Each year, a new study is announced with great urgency; each year, a crisis is declared, as if for the first time. Yet if we pay close attention to the decades-long patterns of schooling in this country, we notice that this is not news, says the writer.

Image: Meta AI

THERE are moments in public discourse that echo inside a cave, a sound so repeated and unexamined that it begins to feel like revelation simply because it is familiar. The annual lament about the decline of mathematics and physical science in South Africa is one such echo. Each year, a new study is announced with great urgency; each year, a crisis is declared, as if for the first time. Yet if we pay close attention to the decades-long patterns of schooling in this country, we notice that this is not news.

The problem with the echoing noise is not that the warnings are entirely wrong. The difficulty is that this noise continues to arise from a vantage point that can see only deficit and never possibility, a vantage point I shall call – borrowing the language of metaphor – “the Western mirror”.

In this mirror, South African pupils appear as faded reflections of an ideal norm; pupils who should have mastered early numeracy, experienced coherent teaching, and progressed through schools that function like those in affluent parts of the world. But this mirror hides more than it reveals.

Minister of Basic Education, Siviwe Gwarube, in her speech announcing the 2025 matric results, was unafraid to address public pressure to improve the country’s educational outcomes.

“People ask about ‘quick wins’,” she said.

“But real reform in a system this size cannot be PR-led. It is deep work that succeeds only when leadership lines up resources, accountability, trust and data behind one clear direction: strengthening the foundations of learning.”

The minister noted that the National Education and Training Council (NETC), established in 2025, was now reviewing assessment and progression policies across grades R to 12 to ensure that expectations are clear, support is provided earlier, and learning gaps do not compound by the time learners reach matric. Those who speak of a decline in participation in mathematics and the physical sciences usually begin their account in a very recent year.

They report that the number of pupils taking core mathematics has fluctuated over several examination cycles, and they urge us to be alarmed. If we remain within the Western mirror, we compare ourselves to international benchmarks and find only disappointment. If we step outside it, another picture comes into view.

According to the Institute of Race Relations, the overall matric pass rate in 1993 was approximately 37%, one of the lowest in South Africa’s educational history. In the same year, the university entrance pass rate, then known as endorsement, dropped to about 8%. Detailed subject-level pass rates for mathematics from this period are not widely available in publicly accessible digital form. Statistical reporting in the early 1990s was limited and uneven, and records are often preserved only in print archives.

However, given the extremely low overall pass and endorsement rates, mathematics performance during this period was generally very poor, with many pupils failing outright or achieving very low marks. In 1980, the overall matric pass rate stood at approximately 53.2%, yet success was sharply stratified by race. Black African pupils achieved extremely low success rates in mathematics and in endorsement passes compared with their white counterparts. From this historical vantage point, the years since democracy have not seen a fall from a golden age but a long, uneven effort to widen the gate.

Curriculum reforms, from Curriculum 2005 through successive revisions to the present CAPS framework, were not merely technical adjustments. These efforts to transform mathematics and science from elite subjects for a few into gateway subjects for the many. In the process, the curriculum was softened in places and then strengthened again. Euclidean Geometry was removed from the compulsory core, offered as an optional paper, and later reinstated as a compulsory core subject. The final examination has gradually become more demanding.

In the 2025 National Senior Certificate examinations, 254 415 pupils sat for mathematics, one of the most demanding subjects in the curriculum. Of these, 162 947 achieved 30% or more, resulting in a national mathematics pass rate of 64.0%. This figure has dominated public debate, often cited as proof that mathematics remains the system’s greatest weakness.

Provincial and district-level data, however, show wide variation in performance, with several districts consistently achieving results well above national averages, often with large cohorts of pupils. At the school level, hundreds of public schools record pass rates between 80% and 100%, despite operating within standard staffing norms, curriculum requirements, and accountability conditions. During the same examination cycle, 345 857 pupils achieved Bachelor-level passes, the highest number ever recorded. Official results confirm that the majority of these passes were achieved by pupils from Quintiles 1 to 3 and no-fee schools.

This leads us to a more honest question. Are we witnessing a decline from an imagined past in which everyone did advanced mathematics, or are we seeing the predictable tension that arises when a system attempts to deliver rigorous content to a far larger and more diverse cohort than it ever intended to serve? The Western mirror has another favourite image: the pupil who flees from core mathematics to mathematical literacy. The image is vivid, yet misleading. It assumes that mathematical literacy was designed as a soft landing for those who could not cope with “real” mathematics, and that its primary effect is to close doors to high-status careers.

What is rarely discussed is why mathematical literacy was introduced in the first place. For decades, the system produced school leavers who could manipulate algebraic expressions yet could not interpret a payslip, compare loan offers, read a graph in a newspaper, or make sense of the numbers that shape civic and economic life. None of this denies that subject choice is often painful. But subject choice does not occur in a vacuum. It is shaped by the presence or absence of qualified teachers, by class sizes that make individual support impossible, by years in which learners sat without a mathematics teacher, and by schools where physical science appears on the timetable but not in practice.

The crisis story usually ends with familiar remedies: more resources, better training, and more mentoring. All are necessary, but none are sufficient. They fail to capture the deeper pattern that the national conversation repeatedly misses, the pattern that the Western mirror cannot reflect. If we changed the mirror, we might change the message. Instead of repeating a single story of decline, we could tell a more complex one: a story of deep inequality coexisting with remarkable acts of learning and teaching under constraint. That story would not excuse mediocrity. It would invite policy grounded in reality rather than in imported ideals.

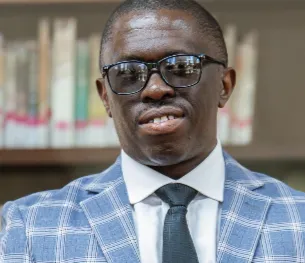

Dumisani Tshabalala

Image: Supplied

Dumisani Tshabalala is the Head of Academics at the Oprah Winfrey Leadership Academy for Girls (OWLAG)

** The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of IOL or Independent Media.

Related Topics: