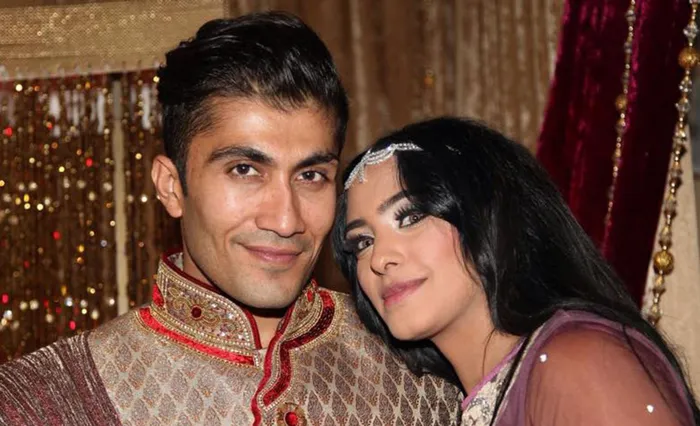

SARBHERA ‘Sarbie’ Amod, 37, of Middelburg, was shot in the head allegedly by her partner, who then turned the gun on himself on January 1.

Image: Supplied

IN 2025, President Cyril Ramaphosa declared gender-based violence (GBV) and femicide a national disaster. The announcement signalled moral urgency and political recognition of a crisis that women in South Africa have lived with for generations. Despite this declaration, the reality on the ground has not shifted in any meaningful way. If anything, the violence has intensified.

According to recent South African Police Service reports, more than 10 000 cases of rape are reported every quarter, while women are killed by intimate partners at a rate several times higher than the global average. These are not new patterns. They are the continuation of a long, violent trajectory that predates the declaration and has persisted despite years of campaigns, task teams, summits, and national conversations.

This forces a difficult but necessary question: what does declaring a national disaster actually change if the underlying conditions remain untouched?

South Africa has spoken about GBV for decades. We mark it during 16 Days of Activism, host annual dialogues, issue policy statements, light buildings in symbolic colours, and reaffirm our collective outrage three or four times a year. The declaration of a national disaster risks becoming just another layer of symbolic recognition unless it disrupts the everyday systems that make violence possible. A new label does not automatically produce new behaviour.

RAMEEZ Patel, 38, was sentenced to life imprisonment by the Limpopo High Court in December for murdering his wife Fatima Choomara Patel, 28, in 2015.

Image: SUPPLIED

A national disaster declaration is not merely a symbolic act. It is an administrative and moral commitment. It signals that the state will suspend routine approaches in favour of urgency, coordination, and measurable action. Without a clearly articulated, well-executed, and publicly accountable intervention plan, such a declaration means very little. In the absence of defined targets, time-bound deliverables, dedicated funding, and transparent reporting mechanisms, the language of disaster risks becomes indistinguishable from the decades of speeches, campaigns, and commemorative events that have failed to stem the violence.

GBV is not an episodic crisis. It is entrenched in the fabric of our society. Treating GBV as a disaster frames it as an emergency event, something sudden and extraordinary. But GBV in South Africa is neither sudden nor exceptional. It is predictable. It is patterned. It is produced through socialisation, economic inequality, power imbalances, and cultural norms that normalise male dominance and female endurance.

Violence thrives not only because of individual perpetrators but also because of collective silence, institutional failure, and embedded beliefs about gender, authority, and entitlement. A disaster declaration that does not challenge these foundations is no more effective than another awareness campaign. If we are serious about change, we must be honest about where it begins. It begins with how we raise our sons and daughters. It starts in homes where boys learn what power looks like and girls learn what is expected of them. It begins with how we excuse aggression as masculinity, obedience as femininity, and silence as strength. By the time violence erupts, the groundwork has often already been laid.

Nazreen Fakier Cajee was brutally stabbed to death in her Johannesburg home three years ago. Her husband, Shaheed Cajee, had been convicted of murder.

Image: Facebook

Schools play a critical role here, yet gender, consent, respect, and emotional literacy remain marginal rather than central to the curriculum. These conversations are often treated as optional, sensitive, or secondary rather than as foundational to citizenship and social responsibility. We cannot expect policing and courts to undo what years of socialisation have entrenched. Prevention is not an add-on. It is an educational imperative. The same applies to how adults interact in everyday life.

GBV is sustained not only through acts of brutality, but through everyday behaviours: jokes that normalise control, communities that look away, families that prioritise reputation over safety, and institutions that discourage women from reporting because the process is humiliating, slow, or futile. When survivors are asked what they did to provoke violence, when neighbours hear screams and do nothing, when workplaces protect reputations instead of people, violence is being socially authorised.

Declaring GBV a national disaster without confronting these realities is not transformation. It is performance.This is not to suggest that policy, policing, and legal reform are unimportant. They are essential. But they are insufficient on their own. You cannot arrest your way out of a cultural crisis. You cannot legislate empathy. You cannot prosecute patriarchy without dismantling the ideas that sustain it. What is missing from our response is sustained, uncomfortable engagement with mindset and behaviour change. Standing up against GBV cannot be seasonal or symbolic. It requires daily courage: calling out harmful behaviour, raising children differently, demanding accountability from institutions, and refusing to normalise violence in private spaces.

It requires men, in particular, to see themselves not as distant supporters of a women’s issue, but as active participants in dismantling the systems that benefit them. A society does not become violent overnight, nor does it become just overnight either. Declaring gender-based violence a national disaster was a necessary acknowledgement. But acknowledgement without disruption changes very little. Until South Africa is willing to confront the cultural and social foundations of violence, declarations will remain words layered onto wounds.

GBV is not only a criminal justice failure. It is a social one. And until we change the way we think, raise our children, educate our communities, and hold one another accountable, the statistics will continue to rise, no matter how many times we declare our outrage.

Professor Aradhana Ramnund-Mansingh

Image: File

Professor Aradhana Ramnund-Mansingh is the manager, School of Business, Mancosa; empowerment coach for women and former HR executive.

** The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of IOL or Independent Media.

Related Topics: