KZN's matric pass rate raises questions of quality and sustainability

Significant achievement

KZN’s 90.6% is not luck. It looks like the output of a system that has learned how to run a feedback loop, says the writer.

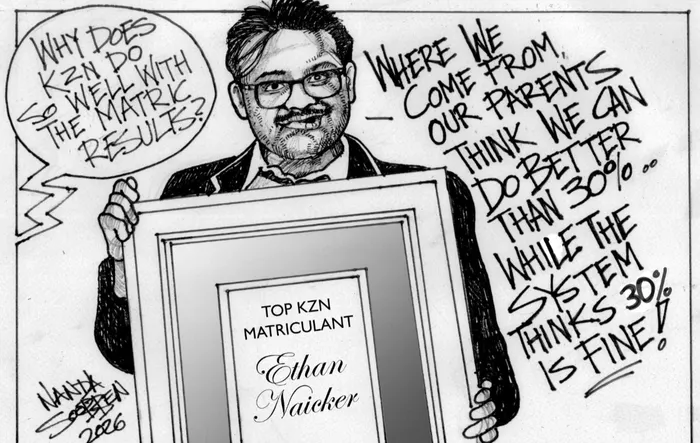

Image: Nanda Soobben

As KZN celebrates this significant achievement, the need for long-term solutions looms larger than ever, writes PROFESSOR WAYNE HUGO.

KWAZULU-NATAL'S 2025 matric pass rate landed at the top of the provinces at 90.6% and I had two reactions fighting inside my head.

One was the knee-jerk suspicion: how does KZN beat the Western Cape and Gauteng? Something must have been cooked. The other was the slower, research-trained voice: KZN has, for several years now, been running a fairly serious improvement machine, with repeated reports that it is doing what it says it is doing.

The suspicion is not irrational. Many of my now-qualified students cannot find teaching posts without some kind of informal “fee”.

They are doing Honours and Master’s programmes because they can’t find a teaching post.

On school visits principals tell me they do not have money for cleaning products, never mind ink and paper. And everyone inside education knows the province’s finances have been strained to breaking point.

So the question is not whether cynicism is allowed.

The question is whether cynicism explains this result. The cleanest way to start is with the pattern, not the mood.

KZN did not jump once. The pass rate rose year after year, from 76.8% in 2021 to 90.6% in 2025. And the province did not get there by shrinking the number of candidates writing matric.

In 2025, 171 368 candidates wrote and 155 258 passed.

That is a large cohort and a record pass rate at the same time. If you want to build a conspiracy that the numbers were managed, you have to explain why the system would choose the hardest route: a bigger exam and more passes while still lifting the percentage.

That does not mean there is no politics in education. It means the simplest conspiratorial story, that they just kept weak pupils out and pushed the rate up, does not do much explanatory work here. Something else has been going on. There could be national-level manipulation that somehow KZN benefited from, given its poverty profile, but I don’t have any proof of this. What I do have is some insight into how KZN has, over the last few years, built a feedback system that actually functions. Not perfectly. Not everywhere. But enough to shift the curve.

By this I mean a very practical sequence: measure early enough, identify the real mistakes, intervene in time, and improve teaching capacity so that the same mistakes do not return in the next cohort. First, the province improved the way it diagnoses learning problems.

Schools have always had tests. The change is what is done with them. If assessment data is looked at topic by topic, and if it is used to see patterns of error rather than just produce marks, then it becomes a tool for action rather than a formality.

A good diagnostic system tells you, in June, what will sink you in October. Second, it built targeted support around that diagnosis. Subject camps and extra tuition are not new in South Africa.

What matters is whether they are generic revision sessions or whether they are aimed at the specific gaps the diagnostic work revealed. Extra time on task only matters when it is aimed at the right thing. This is where error analysis counts. If pupils repeatedly lose marks because they cannot translate a word problem into an equation, or because they make the same substitution error in physical science, then the intervention has a clear target. Without that link, camps become noise.

Third, it treated teacher capability as something you build cumulatively. Real improvement depends on teachers deepening their grasp of the same topics year after year, and building stable routines for teaching them. Senior markers returning from matric marking told me, with both pride and surprise, that the teachers marking this year showed stronger subject knowledge and more consistent marking. The relative stability of CAPS since 2012 has certainly helped here.

The main point is that these three pieces feed each other. I love feedback loops and this one is clear. Error diagnosis makes support more targeted. Solid support prevents a cohort from being lost while the slower work of improving teaching takes effect. Improved teaching makes support better, because the camps are staffed by the same teachers who are teaching in ordinary time. Once that loop runs for a few years, you start to see compounding. Not miracles. Just fewer wasted hours, fewer repeated mistakes, and teachers who are less improvisational because they have better routines and stronger content knowledge.

I am not saying that teachers are giving high quality feedback in their classes across the province, our research indicates very strongly they are not. In class quality feedback is a high level, time expensive, skill that is in short supply across our schools, but our intervention programmes and policies are pushing in this direction. There is a second signal that points in the same direction.

The national School Performance Report shows that in 2025, 1 526 of KZN’s 1 764 schools were in the 80 to 100% band, with 313 schools at 100%. If most schools are sitting in a high band, then improvement is not limited to a few showcase schools. The curve has shifted across the province. But it’s not all champagne and celebration, even if this has been freely flowing across principals’ and district officials’ desks over the last couple of days.

KZN has raised the floor faster than it has raised the ceiling. In gateway subjects, KZN’s own reporting shows a familiar pattern. Large proportions pass at 30%, but far fewer reach 50% and above. Physical Science has 77.9% passing at 30%, but only 29.7% at 50%+. Technical Science shows 97.1% at 30% and 31.4% at 50%+. That means the system is getting better at pushing pupils over the minimum threshold, but it is not yet producing deep mastery at scale. This insight holds even though we have improved our bachelor level passes.

If KZN wants more engineers, artisans, technicians, and health professionals, the ceiling matters. You do not build a technical economy on borderline passes. This is why the minister’s national warning is not irrelevant: mathematics and accounting performance dropped nationally, and the next phase has to be deeper mastery, not only more passes. This is also where the teacher supply issue matters, even if it is not the headline. We can talk about depth all we like, but depth depends on specialist teaching.

KZN, like much of the system, has mismatches: relative oversupply in some Intermediate and Senior Phase posts, and more pressure in Foundation Phase and in FET specialist areas. Foundation Phase is where the numeracy and literacy bases are built. FET is where deep subject teaching either happens or does not. If KZN wants the next jump, it will not get there mainly through camps. It will get there through getting specialist teaching right. UKZN is already playing a significant role here, but serious investment is needed - high-level skills are not cheap.

The second big risk is sustainability. Ink and paper shortages are not a minor inconvenience in a system that relies on routine assessment and targeted remediation. When advisors and managers are fighting for petrol money, school visits drop, and diagnosis weakens. And once diagnosis weakens, everything downstream loses its bite. The danger is how delays work in schools. Systems do not collapse the moment stationery runs out.

First, assessment routines thin out. Then the data becomes less usable. Then interventions lose precision. Then teacher development becomes crisis management. The results drift downwards, and everyone shouts “corruption” while forgetting the small manyana failures that started it. And then, for me as a university professor, there is the post-school bottleneck.

KZN’s bachelor passes rose from 61 856 in 2021 (37.1%) to 89 161 in 2025 (52.0%). This is not a small shift. It means more pupils are now university eligible. But universities are already at capacity. Residences are oversubscribed. Funding is contested. UKZN can take just under 10 000 new students, but had around 300 000 applicants. You do the math. If the schooling system produces more success without the post-school system expanding, then we create a new kind of failure: pupils do what they are told, and then hit a closed gate — and when young bright students find their promised futures shut down.

So my own conclusion is that KZN’s 90.6% is not luck. It looks like the output of a system that has learned how to run a feedback loop. The personal anecdotes from matric marking fit that story, and the multi-year trend fits it too. But 2026 has started with many schools crying out for printing, stationery, cleaning materials, transport, and stable staffing. Without money and support the feedback loop weakens and the gains stop compounding.

And if post-school places do not expand, the province will be producing success that turns into frustration and revolution. That said, the gains are real and they came from somewhere: thousands of teachers and hundreds of thousands of learners working extra hours, weekends, holidays doing the unglamorous work that actually compounds.

Professor Wayne Hugo

Image: Supplied

Professor Wayne Hugo teaches at UKZN's School of Education with a strong interest in how to use education as a mechanism to improve our world.

** The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of IOL or Independent Media.