commerce, industry and the country at large found itself. It was on the basis of these arguments that a new era of opportunity and progress for Indian graduates from the technikons and universities was opened up and the colour bar which hitherto had prevented Indians from entering most professions and skilled trades was lifted.

This development also provided opportunities for other disadvantaged people of South Africa.The successful outcome of these negotiations brought relief to various sectors of commerce and industry as evidenced by the fact that among other companies, Indians were employed by Eskom, Telkom, Iscor, Sasol at Secunda and Vencor at Newcastle. Nearer home the Natal Society of Accountants were prevailed upon to lift their restrictions and grant articles to Indian clerks who wished to qualify as chartered accountants. I have no doubt that many of our youth took advantage of these and other opportunities that arose following upon the breakthrough. The community is also deeply indebted to the late Dr Alec Solomon, Rector of the M L Sultan Technikon, for his assistance in the provision of specialised technical training as requested by certain of the major companies referred to above.

Yogin Devan

Image: File

Yogin Devan is a media consultant and social commentator. Reach him on: [email protected]

** The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of IOL or Independent Media.

Related Topics: