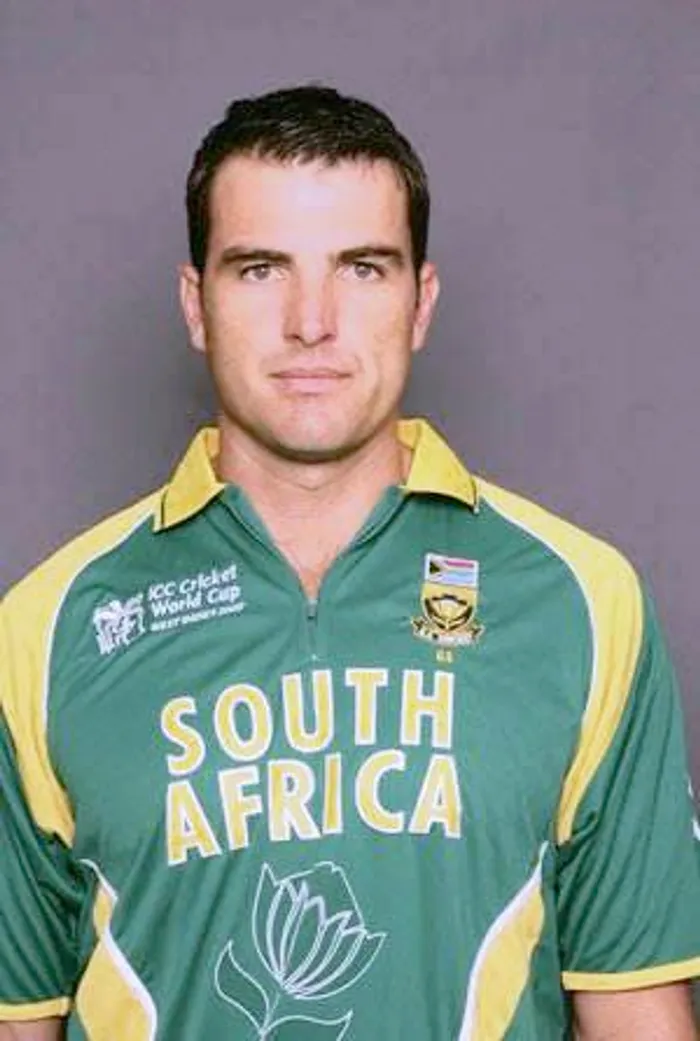

Justin Kemp Justin Kemp

Retired Proteas cricketer Justin Kemp was ruled not out after an urgent High Court application to interdict him from competing with his ex-business partner.

The application, by Big Catch Fishing Tackle (Pty) Ltd and Hout Bay businessman David Christie and his co-applicants, was dismissed with costs in favour of Kemp and his co-respondents. They include Big Catch colleague Richard Wale who is now a co-director in Kemp’s new venture Upstream Fly Fishing CC.

Last week’s ruling comes against the background of an ugly legal battle raging since March 2018 when Christie accused his then co-director Kemp of running his own “shadow” business on the sideline and siphoning off commissions from exclusive fishing charters he thought were being hosted to promote the Big Catch brand.

That legal battle will be played out, probably only next year, when Christie and Big Catch attempt to sue Kemp for nearly R3,7 million for past damages and just over R20 million in future damages.

The hefty claim is based on allegations of misappropriation of fishing and fly fishing tackle, equipment and apparel; unauthorised direct payments of commission income to Kemp; unaccounted sales of stock at discounted rates; reckless transactions and payment to customers; unauthorised donations and sponsorships; and future loss of profits.

The commission income relates to charters to destinations like the Seychelles atoll Alphonse Island, one of the most exclusive salt water fly fishing destinations.

On average a charter including accommodation in a luxury boutique hotel and flights costs a fisherman R150 000 a week.

Alphonse concession owners paid charter hosts like Big Catch about $1000 US per fisherman.

Kemp denies all allegations, noted acting High Court Judge Johan De Waal in his judgment last week.

“His version is that he approached Christie during February 2018 to tell him that the company could no longer afford substantial salaries for both of them and that one of them must buy the other out.

“When Kemp did not accept Christie’s offer for his 50% shareholding, the latter accused him of all sorts of wrongdoing. Under duress and coercion caused inter alia by the laying of criminal charges against him, Kemp decided to resign.”

Disagreeing with Christie’s argument that Kemp was still bound by his fiduciary duties, De Waal, quoting a variety of case law, noted the default position changed on resignation.

“This must be correct,” continued De Waal, “because otherwise a director or senior employee would effectively have to change careers every time he leaves a company. I say this because the position contended for by the applicants (Christie) would mean that the director or employee would not be able to continue working in the same line of business after leaving his company.

“That cannot be right. If that was the general principle, there would be no need for restraints of trade and the extensive jurisprudence developed by our courts in order to ascertain whether such restraints are reasonable.

“I agree with the respondents’ (Kemp’s) submissions that whilst the fiduciary duties of a director and employee survive the termination of the relationship with a company the duty will only be breached after resignation if it involves the use of confidential information or violates an interest of the company that is worthy of protection in some other way.”

Quoting a Supreme Court of Appeal (SCA) judgment, De Waal also noted that it must be “emphasised that the expertise and experience acquired by a director during his period of employment with the company and in general even the personal relationship established by him during that period belong to him and not to the company.

“The SCA also referred, in this regard, to section 22 of the Bill of Rights and the principle that all persons should in the interests of society be productive and be permitted to engage in trade and commerce with their professions without undue restraints on post-resignation activities.

“This, in my view, can only mean that a company that wishes to prevent a director or employee from competing with it after resignation should either do so by way of imposing a reasonable restraint of trade or it will have to persuade a court that it has an interest worthy of protection, such as confidential information, client lists or connections, that justifies an interdict.”

“In this regard, counsel for the respondents, correctly in my view, contended that, in the absence of a restraint of trade, the onus shifts to the director’s former company to justify the interdict both in law and in fact.”

Christie did not satisfy this onus, concluded De Waal. “I do not believe that a proper case was made out for interim interdictory relief.”

In dismissing the entire application, De Waal also commented that Christie could not point to a single trip by Kemp in the future which amounted to a business opportunity to Big Catch while Kemp was a director.