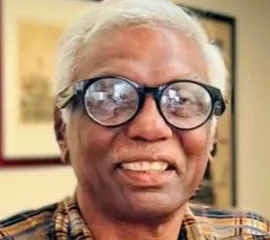

Solly Mapaila, General Secretary of the South African Communist Party (SACP). His party's decision to contest local elections separately from the ANC marks a historic shift in the Tripartite Alliance, says the writer.

Image: Facebook/SACP

SOUTH Africa’s festive calm has been punctured by a development that carries profound implications for the country’s political future. The South African Communist Party (SACP), a central pillar of the historic Tripartite Alliance alongside the African National Congress (ANC) and the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU), has confirmed its intention to contest upcoming local government elections independently.

This marks a decisive departure from a tradition that has endured for decades: the SACP influencing governance through alliance rather than electoral competition. The timing of this decision is not incidental. It comes in the aftermath of the May 29, 2024, national elections, which produced South Africa’s most significant political realignment since 1994. For the first time, the ANC fell below 50% nationally, securing approximately 40% of the vote and losing its parliamentary majority.

The result compelled the formation of a Government of National Unity (GNU), bringing together parties with sharply divergent ideological traditions, including the Democratic Alliance (DA) and the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP). It is against this backdrop that the SACP’s independent electoral path must be understood.

The SACP’s role in South Africa’s liberation struggle is historically indisputable. For much of the 20th century, the ANC and SACP operated in close ideological and organisational proximity, sharing leadership, strategy, and sacrifice. Figures such as Chris Hani, Moses Mabhida, Joe Slovo, and Ruth First embodied a fusion of nationalist and socialist traditions that shaped the liberation movement’s character.

The 1955 Freedom Charter, long regarded as the ANC’s foundational policy document, bore unmistakable social democratic and socialist influences. After 1994, the alliance transitioned from resistance to governance. SACP leaders and intellectuals occupied influential positions in Parliament, Cabinet, and the state, including portfolios central to industrial policy, trade, and higher education. The Tripartite Alliance functioned as a governing compact: the ANC as the electoral vehicle, COSATU as the organised working-class voice, and the SACP as the ideological conscience of the state.

However, this arrangement also carried risks. As the ANC’s dominance deepened in the early post-apartheid decades, alliance partners increasingly found themselves bound to decisions over which they exercised diminishing control. Policy compromises, particularly in macroeconomic strategy, created longstanding tensions between the ANC leadership and its left-leaning partners.

The ANC’s electoral trajectory over the past two decades provides the immediate context for the SACP’s recalibration. From nearly 70% of the national vote in 2004, the party’s support declined to 57.5% in 2019, before falling sharply in 2024. This erosion was driven by multiple, overlapping crises: persistent unemployment, collapsing municipal services, electricity shortages, and, most damagingly, the revelations of systemic corruption exposed by the Judicial Commission of Inquiry into State Capture.

The Zondo Commission’s findings documented how public institutions were hollowed out, procurement processes corrupted, and state resources diverted for private gain. While these failures occurred under ANC governance, their consequences were borne collectively by alliance partners. For the SACP, continued participation in the Alliance increasingly meant shared accountability without commensurate influence.

The formation of the GNU intensified this rupture. From the SACP’s ideological perspective, governing alongside the DA, a party historically associated with market-oriented policies and opposition to redistributive state intervention, represents a fundamental departure from the alliance’s left-nationalist tradition. While the ANC has framed the GNU as a pragmatic response to electoral reality and constitutional responsibility, the SACP views it as a strategic and ideological compromise too far.

Local government is where these tensions are most acutely felt. Municipalities have become the epicentre of public frustration, marked by service delivery failures, infrastructure decay, and administrative instability. It is also at this level that political accountability is most immediate and visible. By contesting local elections independently, the SACP aims to reassert a distinctly left-wing, working-class political alternative rooted in grassroots mobilisation.

The party has argued that municipalities should be sites of developmental local state practice rather than patronage networks or technocratic management. In this sense, its decision is both defensive, seeking to distance itself from the ANC’s perceived municipal failures, and aspirational, testing whether its historic moral authority can translate into electoral support. Yet the risks are considerable. The SACP has limited experience as an independent electoral actor and lacks the extensive machinery the ANC built over decades.

Fragmentation of the progressive vote could unintentionally benefit opposition parties in closely contested wards. The party’s leadership is acutely aware that symbolic relevance does not automatically translate into ballot success.

Despite appearances, the SACP’s decision does not necessarily signal the end of the Tripartite Alliance. Rather, it reflects a recalibration of relationships under new political conditions. Alliances, particularly those forged in liberation struggles, are not static; they evolve in response to shifting social realities.

For the ANC, the GNU has imposed a new discipline. Governing without a majority requires negotiation, transparency, and demonstrable performance. These pressures, while uncomfortable, may accelerate long-overdue institutional reform and renewal. For the SACP, independent contestation provides an opportunity to rebuild credibility among constituencies that feel politically orphaned.

South Africa’s democracy has entered a more competitive and plural phase. This need not be interpreted solely as decline. Political competition, if responsibly managed, can sharpen accountability and policy clarity. The SACP’s independent participation in local elections may ultimately strengthen the broader progressive project by compelling both parties to reconnect with their social bases and articulate clearer developmental visions.

There remains ample space for strategic cooperation, issue-based alignment, and post-election collaboration at municipal level. The ANC retains unparalleled organisational reach and a historic mandate to govern. The SACP retains intellectual depth, activist credibility, and a long tradition of principled critique. These strengths are not mutually exclusive. If approached with political maturity, the current moment can serve as a reset rather than a rupture, a chance for the ANC to renew its moral authority through performance and reform, and for the SACP to demonstrate relevance in democratic competition.

South Africa’s challenges are too severe for permanent fragmentation of progressive forces. The era of automatic loyalty may indeed be over, but the possibility of principled partnership remains. In a changing political landscape, both the ANC and the SACP still have critical roles to play in shaping a more equitable, accountable, and resilient South African state.

Jerald Vedan

Image: Supplied

Jerald Vedan is an attorney, community leader, and social commentator based in KwaZulu-Natal.

** The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of IOL or Independent Media.

Related Topics: